Postcard issued by Galerie G. Cramer at 38 Javastraat in The Hague, The Netherlands, circa 1967, showing the interior of the gallery. Architect: J. Rietveld. Foto: Frequin. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5

A rare resource for the study of the art market in Europe during World War II is now available for research at the Getty Research Institute: the correspondence of Gustav Cramer and his son Hans Max Cramer, owners of the G. Cramer Oude Kunst gallery in The Hague, The Netherlands.

Gustav Cramer, originally from Germany, opened a gallery in Berlin in 1933. In 1938, in order to escape anti-Jewish persecution by the Nazi regime, he moved his family to the Netherlands and reopened the gallery at Javastraat 38 in The Hague, where it is still in operation today.

Soon after the invasion of the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, Cramer found himself in the midst of a “rejuvenated” art market. Wealthy German private buyers and art dealers flooded the country, and agents operating on behalf of the Nazi government settled in the Netherlands, which was rich in Dutch and Flemish old master paintings, to make large-scale purchases for senior officials. Gustav Cramer became one of many art dealers engaged as an intermediary in such transactions.

Cramer was involved in business dealings between Nazi agents and private sellers, who often preferred to remain anonymous. The records of these exchanges provide insight both into the range of Nazi collecting strategies, such as forced sales or confiscation of Jewish-owned collections, and into the complex state of the Dutch art market during the war, when firms attempted to conduct business as usual despite Nazi occupation. After the war Cramer provided important information to institutions in charge of the postwar recovery of looted art, such as the Dutch organization Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit. His gallery’s wartime records are complete and uncensored and thus offer a rare resource documenting the international art market in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Among the agents operating on behalf of Nazi government who contacted Cramer was German art historian Erhard Göpel (representing the Reichskommissar für die besetzten niederländischen Gebiete); also Walter Andreas Hofer (representing the Stabsamt des Reichsmarschalls Herman Göring); and Hans Posse, director of the Staatliche Gemäldegalerie Dresden (state paintings gallery in Dresden), who was in charge of building Adolf Hitler’s never-realized art museum in Linz, Austria, known as the Sonderauftrag Linz. Cramer also corresponded with Posse’s middlemen Wilhelm F. Wickel. In 1947, Cramer had an extensive exchange with lawyer C. Reinders Folmer in Amsterdam about Nazi looting of the Paul Hartog collection, and in 1948 he corresponded with art collector Dirk Hannema, who was instrumental in the sale of part of the collection of Franz Koenigs.

The archive is also rich in detail concerning activities of numerous other prominent German and other European art dealers and private collectors. During the war Gustav Cramer corresponded most extensively with Karl Haberstock, Hans Hartig, Hans W. Lange, and Hans Rudolph, all in Berlin.

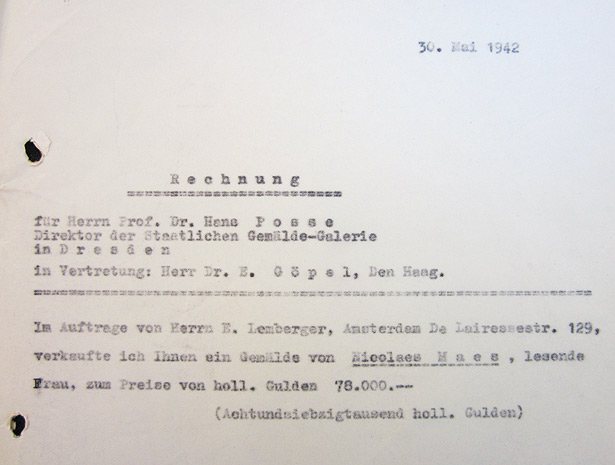

The following examples, letters from Gustav Cramer to art collector Ernst Lemberger in Amsterdam, and to Hans Posse and Erhard Göpel, show the research value of his wartime correspondence. (Click images for a larger view.)

