An ancient Roman sculpture of a drunken Satyr arrived in the Getty Villa conservation labs on loan from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples in the fall of 2018. This was the first time the 2,000-year-old sculpture had ever left Italy. The bronze depicts a Satyr, a companion to Dionysos, the god of wine.

Satyrs are often shown drunk, and this one is toppling backward, head thrown back. He’s propped up on a rock, resting on a lion skin and a wine bladder. He raises his right arm, snapping his fingers as if calling for more wine. The statue would eventually go on view in the exhibition Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri, but first it would undergo over a year of intensive study and treatment.

We documented the arrival, analysis, and treatment of the ancient statue over the past 15 months. It is one of only a handful of large-scale bronzes to survive from antiquity, and the chance to get up-close and personal through the process was too exciting to pass up.

As part of Getty’s philanthropic work, our conservators frequently collaborate with institutions around the world to study and treat masterpieces from their collections while they are with us on loan, returning the works in better condition than when they arrived.

To prepare a sculpture of this historical significance and scale takes a village and a passionate leader. That leader was antiquities conservator Erik Risser.

Arrival: October 2018

Once packed, the nearly 2,000-pound sculpture (including its stone base) was craned out of a window in Naples, Italy, and loaded onto a truck waiting at street level. It was then loaded onto an air freighter so it could make its way to Los Angeles.

