Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

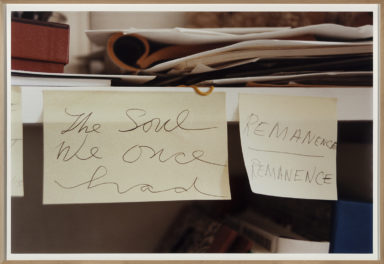

“Everything was made of the most familiar objects. It could’ve been taken off a desk or a kitchen counter or something, and put into action. They were inert, but their meaning wasn’t. I thought to myself, this isn’t art; it’s better.”

In the early 1960s, artists from around the world practicing in wide-ranging disciplines—from music to dance, visual art to poetry—began to coalesce in a movement called Fluxus. Fluxus grew out of the absurdity of Dada, Surrealism, and Futurism, drawing inspiration from influential artists like Marcel Duchamp and John Cage. Although the movement ended in 1978 with the death of its founder, George Maciunas, its approach to artmaking continues to inspire artists today.

In this episode, art critic and Fluxus expert Peter Frank discusses the movement’s history and impact, sharing his personal engagement with Fluxus that began during his childhood in New York City. This conversation took place on the occasion of the Getty Research Institute’s exhibition Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive, which is currently on view at the Getty Center through January 2, 2022.

Your Name Spelled with Objects, for Jeannette Brown, 1972, George Maciunas. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (890164). © 2021 Estate of George Maciunas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

More to explore:

Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive explore the exhibition

Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive buy the book

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

PETER FRANK: Everything was made of the most familiar objects. It could’ve been taken off a desk or a kitchen counter or something, and put into action. They were inert, but their meaning wasn’t. I thought to myself, this isn’t art; it’s better.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Peter Frank about the avant-garde art movement known as Fluxus.

Fluxus was an avant-garde international and interdisciplinary art movement of the 1960s and 1970s engaging artists as diverse as John Cage, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono. Over the years, the Getty Research Institute has collected works by these and other Fluxus artists, including Alison Knowles, Dick Higgins, George Maciunas, Ben Patterson, and Robert Watts.

On the occasion of the Getty’s exhibition Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive, I spoke with Peter Frank about the meaning and character of Fluxus. Peter is associate editor for Fabrik Magazine and former senior curator at the Riverside Art Museum, as well as art critic at The Village Voice and The Soho Weekly News.

Okay, thank you, Peter, for joining me on this podcast.

FRANK: Thank you.

CUNO: And let’s begin with the term Fluxus. Give us a definition of it.

FRANK: Well, your upcoming exhibition says it all with the title, “Fluxus means change.” The term, derived from the Latin, indicates that nothing is permanent and invincible to metamorphosis, and that in fact, change is the nature of life, and particularly of art.

CUNO: Who were its founders? And is it even right to say there were founders?

FRANK: Yes. As a movement, Fluxus, you could say, was founded by George Maciunas. As a sensibility, it existed before and survived the condition of Fluxus as a movement. Because what Maciunas sought to do, at least initially, with his Fluxus organizing, even before it was Fluxus, when he had the gallery in New York on Madison Avenue, he wanted to present what he and his friends and colleagues considered the cutting edge in various of the arts.

And so I think George conceived of Fluxus not as a moment per se, with it own distinct practices, but as a clearing house for a range of related, but often distantly related, movements and practices, like Nouveau Réalisme in France and Italy or the nascent Pop art of the Independent Group in Britain, or happenings in Germany and the United States, and like that. It was called the New Sensibility, at the time.

Fluxus emerged from a sensibility that itself was emerging in the latter half of the 1950s. And the stage was set for Fluxus itself to emerge in the very early sixties. It consolidated in 1962, and endured until Maciunas’ own death in 1978, as a movement.

But its most active period could be said to be 1962 to ’66. After that, Maciunas got involved— preoccupied with another project, that is, creating SoHo. He was one of the first to coopt the loft buildings in SoHo for artists’ use.

CUNO: To what extent was Fluxus international and interdisciplinary?

FRANK: Entirely. It always thought of itself, or the artists involved in Fluxus thought of themselves as operating on an international scale, and came from all forms of artwork—poetry, music, dance, visual art, theater. In fact, I think it’s historically accurate to note that if Fluxus began as any one type of movement, [it] began as a movement in music.

CUNO: What was its relationship to Dada and Surrealism?

