Portrait of James Christie, 1778, Thomas Gainsborough. Oil on canvas, 50 1/4 x 40 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of J. Paul Getty, 70.PA.16

The stock and sales books of the art dealers M. Knoedler & Co. provide a who’s who of American art collectors, but J. Paul Getty is notably absent from the firm’s financial ledgers. Did the gallery include the prominent collector among its customers? Knoedler’s correspondence reveals information about the dealer’s relationship with Getty.

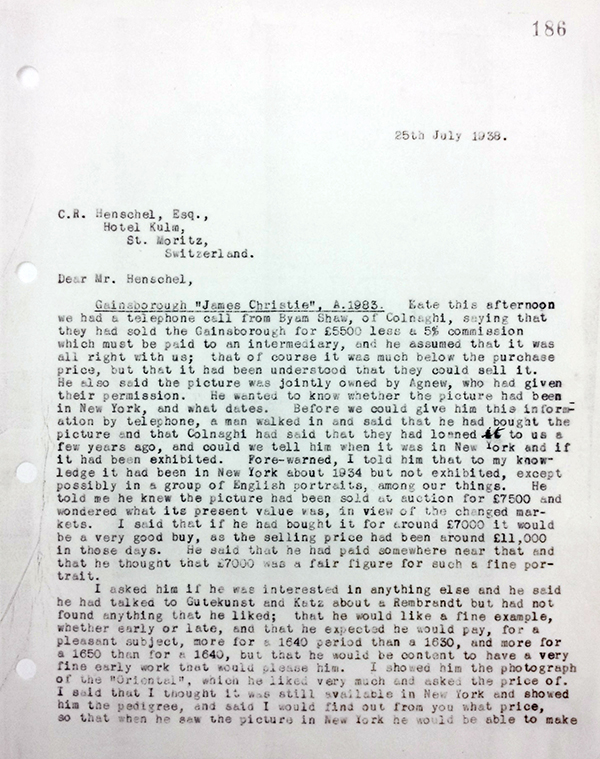

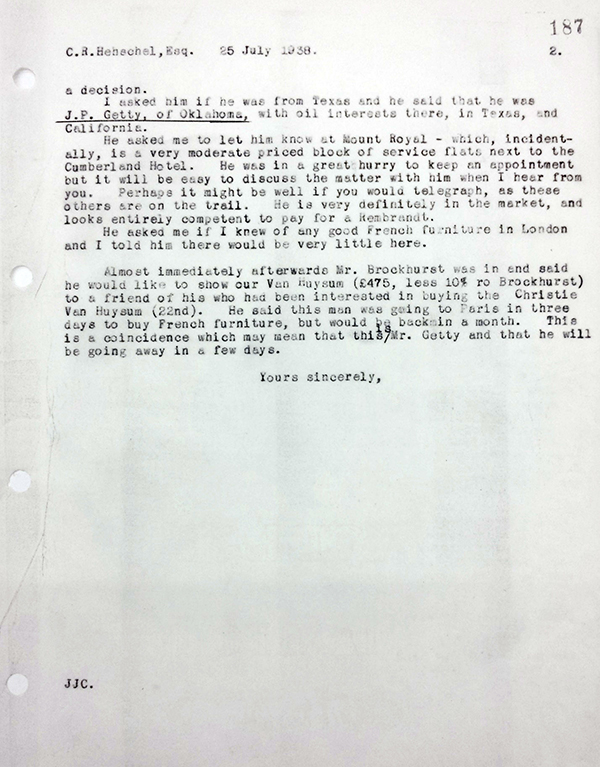

The First Encounter

The earliest mention of the collector in the firm’s correspondence may be a letter dating from the summer of 1938. It refers to what appears to be the firm’s first encounter with J. Paul Getty, which would have taken place sometime late in the afternoon of Monday July 25, 1938. That encounter did not take place at the firm’s New York office, but at the firm’s gallery in London. In the letter written by John J. Cunningham to Charles Henschel on the day of the encounter, Cunningham describes how a man visited the gallery that afternoon to inquire about Thomas Gainsborough’s painting Portrait of James Christie (1778). The man had just purchased the painting from P. & D. Colnaghi & Co.