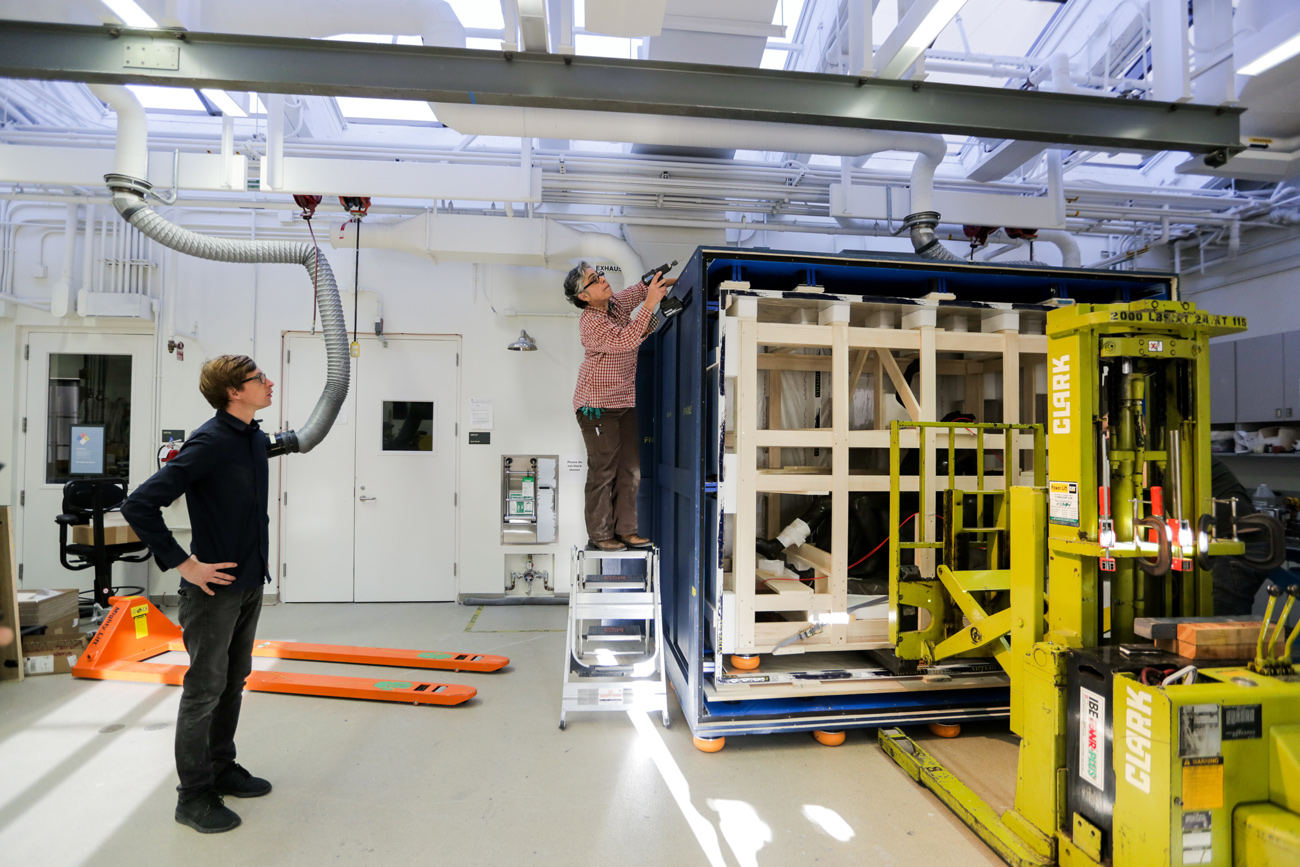

To unpack the sculpture, lead preparator Rita Gomez stands on a ladder, removing screws from the crate as assistant conservator William Shelley watches.

Preparator Andrew Gavenda removes screws from the wooden frame containing the Satyr.

Antiquities conservator Erik Risser (left) and assistant conservator William Shelley (right) assess the arrival condition of the Satyr.

As the exterior blue crate and wooden frame were dismantled screw by screw, Erik Risser and assistant conservator William Shelley documented the arrival condition.

The red wire shown here was connected to a device that measured force and impact, so the team could determine how the journey had affected the sculpture.

The Drunken Satyr is fully freed from the crate and sits on a plank of wood in the conservation studio.

A few hours later, the Satyr was freed from its travel crate and left to acclimatize to the conservation lab. Metals can be reactive to their environments, especially to humidity in the air, so a slow and steady introduction to a new place is best.

Welcome to Los Angeles, Mr. Satyr.

Analysis Begins: November 2018

A team of experts, including curators, preparators, conservators, scientists, and others across the Getty Villa started a thorough analysis of the Satyr. Different techniques and tools were used to gather information about the object. This helped the team make decisions about what needed to be done, and importantly, what needed to be learned before proceeding.

Erik Risser (L) and William Shelley (R) work under ultraviolet light.

The conservators used ultraviolet light to examine the sculpture. Thanks to historical records, they already knew that this ancient bronze sculpture underwent restoration work in the 18th century. By turning the lab lights off and the ultraviolet lights on, they could see the organic material that was used by the 18th-century restorers.

They learned that the 18th-century restorers used a resin, like a glue, to hold the ancient bronze sculpture to the recreated rock beneath it. The little speckles that look like dust in the photo above cannot be seen with the naked eye.

X-ray compilation of the Satyr.

X-rays of the Satyr posted in the Getty Villa conservation lab.

Individual X-rays were taken of the Satyr and a composite image was created so the conservation team could look under the surface.

The X-rays revealed that individually cast parts of the statue were joined together with welds or mechanical techniques (like using a screw to hold a part in place). This step also helped differentiate elements from the original ancient bronze and the 18th-century restoration work.

This information was used by researchers to understand how the sculpture was changed or damaged by the volcanic eruption that buried it in the year 79, and by the excavations that rediscovered it in the 1750s.

The conservators also used a microscope to look at the surface of the bronze magnified 20 to 50 times. During the ultraviolet light examination, they noticed that areas like the left hand, teeth, and face were weak. Using the microscope, they looked for cracks, corrosion, and other surface conditions.

William Shelley examines the sculpture with a microscope.

A look into the microscope at the surface of the bronze. This is the Satyr’s finger.

Erik and William also looked inside the sculpture to get a better sense of the stability of the internal structure, and to see potential weak areas from the inside out.