FRANK: Fluxus was self-consciously a direct descendant of Dada. In fact, the first concerts of Fluxus were called Neo-Dada in music. Those are the ones staged in Wiesbaden and other German sites in 1962. Relationship to Surrealism, on the other hand, was quite a bit more distant, and mostly through Dada.

I think the relationship, not political but practical and aesthetic, to Futurism was stronger than to Surrealism, although the few Futurists practices that anticipated Fluxus, those weren’t so well known at the time to the artists and people around Fluxus as they became subsequently. These phenomena, historical phenomena were known of at that time in the early sixties to American and Western European avant-garde audiences. But they weren’t known per se.

CUNO: Was that all one generation you’re describing, or were there multiple generations involved?

FRANK: It was one generation, I would say, but with distinct roots in the practices of previous generations and the practices of previous avant-garde artists.

CUNO: Would you consider Duchamp—

FRANK: Duchamp is the example of that.

CUNO: Yeah.

FRANK: He was the grandfather of Fluxus and its entire new sensibility.

CUNO: And where in the world are you talking about? Was it in New York? Was it in Paris? Was it in London? Was it in Los Angeles?

FRANK: To various extents, all of these places. Los Angeles, not so much at the time, although soon thereafter. The Bay Area, to a greater extent.

But New York was the center, as far as American Fluxus and American post-neo Duchamp activity happening. In Europe, it was wherever the art centers were—Paris, Milan, Berlin, Cologne, London to a somewhat lesser extent.

CUNO: What about John Cage?

FRANK: John Cage was, perhaps to his chagrin, a direct progenitor of Fluxus. In fact, one of the source moments for Fluxus was the seminar he conducted at The New School in New York between 1956 and ’58, in new music and new music performance. A number of the artists of all types who went on to found Fluxus attended those seminars.

And when Maciunas signed up, Cage had left for a tour of Europe and put the electronic composer Richard Maxfield in his place. But Maxfield turned out to be of a like mind and a like perspective, and had a profound influence on Maciunas. This was the late fifties. Or around 1960.

It was as a result of going to that class with Maxfield that Maciunas attended the concerts and performances that were hosted by Yoko Ono and La Monte Young down on Chambers Street, which inspired Maciunas to open up a gallery uptown.

CUNO: What about Dick Higgins?

FRANK: Dick was, certainly in English, the foremost theorist for Fluxus, intermedia, and related topics. And as a result, I consider him one of the most important artists in Fluxus and in fact, in artistic activity of the postwar era.

CUNO: When did you first come across Fluxus?

FRANK: On December 27th, 1963.

CUNO: And what happened on that day?

FRANK: I was thirteen at the time, going around to galleries with my grandmother. I’d recently developed a passion for art and started going to galleries. This was, like, my second or third tour.

This is in New York, of course, where I grew up. Walked into a gallery called Thibaut. The art critic Nicolas Calas had put together a show called The Hard Center, playing on the idea of the hard edge, which was the new anti-Abstract Expressionist abstract painting. Ellsworth Kelly and such. But no, it was the hard center, like a candy.

I walk in and the first thing I see is a cane chair with a green rubber ball sitting on it, and a white walking stick, which I realized later had a little rainbow painted on its business end.

I knew about Duchamps readymades already, so I could understand like that, in that format, in that context, but it seemed to have more dynamism. The Duchamp readymades seemed fixed; they were what they were. This chair, which turned out to be by George Brecht, seemed to be a performance. I could feel it immediately. It wasn’t just a thing; it was things in flux. I use that term retrospectively, but that’s how I felt at the time.

Same with the other items in the show. There was a box that Walter De Maria had crafted out of wood, into which a two-by-four could be slid. There was a chessboard. Both sets were the same color—I can’t remember if white or black—which was Calas’ reconstruction of Yoko Ono’s chessboard.

There was a stamp dispenser that dispensed stamps, the likes of which I’d never seen, which had been printed by Bob Watts. There were three lead yardsticks, one of which was shorter than the other two, that were crafted by Robert Morris. Et cetera, et cetera. And I looked around, and everything was made of the most familiar objects. It could’ve been taken off a desk or a kitchen counter or something, and put into action. They were

CUNO: So what happened in your life between then and your mature years of your late twenties?

FRANK: I continued to go to galleries. I also made contact with some of the Fluxus artists. Most of the ones in New York. Al Hansen, who was— had one foot in Fluxus and one foot everywhere else, I met a few months after that encounter with The Hard Center show. And he’d seen me running around the galleries before, so he slipped me a sheet of Bob Watts stamps, and I was his acolyte forever.