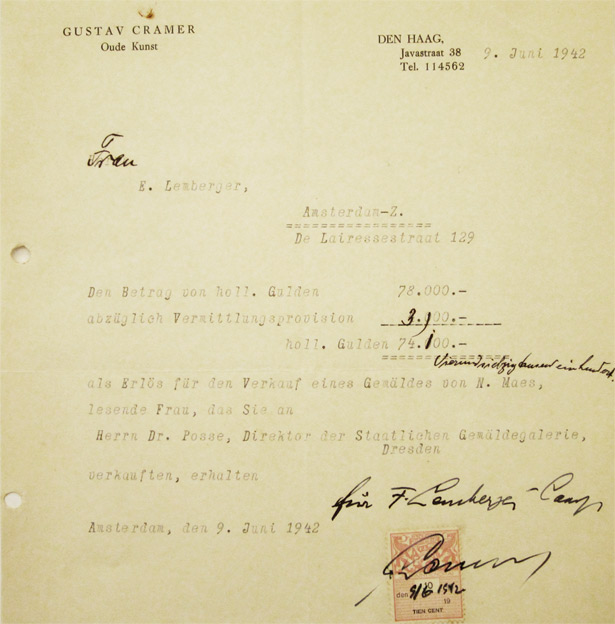

Letter addressed to the wife of Ernst Lemberger dated June 9, 1942. Cramer confirms payment for a painting of a reading woman (“lesende Frau”) by Nicolas Maes, sold by Lemberger to Hans Posse at the Staatliche Gemäldegalerie Dresden. Included is the sale price (78,000 gulden) and Cramer’s commission fee (3,900 gulden). The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5, box 7, folder 10

Letter to Ernst Lemberger dated June 30, 1942. Cramer returns to Lemberger photographs of paintings by Nicolaes Metsu and Jan Steen and states that he has forwarded the two photos and an expert opinion on a painting by Anthony van Dyck to Erhard Göpel, who has shown them to Posse. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5 box 7, folder 10

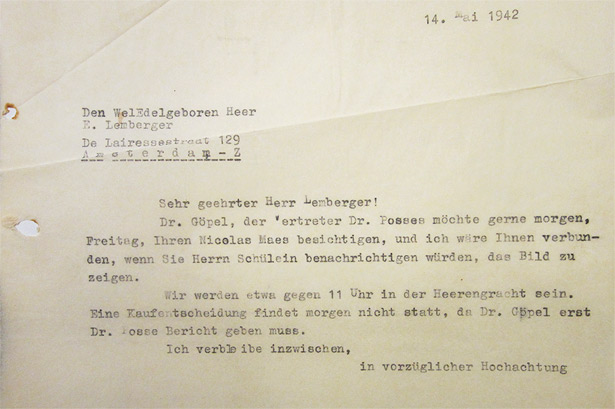

Letter to Ernst Lemberger dated May 14, 1942. Cramer arranges a meeting between Göpel, representing Posse, and J. Schülein (from the bank Gebr. Teixeira de Mattos in Amsterdam) to view a painting by Nicolas Maes. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5 box 7, folder 10

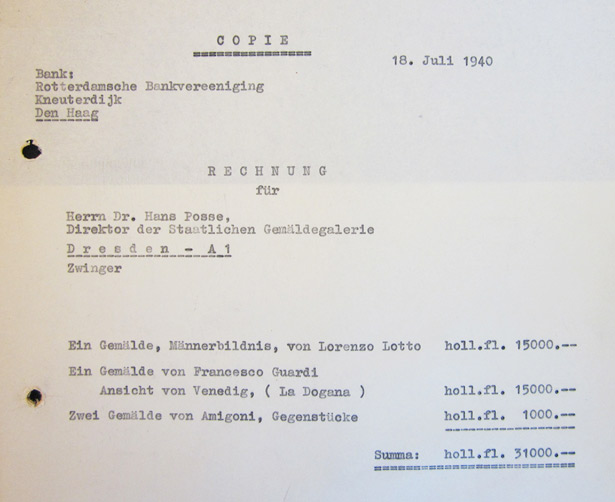

Letter to Hans Posse and invoice dated July 18, 1940. The invoice lists paintings by Lorenzo Lotto (portrait of a man), Francesco Guardi (view of la Dogana in Venice), and Jacopo Amigoni (pair of pendants). The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5, box 5, folder 9