To see inside, they used an endoscope, a long, narrow tube with tiny cameras on the end. These are normally used for medical procedures on humans but are often repurposed to look inside artworks like this one.

The endoscope revealed wood, ancient pins, newspaper, and even a rolled-up Neapolitan funicular ticket inside of the Satyr.

A view of the endoscope camera feed.

William Shelley inserts and guides the endoscope with his left hand, and monitors the camera feed with his right.

Analysis and Science: February 2019

Getty Conservation Institute scientist Monica Ganio (left) and William Shelley in the lab.

Scientists from the Getty Conservation Institute often collaborate with art conservators to bring their scientific expertise to bear. In February, scientist Monica Ganio used an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer to understand the elemental compositions of materials. XRF is a useful tool for the analysis of metals, including bronze, because different elements typically found in bronze–notably copper, tin, and lead–produce a unique, or characteristic, signal upon excitation by energetic X-rays. This analysis was done without removing any samples from the sculpture.

After three days of performing XRF on over 200 different points across the entire sculpture, Monica calculated the composition of the metal across the sculpture. This step enabled the conservation team to make better-informed decisions about the treatment.

All the points on the Satyr where XRF was performed.

Monica Ganio takes a reading with the portable XRF device.

Disassembly: February 2019

Armed with a solid understanding of the inner and outer structure of the Drunken Satyr, the conservators were ready to remove the ancient statue from the 18th-century stone base in order to address internal damage, clean the overall sculpture, and study the interior.

Erik Risser and William Shelley remove the lion skin drapery.

First, they turned their attention to removing the individual pieces of the bronze lion skin that draped under the figure. They removed the adhesive that was applied in the 18th century to hold the Satyr figure to the lion skin and rock. The adhesive was already failing in places, so the team decided to remove it altogether.

Next, they carefully removed 18th-century bolts and screws that were holding the lion skin pieces onto the rock. They removed the lion skin piece by piece until all that was left was the figure on top of the wineskin.

There was an old newspaper rolled up and stuffed between the figure and the base, potentially done as a way to stabilize the figure.

Rolled-up newspaper revealed.

With the lion skin drapery removed, the anchors are also revealed.

Anchors that were fabricated in the 18th century revealed themselves in the marble base. You can also see the areas of unfinished rock that the stone carvers must have known would not be visible in the final product.

With the pieces of the lion skin removed, the team could compare those originally cast in antiquity with the pieces that were made to match in the 18th century. The undersides also revealed debris from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius on the ancient piece, and drips from the patina on the 18th-century reconstruction.

On the left, the original ancient lion’s face; on the right, a piece of the lion skin that was made after excavation.

The underside of the removed lion skin. On the left is the ancient piece, on the right is the 18th-century piece.

Making a Machine to Move the Satyr: February 2019

The sculpture is nearly 2,000 pounds of bronze and stone—but for work in the conservation studio to continue, it needed to be mobile. So the team designed and built two lifting systems. The first was able to lift the entire sculpture, including the base. The second was a lift to carefully separate the bronze figure from the stone base, a feat that seems not to have been attempted since the sculpture was excavated and repaired in the 1700s.

A metal plate was cut to fit perfectly beneath the marble base that the Satyr sits on.

A thick metal plate is custom cut to fit beneath the rock base.

The lift designed for the entire 2,000-pound sculpture was made with a combination of foam, resin, and metal to create pieces that could be pressed against the base to compress and lift. Metal scissors were also custom fit with resin at the ends that perfectly grip the form of the Satyr torso in four places. The scissors were then carefully connected to a gantry lift, which facilitates a controlled lift. The scissor design evenly distributed pressure and weight so that the sculpture could be separated from the rock slowly and carefully.

Nicely done, team.

Testing the compression lift.

Lifting the Figure: February 2019

For the first time in more than 250 years, the Satyr was separated from its 18th-century stone base so that the interior could be studied. The team hoped to better understand how it was originally made and how it was restored in the 18th century, and to assess the condition of the bronze from the inside out.