I knew he did happenings, but I never saw one. But then he published a book about happenings a couple years later. He said, “Come with me down to the publisher’s and I’ll sell you a copy of my book for cost, wholesale.” Well, a book on happenings at a bargain price—who could resist?

CUNO: Did you ever identity yourself as a Fluxus artist or an advocate?

FRANK: Yes. Artist, secondarily, at best. I mean, I’d done some written pieces and performance pieces as Fluxus. I think I didn’t dare consider myself a Fluxus artist or a Fluxus writer or— until I was fully on the New York scene, after finishing undergraduate school at Columbia. But an advocate, well, from the get-go. Certainly, from once I knew what Fluxus was all about, which I did as of meeting Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles, through Al Hansen, whose book had been published by Dick’s Something Else Press.

All took me down to meet Dick in April of 1966. Dick sold me his book, at full price, and I think Alison’s Great Bear Pamphlet. And the idea that these books were not books about art, but were art themselves opened up a world, another world of possibilities for me. First, I could see objects performing; now I could see books as artworks. And everything became energized with regard to everything else, I think the best way to put it. Certainly for somebody in his adolescent years looking for, I guess, revelation. Small revelations, so I could fit them into my daily life, but revelations nonetheless.

CUNO: What were you doing at the time?

FRANK: I was in high school. I started college in 1968. But in high school, I actually staged a happening with a friend of mine. I staged a couple happenings, several happenings at summer camp. One year, it turns out that a fellow camper was a good friend of Allan Kaprow’s, so that made staging a happening at the camp imperative.

CUNO: You wrote art criticism in New York for The Village Voice and the SoHo Weekly News in the seventies. Was Fluxus on your beat?

FRANK: Very much so, as much as I could make it so. Fluxus was, to some extent, in eclipse in the seventies and into the eighties. People were aware of it, but it was last decade’s hot stuff. I, on the other hand, remained a true believer. Not at the expense of my appreciation of other phenomena, older and newer, more and less conservative, but as well.

The Conceptual artists, who were coming out of Minimalism at the time, either rejected Fluxus or pretended they didn’t know it existed. I knew better than that. But the important thing was that Fluxus itself had prepared me for what they were proposing. And that in the work of someone like Lawrence Weiner or Robert Barry, I could see not simply visual art become verbal, but I could see visual art become poetry. I think the poetic aspects of someone like Weiner are, to this day, under stressed, not well understood.

CUNO: Yeah. What brought you to Los Angeles? I think you came in 1988.

FRANK: At the end of ’87. As a native New Yorker, I felt that I— The New York art world, and New York in general, had come to be preoccupied with fame and money. And the discourse of art itself hadn’t disappeared, but it kind of had gotten underground and it wasn’t dictating what people thought about.

I’d been coming to LA, and San Francisco for that matter, at least once a year since 1975 for professional reasons, and became increasingly taken with the fact that certainly in Southern California, the discourse was that of artists first. That there were so many artists here working in so many different ways, so many of them ways I hadn’t really seen before.

And they suffered from lack of commercial success, but not lack of exposure. There was, you know, a sprawling network of college campus galleries, where they would show, or alternate spaces. And also employ— would employ them as teachers.

CUNO: You mentioned the idea that colleges and universities provided good spaces for performance. I’m thinking of Mills College, as far north as the Oakland area, but also Pomona College.

FRANK: Not just performance, but also exhibiting static work. But Mills is, early on, Mills had an historic position in that kind of thing because it was around much earlier. And in fact, it was a great place to go for music because it employed a number of refugees from Europe.

CUNO: Darius Milhaud.

FRANK: Darius Milhaud, first and foremost. And Steve Reich studied with Darius Milhaud.

CUNO: Yeah.

FRANK: That’s perfect.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, the Getty Research Institute, or the GRI, as you know we call it, has the papers of Dick Higgins. Tell us about Dick Higgins and what his role was like in the develop of Fluxus.

FRANK: As I said, Dick was a central figure in Fluxus. And its foremost theorist, certainly in English, because he brought forth the intermedia theory, and you could even say Fluxus theory. Dick was the one who could most successfully, simply, and inventively theorize the practices and the mindset associated with Fluxus.

And I mean, a number of the participants in Fluxus, Maciunas not least, were resistant to this kind of theorizing, because they felt it pinned down Fluxus. But it didn’t. In fact, it kind of did just the opposite. It dissolved the gesture and the object into the potential.

