Linsey Davis enjoying the Mediterranean climes of the Getty Villa

Novelist Lindsey Davis has devoted her career to entertaining readers with zesty whodunits set in ancient Rome. Famed for her ability to evoke ancient life down to its sounds and smells, as well as for her clever plots full of memorable characters, crimes, scandals, and romance, Davis turns out to be a bit of an accidental classicist.

She spoke about her work, and the leaps of faith that helped her quit her office job and pursue a fiction career, at the Getty Villa earlier this summer (an excerpt is below). Before the talk, she sat down with me to discuss writing and the ancient world.

What drew you to the Roman Empire?

I wanted to write about England in the 17th century, but nobody would buy what I was writing. At the end of the 1980s, I asked myself, “What do I know about, and what is my interest that nobody’s writing about?” Today when you go into a bookshop, every other book is a Roman popular novel, but in those days there were none. I set out to do something completely original to me.

What caused you to continue with the Romans, once you’d started?

They sold! I’m a professional author; I write to earn my living. When there was something I could do that would achieve that aim, I did it. If you’d told me then that I’d be writing about the Romans for over 20 years, I would’ve been surprised and perhaps slightly perturbed. But it’s been great fun.

What aspects of Rome particularly appeal to you?

The things I find appealing are, first of all, the weather, and then the Roman street life.

The reason I prefer the Romans to the Greeks is that the Romans were, in my opinion, good to their women. When a Greek went out to dinner, he left his wife at home in the women’s quarters; when a Roman went out to dinner, he took his wife with him. That’s a very appealing aspect of their society.

You evoke some aspects of Roman life that are troubling or violent. Are there some sides of ancient Rome that you feel uncomfortably close to?

I think part of my job is to show how the Romans were the same as us as human beings. On the whole, that’s fairly easy to do, but I’m also a historical novelist, and my job is to show where they were different. The two main areas were their acceptance of gladiating and slavery—and I do find both uncomfortable. I’ve written a book about the gladiatorial scene, and I did not enjoy it. I find slavery more interesting because, to some extent, it’s more ambiguous—the idea that slaves were part of the Roman familia.

Slaves prepare dinner on this wall fragment (Roman, A.D. 50–75. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 79.AG.112). Davis says, “I don’t only deal with where the rich live, I deal with the people on the streets and in the kitchens, and cleaning the lavatory—all of them.”

You were a civil servant in England before embarking on your writing career. Was that good preparation for writing about the Romans, who were also quite bureaucratic?

Strangely, it was. When I left university, I had to get a job, and I didn’t think you could be a writer. I thought you couldn’t earn your living that way. Most people still can’t, in fact. I feel that to be a successful novelist, you have to have lived first. So I did get a proper job, and, therefore, I can write about people who have to get up and go to work. I was a civil servant in what had been the Ministry of Works for 13 years, and I did a variety of jobs. When I write about Roman bureaucracy, especially when I’m satirical about it, I know what I’m talking about!

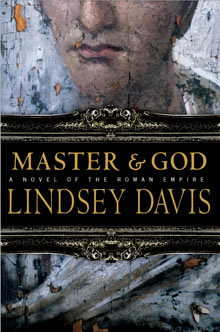

In your latest novel, Master and God, you move forward in time about 10 years from your earlier novels, progressing from emperor Vespasian to Domitian. Why did you choose to do that?

For simple commercial reasons, to some extent. My editor had moved to a different publisher, and I was in the mood to write something completely different, but they wanted something that would be recognizably a Lindsey Davis novel. So I agreed to write on a Roman subject. I didn’t want to write another Falco novel because I had written 20, so I really was Falco’d out. I wondered if I could do a straight historical novel like The Course of Honour, which is about Vespasian and his mistress Antonia Caenis.

I never thought I’d want to write about Emperor Domitian, because he was so horrible, paranoid, and cruel, but I did think there were a lot of very exciting events of all sorts: a war, events at home in Rome, and him going barking mad. Then there’s his extraordinary assassination, which was partly organized by civil servants. I think my starting point was the assassination. Once I’d fallen upon that and found there were lots of scenes I could make use of with other characters, without writing about him directly, it all fell into place. I enjoyed it hugely.

On your website, you say you don’t want to write about the eruption of Vesuvius—which, as it happens, is the subject of an exhibition at the Getty Villa this September. Why not?

What I mean by that is very specific: I mean that describing what happened has been done so well by Pliny. The only thing we don’t know, in my opinion, is about the pyroclastic flow. He didn’t know or understand that, and that’s one of the things archaeology is still discovering.

To write a Falco novel, that sort of light novel, I’ve always thought would be deeply inappropriate [to set it against the eruption of Vesuvius] because it was a massive, catastrophic tragedy. The thing that brought it home to me was the tsunami in the Far East. I thought of the extraordinary results of this, the impact it had on everybody—I knew someone indirectly who was never found. That made me realize that I definitely can’t do this. Besides, other novelists have done it; I like to do things that are all my own.

You mentioned Pliny. Are there other Roman authors you’d recommend for readers who want to learn more about life in Roman times?

My favorites are the satirists, because they give you such a colorful view of life and in a humorous, scathing way, which appeals to me.

Is there anything that you wish people would ask but never do?

People always ask about the history, and my subject was English language and literature, and I would be quite interested in being asked about the craft of writing. I do think the reason people like my books is not just for the history, but for the fact that they may be very well written! But they never do.

I’ll ask about the craft! Tell us what you’ve learned about writing over the course of your career.

That no matter how hard you try, someone will always complain! Having said that, there are many people who will just simply be pleased by what I’ve done, and it’s for them that I write, to give them pleasure, to give them relief from their troubles, and—not to be didactic—to expand their horizons a little bit.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.