M. Knoedler & Co. was familiar with that work, as it had been a joint acquisition between Colnaghi, Agnew, and Knoedler. That very afternoon, Colnaghi and Knoedler had actually spoken on the phone to discuss the painting’s history and to clarify when the painting had been at the Knoedler’s New York gallery. During this brief first encounter with the new owner of Portrait of James Christie, the Knoedler firm learned two basic facts about this man: his name—Getty—and his profession in the oil business.

Who was this man named Getty? Intrigued, Cunningham wrote to Williams J. Collins of the New York office on August 12 to inquire whether he had any information on “this man named J. P. Getty.” In a letter dated August 23, 1938, the New York staff reported that they had “nothing definite” on Getty, having “only learned about him 5 weeks ago.” They noted though: “he has plenty of money and [is] spending it on fine furniture and pictures.”

Letter from J. J. Cunningham in London to C. R. Henschel detailing his first encounter with J. Paul Getty and the collector’s interest in acquiring a Rembrandt painting. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.M.54

Letter from J. J. Cunningham in London to W. J. Collins in New York detailing the gallery’s first encounter with J. Paul Getty, “an oil man from Texas and Oklahoma, as well as Southern California.” The Getty Research Institute, 2012.M.54

Hunting for Rembrandts

Knoedler staff learned that Getty was in contact with the art dealers Gutekunst and Katz about acquiring a “very fine early work” by Rembrandt, but he had yet to find anything to his liking. Cunningham describes him as “definitely in the market, and looks entirely competent to pay for a Rembrandt.”

Subsequent letters between the London and Paris offices document Knoedler’s hunt for a Rembrandt painting to sell to Getty. Within a few weeks, Knoedler identified three possible artworks, including one in New York available for him to see. The gallery still had no significant information about Getty, and his frequent travels made him difficult to contact. An interoffice letter between London and Paris dated September 19, 1938, voices concerns that “he will no doubt go straight into the arms of P. & D. C. [Colnaghi], so we would like to have something intriguing to hold him off until he arrives in America.” The writer also shares a rumor: other dealers encountered difficulties getting this collector to pay his bills. Colnaghi could not get ahold of Getty for the payment of Gainsborough’s Portrait of James Christie.