Erik Risser, William Shelley, and Marcus Adams guide the Satyr to a nearby rest.

After the custom scissors were secured, the gantry lift was rolled into place. Bit by bit, the sculpture was lifted, and when it was high enough to clear the base, it was gently rolled to a nearby surface. The process took months of careful planning, but less than an hour to execute.

Erik Risser gently guides the Satyr mid-air.

Curator Kenneth Lapatin inspects the base with the sculpture removed.

The opportunity to see the inside of ancient bronzes is rare, so this was a special experience for everyone. Some surprising observations included a piece of wood that may have been used as a stability mechanism, a rip along the Satyr’s back that was more intense than expected, and the discovery that the right arm was filled with bronze. Finally, inside the sculpture they found a funicular ticket from Naples along with old newspapers.

A close look at the underside of the figure revealed rough ripped edges showing the damage to the sculpture during the eruption of Vesuvius, when the figure was ripped off its original base. That base has never been recovered.

Also revealed was a cutting in the bottom of the Satyr’s left foot, which showed how it was attached to its base in antiquity.

Naples funicular ticket.

The underside of the Satyr.

The underside of the Satyr’s left foot.

Conservation of Rock: April 2019

The stone base was fabricated in the 18th century shortly after the ancient statue was excavated, and while the restorers did their best to sculpt a composition that would match the ancient sculpture, it had weakened and cracked over time.

The stone was also waxed repeatedly, which had gradually discolored the rock. It was due for a good cleaning, so Erik got to work.

As Erik studied the base up close, he glimpsed the past, into the minds of those who had previously restored the Satyr. In the markings left in the stone, he pieced together the coordinated effort of the stone carvers. The visible tool marks show the initial carving and later adjustments to allow for a better fit for the bronze figure.

With the figure separated from the stone base, Erik Risser was able to work underneath it.

On the interior, he analyzed the extent of the structural cracks. Some that had existed for a long time, and some had been plastered over to keep them from getting worse. Erik gradually removed the plaster to better assess the cracks from the inside out.

He filled all the cracks with a reversible resin using a syringe and cleaned the exterior of the rock. He also applied solvent cleaning gels in tiny squares, which allowed him to control the concentration and the length of time the solvent was in contact with the surface.

Paper Conservation: April 2019

In the Getty paper conservation studio, conservator Nancy Turner began examining all the rolled-up pieces of newspaper recovered from the sculpture. The conservators hoped that by unrolling the newspaper, they could get lucky with a printed date, name, or event to help assign a time period to this particular stage of work.

Paper conservator Nancy Turner works to unroll the newspaper.

Ultrasonic mister at work.

This device is called the ultrasonic mister. Nancy normally uses it to turn liquid adhesive into a mist, but in this instance she used water. By carefully adding moisture to the newspaper, she was able to slowly unfold and unroll the paper.

The paper revealed a print date of September 19, 1970. That helped the conservators estimate when the paper was inserted into the statue, and provided a rough date for a previously unrecorded conservation intervention. The Villa dei Papiri galleries at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples were reinstalled in 1971, so it makes sense that a relatively recent newspaper would have been used in anticipation of that project.

Newspaper successfully unrolled.

Reassembly: May 2019

The Satyr figure, the lion skin, and the stone base sit in separate parts of the conservation lab.

Conservation work on the Satyr figure, the lion skin, and the rock were completed, and it was time to reassemble the sculpture. Putting the Satyr back together was a delicately choreographed routine that involved a custom mechanical attachment system.

The dark shape on top of the stone base is a cast interface. This will support the sculpture internally.

From another angle, Erik Risser demonstrates how the interfaces are attached to the lion skin.

What you see in these photos are “interfaces.” They are resin casts, made to fit exactly in place on the surface of the rock underneath the bronze. Fourteen separate and sometimes interlocking interfaces were cast.