CUNO: Among other things, Emmet Williams, I think, was the editor of Dick Higgins’ Something Else Press, for which you wrote the definitive bibliography. Tell us more about Emmett Williams and about the press, how important it was.

FRANK: Well, Emmett was one of the leading Concrete poets, particularly in English, and was well connected to the Concrete and visual poetry practice around the world.

CUNO: Maybe our listeners don’t know what that means. Tell us about Concrete poetry.

FRANK: Concrete poetry is an intermedium between poetry and visual art. Visual poetry is probably the best way of describing the context in which Concrete poetry appears, but Concrete poetry is visual only in its typography. Whereas all visual poetry generally incorporates non-typographical elements in the work.

CUNO: Well, tell us about this Something Else Press then, for which Emmett Williams worked, and it was Dick Higgins’ press.

FRANK: When Dick and his wife Alice Knowles return from their European trip, they were— they had been given a list of names to contact, by the composer Earle Brown, who was in Cage’s circle at the time.

And they made contact with Maciunas in Wiesbaden, where Maciunas was working on the U.S. Army base. And I think this was after the first Neo-Dada concert, but before any of the others. So they made contact with Maciunas in Europe. They came back to New York from Europe. Then Maciunas returned to New York and set up kind of a Fluxus outpost on Canal Street.

But Maciunas would come up with ideas for— great ideas for projects and never finish them. Would start them and never finish them. Including publications, book publications, specifically a book that Dick had written. Actually, a back-to-back double book. One book was called Jefferson’s Birthday, the other one, Postface. And Postface was a theoretical exegesis, whereas Jefferson’s Birthday was a compendium of written performance pieces.

Maciunas said he’d publish it; never got around to it. So Dick took the manuscript back from him and published it himself. And that was beginning of Something Else Press. Once Dick found out that he could do it, he wanted to do it for his friends in and beside Fluxus.

And also, he had some experience as a typesetter and a book designer. So he wanted to create books as art objects, or books of the quality of art objects, collectible books, books that were integrally conceived.

CUNO: Now, I mentioned the GRI a couple of times. And I should say that it has the collection of the patrons and collectors Jean and Leonard Brown, which will be the subject of an exhibition and book. The book, you’ve already mentioned, and its title, Fluxus Means Change.

And it will include correspondence with Duchamp, but also Fluxus works by George Maciunas and Nam June Paik, and still more boxes of gathered materials of George Brecht, you’ve already mentioned. This would be a good time to take stock of Fluxus. What do you think Fluxus’ reputation is now?

FRANK: Fluxus has taken on the kind of twinkle of history for younger artists and scholars, the same way Dada did in the sixties, when Fluxus was emerging. And it’s charming and very encouraging to see these attempts at not necessarily understanding Fluxus, but taking inspiration from it, understanding it in a motivational way. Fluxus doesn’t want to be understood as a cadaver to be dissected. It wants to be understand as a, I think, a costume to be worn.

CUNO: What do you think will be next for Fluxus?

FRANK: Further scholarly investigation and certainly, an investigation of its early engagement of women, artists of color, and artists from around the world, not just America and Western Europe. And I should say of LGBTQ artists.

And that in fact, these identity issues with which we’re so concerned now were motivational to Fluxus artists. Not so much when they came together in the sixties, but by the seventies, you find that Fluxus artists and their compeers were active in the feminist movement in New York, in Japan. Were engaged in community support and activity. Benjamin Patterson took a decade out from mark making to work as a social worker in Harlem.

And that there was an unspoken sense of, this kind of thinking is available to and applies to everybody. And the sense of outsider status that so many of the artists in and around Fluxus felt made identifying as something else in the wider world that much easier and more logical.

CUNO: What’s next for you, Peter Frank?

FRANK: Keep my eye out for newer and advanced interpretations of Fluxus, to see Fluxus occupy its historical place without settling into it, and to continue my own work writing about and exhibiting artwork of all types, hoping that some of that work will flash a bit of the Fluxus DNA.

CUNO: Thanks again, Peter, for speaking with me and for sharing your understanding of Fluxus. I look forward to seeing you at the opening of the exhibition Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-garde Archive. Thank you.

FRANK: Thank you.

CUNO: Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive is on view at the Getty Research Institute through January 2, 2022

This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Mike Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts/ or if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

PETER FRANK: Everything was made of the most familiar objects. It could’ve been taken off a desk or...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.