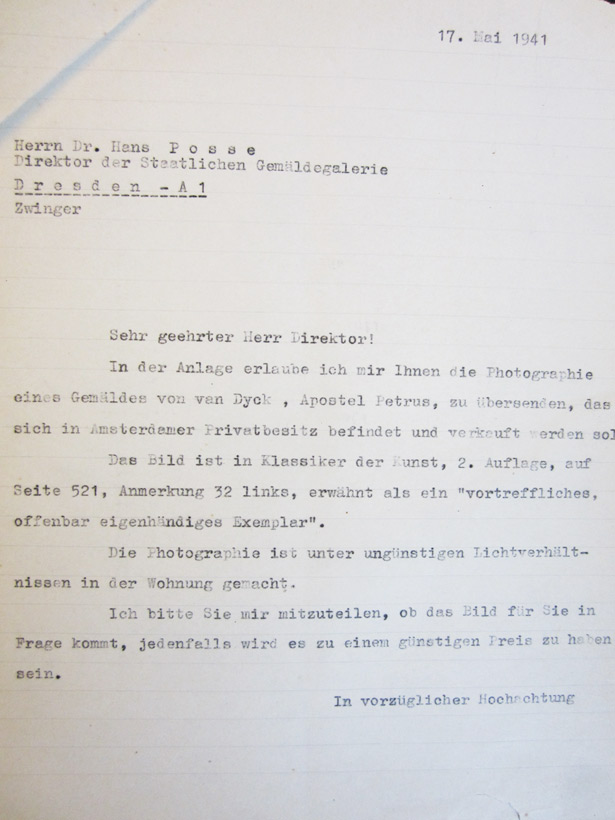

Letter to Hans Posse dated May 17, 1941. Cramer offers for sale a painting of the Apostle Peter by Anthony van Dyck from an undisclosed private collection. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5 box 6, folder 13

Invoice from May 30, 1942, to Erhard Göpel, representing Posse. The invoice confirms the sale of the painting Woman Reading (Lesende Frau) by Nicolaes Maes, sold by Cramer on commission for Ernst Lemberger. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.M.5 box 7, folder 12

After the war, Gustav Cramer’s son Hans Max Cramer increasingly engaged in selling art to museums and private collectors in the United States. The gallery’s correspondence from the postwar period details the process of dispersal of older private European collections at the time when American museums and private collectors were expanding greatly.

The gallery’s correspondence in the GRI archive dates from 1936 to the late 1990s. The correspondence from 1936 through the late 1960s is available for access now; the remainder of the collection, including financial records and photographs, is still in process and will be made available for research upon completion.

See all posts in this series »

Erhard Gopel was purchasing art destined for Hitler or the proposed Hitler Museum. His PhD was on van Dijk. In October 1943 Gopel met with the leaders of the German occupation in Netherlands and got them to defer or alter deportation plans for a number of Jewish art experts, including Cramer, with the rationale that they were of use to him in purchasing art for Hitler – all of which was later considered forced sales. One of the people (families actually) protected, was my uncle, Lion Morpurgo. What the documents you display show is that Cramer was dealing, profiting, from his dealing with the Nazis long before being protected by Gopel. Cramer probably knew Gopel from previous dealings in Dresden, and because of Gopels PhD thesis – Gopel did not reach Amsterdam/The Hague until late 1941, early 1942 with the Hitler Museum assignment.

My grandfather was Paul Hartog. I had not read this article before, and would be most interested in researching the Getty website as more information becomes available. Our family has worked with Chris Marinello and Monica Dugot in the past. There remains more than two dozen paintings of Paul Hartog that are mossing. Regards, Andy Rosson 503-680-9891