They form a complicated puzzle that keeps the Satyr secure (no glue required). To remove the Satyr from his rock, you’d have to perfectly reverse the sequence of construction.

The interfaces make it so that there is only one correct position in which the Satyr figure will rest. Since there is only one way to attach him, we know he is secure and stable.

The interface sits between the two bronze components of the sculpture.

Preparing for Installation in the Galleries: June 2019

After the Satyr was fully reassembled, Erik started on the aesthetic integrations—including creating fills, and painting the interface edges the same color as the object.

Marcus Adams and Erik Risser lift the Satyr and prepare for its move into the galleries.

When installation day arrived, Erik and Marcus loaded the completed sculpture onto a dolly so it could be rolled into the galleries.

Erik Risser wheels the Satyr on a dolly.

Erik Risser, Marcus Adams, and preparator Cesar Santander roll the Satyr out of the conservation lab.

After months of work, the Satyr finally left the conservation studio and went on view as one of the centerpieces of the exhibition Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri. He helped tell the story about otium, or the life of cultured leisure that ancient Romans enjoyed in their luxury villas.

The Satyr on view in the Getty Villa’s galleries. Drunken Satyr, 1st century BC – 1st century AD, Roman. Bronze, H: 137 cm. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, inv. 5628. Reproduced by agreement with the Ministry of Cultural Assets and Activities and Tourism. National Archaeological Museum of Naples – Restoration Office

Packing and Shipping: November 2019

While the Satyr was on view in the galleries, Erik prepared a new adjustable cage to carry the sculpture safely back to Naples, Italy, after the exhibition.

When Buried by Vesuvius closed, the Satyr was packed up in the custom crate.

Senior preparator Dan Manns works alongside Erik Risser to build the inner crate.

Dan Manns inserts screws into the metal cage.

The Satyr also returned with a new custom lifting mechanism to make the job of the team back in Naples easier when they move the sculpture.

A closeup of the custom lifting mechanism. A piece of resin is cast to perfectly conform to the rock, and the cut metal plate is shown beneath.

Part of Erik’s job is documentation; after all, his work over the past year on the sculpture is another chapter in its history. This documentation provides an invaluable source of information about all the recent analysis, study, insight, custom designs, and treatment.

The most exciting part? “We gained a much clearer understanding of both the Satyr’s ancient production and how it was restored in the 18th century, as well as the working methods of both ancient and early modern craftsmen,” says curator Kenneth Lapatin.

A piece of Italy’s ancient cultural heritage not only went back to its home museum stabilized for centuries to come, but also better studied and understood.

So confused why you sent this out when it’s gone? How is it a current article?

Hello, Thanks for taking the time to comment. We waited to finish documenting the object’s complete journey, which included not just its conservation and exhibition but also its careful packing and return to Italy after the exhibition.

Thank you for letting me read this article now I’ve learned even more interesting things and facts and the history behind all this. THANKS!!!!

Thank you for this. It was a lovely read.

Il restauro deve essere stata una avventura irripetibile ed esaltante.

What feature or characteristic makes him a satyr, not just a man? Wonderful article. Thanks for it and especially the pictures.

Thank you for a most informative piece. I would be interested in reading a more comprehensive report of the restoration work, most particularly on your treatment and restoration of the bronze statue itself, as well as its conservation philosophy regarding later additions to the work? If so, please indicate how it may be accessible to the public. I believe that your work is extremely valuable and I applaud the efforts of your scientific and conservation staff. .

So interested in this!!!

Much more visual material is required to really get an idea. Shame that this is mostly text with a few rather vague photographs and I have to agree – I would have loved to see the exhibition after this article.

Missed opportunity but thank you for doing what you did!

Impressive!

What a great article!

I was wondering what was done to the bronze itself in terms oc conservation treatment?

Thank you in advance for you reply.

Laurence Gagné

Principal Conservator

DL Heritage inc.

Montréal, QC, Canada