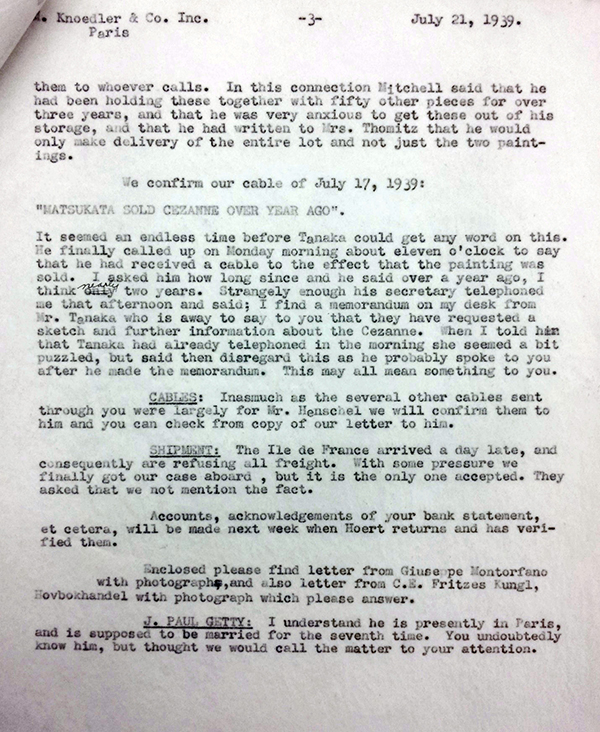

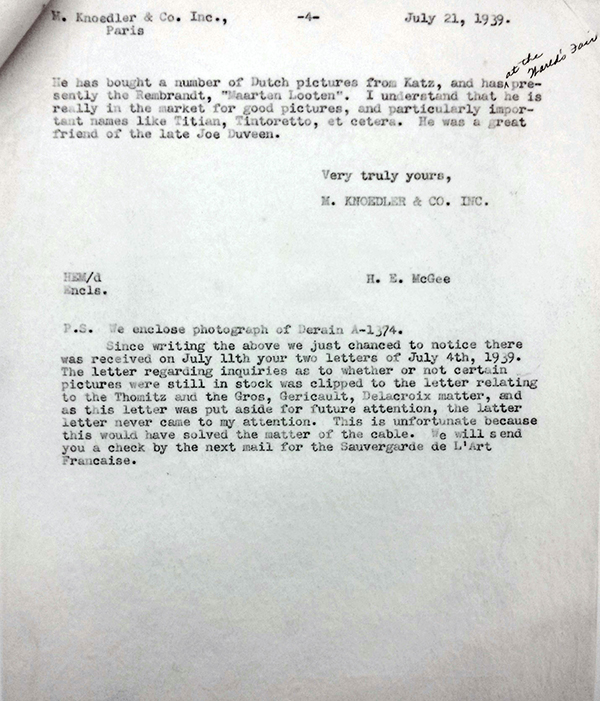

Getty’s name appears again in a letter dated July 21, 1939, in which the New York office states that Getty is in Paris and married for “the seventh time” (it was actually his fifth marriage). The writer reveals that Getty finally has a Rembrandt in his possession—the Portrait of Marten Looten from 1632. Knoedler feared the sale had proceeded through Colnaghi, but the transaction had been brokered through another dealer.

Letter from the New York office to the Paris office confirming that J. Paul Getty is in possession of Rembrandt’s Portrait of Marten Looten. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.M.54

Portrait of Marten Looten, 1632, Rembrandt van Rijn. Oil on wood, 36 1/2 x 30 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art

A Missed Opportunity?

Subsequent mentions of the collector in the correspondence records are extremely brief. One letter from November 9, 1950, merely states that Getty dined with Mr. Messmore but had “so far bought nothing.”

Can we venture from these few documents the reasons for the missed opportunity? Getty’s interest in fine furniture was outside of the area of expertise of M. Knoedler & Co. The firm’s high level of efficiency and its high volume of sales were perhaps less compatible with the chasing of a collector with a busy traveling schedule, hurdles that may have been perceived as less of a difficulty for Joseph Duveen who had been fond of providing a highly personalized service to his clients. The painting that Knoedler’s staff had offered for sale to J. Paul Getty on his first visit to the London gallery was in storage at the firm’s main office in New York. J. Paul Getty may have been drawn to dealers whose main offices were in London, Paris or other European cities.

Gainsborough’s Portrait of James Christie is part of the permanent collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum. As for the Rembrandt, additional information about The Portrait of Marten Looten is available in the Getty Research Institute’s Duveen Brothers archive, which is newly available online. In 1953 Getty donated the painting to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it remains on view to this day.

The records of the art dealers M. Knoedler & Co. contain more information about this story and many other interesting episodes in the history of the American art market. The large and complex Series VI. Correspondence (1,626 boxes!) was processed in partnership with the National Endowment for the Humanities. With the finding aid accessible online, these stories await discovery by scholars.

_______

The Knoedler archive is available for study by qualified researchers. To consult online selected digitized portions of the archive, including stock books, sales books and letters, visit the Getty Research Institute’s online search page. For an update on the cataloging of the archive, see the archive’s information page.

For further provenance information relating to purchases of paintings by the Knoedler Gallery, search the database of the Provenance Index. Works and other archives pertaining to the art dealer M. Knoedler & Co. from other institutions, including the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, the Archives of American Art, Harvard, and the New York Public Library, may be found in the online database of the Digital Public Library of America.

See all posts in this series »

Very cool and very Interesting!