George Herms at “Earful,” a Tap City Circus raffle in Los Angeles, 1972. The Getty Research Institute, Gift of George Herms, 2009.M.20.24. Photo by and © Jerry Maybrook

George Herms is known for his poetic assemblages of discarded, disheveled materials. But back in the ’60s, he had preoccupations besides art: he was “tapped out”—that is, broke and ready to tap-dance on street corners for cash—and facing eviction.

His solution? “Tap City Circus,” a carnivalesque fundraiser that was equal parts auction, picnic, and performance. Herms called it “the highest example of using life’s pitfalls as a springboard.”

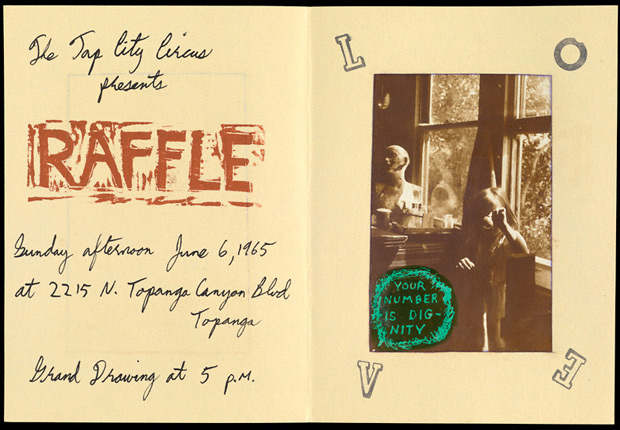

The first raffle, held in 1961 in Larkspur, California, was such a success that Herms staged it every 18 months or so until 1972. Each event had a special name. Lucky invitees to the 1965 “Raffle,” Herms’s first Tap City Circus at his new home in Topanga Canyon, received colorful, hand-printed invitations stamped “L-O-V-E.” You can see one in the Pacific Standard Time exhibition Greetings from L.A.: Artists and Publics, 1950–1980, opening this Saturday at the Getty Research Institute.

Announcement for “Raffle,” a Tap City Circus raffle in Los Angeles, June 6, 1965. Designed by George Herms. Letterpress, woodblock, rubber stamping, and tinted gelatin silver print. The Getty Research Institute, Gift of Rolf G. Nelson, 2010.M.38.4

After “Raffle” came “Roofle.” Another was dubbed “Earful.” Prizewinners at the “Waffle” event received a “wall full of effluvia.” (Hear more of the story, and learn about Herms’s mail art, in this video interview with the artist and curator John Tain.)

Raffle tickets, which cost $1, were small numbered cards decorated with poetry or imagery that could also be taken home as souvenirs. Prizes were books or prints. But lucky winners could also opt, as an alternative, to squirt Herms with a hose. And the Grand Prize winner could take home one of the artworks on display in Herms’s house. Tap City Circuses were social gatherings, too. Local artists came to picnic and stage impromptu musical performances.

Ironically, all this industrious work, from the raffles to the elaborate printed cards, required more time and effort than Herms could possibly have recouped in raffle funds. The event’s fusion of childish antics, disciplined craft, and seeming indifference to life’s practicalities was, in the end, an art piece of its own.

Adapted from a sidebar written by Nancy Perloff. Read more about Tap City Circuses in the new book Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles Art, 1945–1980.

Comments on this post are now closed.