Harry Gesner has built some of Modernism’s most unorthodox houses. This includes the Scantlin House at the Getty Center, which Getty architect Richard Meier insisted on preserving as the Center was being constructed and is now used by the Getty for special events.

Gesner will be the guest of honor and a speaker at the Iconic Houses Network for its annual conference February 17–19, 2016, at the Getty Center. Sandcastle House, his private residence, will also be toured by conference participants.

We spoke with Gesner about his architectural legacy and his current and future architectural plans.

Where did your interest in building houses originate?

It began when I was a kid, delivering papers in L.A. In those days, a lot of new houses were being built on my round, including many interesting ones. I’d walk in and have a look them. I always wanted to be an architect; I just had an intuition that it would be a fun thing to do. This was even though my uncle, an architect—unlicensed although he was very good—told me I didn’t have enough talent. Of course, telling me that just made me want to do it even more. I was always drawing houses, even then. That’s really why I never wanted to study architecture; I’d always felt one jump ahead.

So how did you get into the profession?

After the war, I worked as a television cartoonist in New York, but I’d take the train to Yale to listen in on the lectures of Frank Lloyd Wright. He ended up inviting me to join him at Taliesin West, but that wasn’t for me. If I’d done it, I’d just have ended up being a paler version of Frank Lloyd Wright. Instead, I decided to give myself ten years to teach myself to be an architect. I’d pick a construction site that looked interesting, and I’d ask to work there as an apprentice. I was a carpenter, stonemason, or anything else I could get into. I only picked exceptional houses. That’s how I learned. As an architect, I believe you should always be able to construct the buildings you design. I always work on my own houses.

To say you’ve led an interesting life would be a huge understatement. What’s the link between your many adventures and your work?

While I was fighting in World War II, I always said to myself, and to anyone who might be listening, “If I survive this, I’m going to do something important with my life.” On my travels, I learned to appreciate fine architecture. When I was in Europe during World War II, whenever I could I’d explore a castle. Castles are hands-on architecture. The masons designed and built them, from the intricate knowledge that they had in their heads. You don’t find plans for medieval castles. Seeing them made me think more about the fine points of designing a habitat, and what stuck in my head was that these were autonomous structures. I try to design autonomous houses that function.

Do you have a favorite house among the many you have built?

It’s the one I am working on. Even though I’ve designed over 100 houses over the years, my favorite is always the current one. I just started the Keep House—a series of domes and a keep for an engineer and a writer and their kids. It’s on a 10-acre site, between the mountains and the ocean.

How do you go about designing a house?

The way I design is to go to the site and sit there for hours at a time. I return to it again and again at different times. With my design I follow the contours of the Earth. It’s a very individual approach, and each of my house solutions only applies to that particular site. I don’t have any formulas. I design to nature, taking account of the sun and wind. Nature is my teacher, rather than other architecture. I don’t study other people’s work.

Apart from the new house, what else are you currently working on?

There’s the Autonomous Tent, which doesn’t depend on formal foundations and can be put up in a few days. It doesn’t even require you to level the land, so it doesn’t destroy its natural contours. Although it’s informal architecture, it will easily last 100 years. Another autonomous housing project is the Mushroom House, a tripod house above the ground—I think we have to get back into the trees! Then Kelly Slater, the great surfer, has this project called The Perfect Wave—an engineered artificial wave that will be a quarter of a mile long, which he has been developing for 12 years. He has contacted me to master plan the project.

Do you still surf?

I did until quite recently, but I’ve stopped now. I’m 90, and it’s OK to let go of certain things.

You’re known for your houses on “unbuildable” sites, like the Cahuenga Pass Boathouses. Is there any site that can’t be used?

No. I can solve every problem. I love a challenge. Most of my houses are on difficult sites—I have no problems with problems!

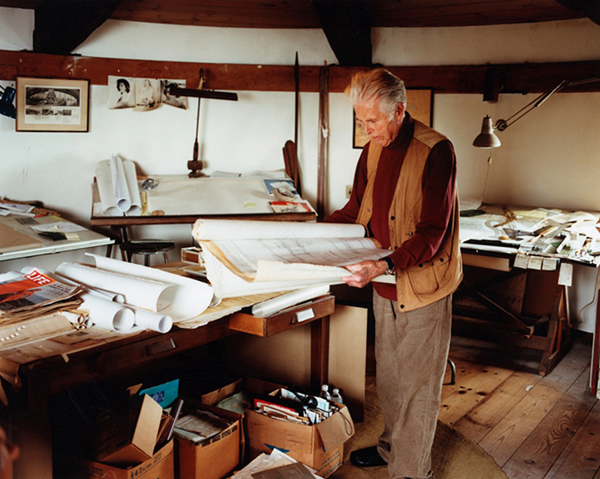

How about your legacy? What will happen to your archive, for example?

My archive is in the very safe hands of Lisa Stoddard, who is doing a great job looking after it and will continue to do so. It’s currently in my garage, and I would love it to go the Getty Center. As for my home, Sandcastle House, it will be 50 years old in four years from now and will therefore be eligible to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

What is the biggest challenge that architects face today?

I think it’s to get away from the grid and design self-sufficient homes—right down to the collection of water. We need to find ways to stop polluting. If we don’t get away from fossil fuels, we will cancel ourselves out with pollution. My biggest interest, all through my life, has been the environment. We are so fortunate to live on this beautiful planet. We must take action to stop ruining it and live in balance with nature. We need to reassess our place in this world—and architecture is a small part of doing that.

Watch the film Harry Gesner: Architect, Environmentalist, Visionary by Eric Minh Swenson »

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

_______

Harry Gesner is the guest of honor at the Iconic Houses conference at the Getty Center, February 17–19.

Text of this post © Jane Szita. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.