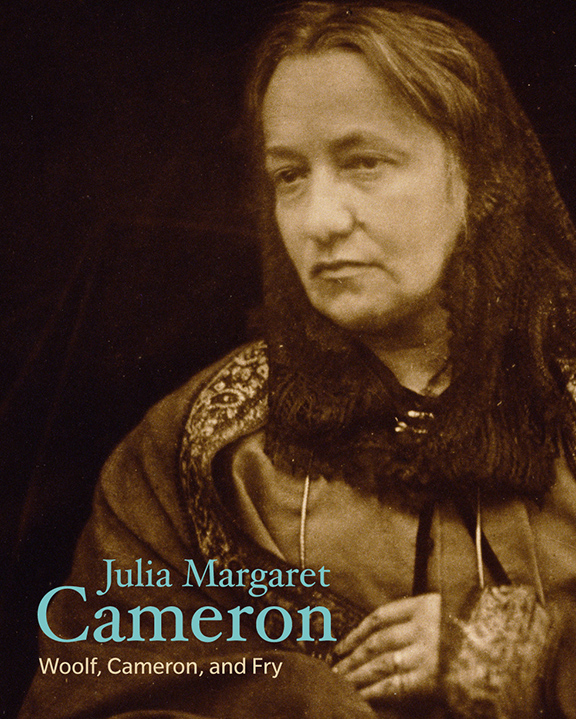

Although 19th century photographer Julia Margaret Cameron did not pick up her first camera until the age of 49, the artistically composed and printed images she made during her short career were both groundbreaking for their time and an inspiration to artists long after her death. In this episode, Getty photographs curator Karen Hellman discusses three biographies of Cameron: one by her grandniece Virginia Woolf, one by art critic Roger Fry, and one by Cameron herself. These biographies were recently published together by Getty Publications in the book Julia Margaret Cameron, part of the Lives of the Artists series.

More to Explore

Julia Margaret Cameron publication

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art & Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KAREN HELLMAN: I think people kind of gravitate towards her photographs naturally. There’s the kind of presence to them that speaks to people today.

CUNO: In this episode I speak with assistant curator of photographs Karen Hellman about the life and work of the 19th century photographer Julia Margaret Cameron.

In its series, Lives of the Artists, Getty Publications has recently published Julia Margaret Cameron, with texts by Virginia Woolf, Cameron’s grandniece, art critic and art historian Roger Fry, and Cameron herself. The texts are in turn witty, sarcastic, poetic, and discursive, leaving the reader with a greater understanding of Cameron’s unconventional life, experiments with early photographic processes, and creative sensibilities. Cameron seems to have known every major artistic and scientific figure in Victorian England. And many of them posed for her. And the resulting work is some of the most beautiful and evocative photographs in the history of the medium.

Julia Margaret Cameron was born in Calcutta, India, in 1815. She was married there twenty-three years later. Her husband, twenty years her senior, was a jurist and a member of the Law Commission stationed in Calcutta. Together they had six children. In 1848, Cameron’s husband retired and the family moved to Tunbridge Wells, in England; and two years after that, to London.

Fourteen years later, Cameron made her first photograph. She was forty-nine years old. A year later, she became a member of the Photographic Society London. Then in 1875, with her family, she moved to Ceylon, today Sri Lanka, where she continued to make photographs. She died four years later, at the age of sixty-four. She is buried next to her husband, in Sri Lanka.

I’m sitting with Getty Museum photography curator Karen Hellman to discuss the life and career of Julia Margaret Cameron. Karen, thanks so much for joining me on this podcast.

KAREN HELLMAN: It’s a pleasure to be here.

CUNO: Now Virginia Woolf begins her account of Cameron’s life like this. She says, “Julia Margaret Cameron, the third daughter of James Prattle, of the Bengal Civil Service, was born on June 11th, 1815. Her father was a gentleman of marked but doubtful reputation, who after living a riotous life and earning the title of the biggest liar in Indian, finally drank himself to death and was consigned to a cask of rum, to await shipment to England.” That’s quite a start for a biography. Now Karen, give us a general sense of Cameron’s life up until she picked up a camera. And give us a sense also, too, if you can, of the state of photography in England at the time.

HELLMAN: It is quite a start for a biography, and fitting for Julia Margaret Cameron, because as Wolf goes on to describe, Cameron inherited her father’s indominable vitality, which she certainly carries into her photographs. She did have a very interesting life. Her father worked for the East India Trading Company and her mother was from French royalty, so she grew up among the European elite in India.

She was educated in France. And in her early twenties, while convalescing in South Africa, she meets two very important men in her life. One was her future husband, Charles Hay Cameron; and the other was John Herschel, who would be one of her connections to photography. After she marries Charles Cameron in Calcutta, they live in India for another decade, and circulate amongst the major social and diplomatic circles there.

And then when they move to England in 1848 with their six children, they join three of Cameron’s sisters in London. And at this time, in 1848, photography had been around for about a decade, so it was still a very new, very young medium, largely dominated by the daguerreotype process from France. And so many members of the upper classes would go to get their portraits taken in these lavish daguerreotype portrait studios that were actually set up to look like Victorian sitting rooms.

CUNO: Was it a curiosity, or—

HELLMAN: It was like a privileged thing to do. Sort of like getting your portrait painting, but cheaper.

CUNO: Did people exhibit them in their homes…

HELLMAN: Yeah. And they’d keep them—

CUNO: …the way we do now?

HELLMAN: Right, exactly. Sort of keep them, hand them down to their children…

CUNO: What was the nature of the process, the photographic process at the time? You said daguerreotype and—

HELLMAN: So in the 1840s, it was dominated by the— The daguerreotype was a silver-coated copper plate that was a one-of-a-kind image, made in a large camera. But by the time Cameron picks up a camera in the 1860s, the processes were quite different.

CUNO: How did she pick up the camera?

HELLMAN: So in 1863, at the end of that year, she was given a camera by her daughter and son-in-law as a present. And by that time, Cameron and her husband had moved to the Isle of Wight, which is an island off the southern coast of England. So they had moved away from London, from the city.

And her daughter, I believe, was afraid she would kind of be too lonely or sort of not have enough to do. She was a very, you know, dynamic woman and very active socially, both in India and in London. So when she moved to the Isle of Wight, they thought, oh, well, let’s give her a camera and she can have something to occupy her time with.

CUNO: Give us a sense of the size of a camera and the kind of apparatus you need to print and to get, I guess, a daguerreotype at that time, to produce a daguerreotype or—

HELLMAN: So at this time, by the time she has a camera, it’s actually glass-plate negatives that she’s making, and contact printing them with albumen paper. So it’s a slightly quicker process than the daguerreotype, but very cumbersome. So she has a camera that’s a large wooden box with a lens on one end. And the size of the plates that she’s handing at first are about twelve by ten inches, which is quite sizeable. And then she actually gets a new camera a couple years later that takes plates fifteen by twelve inches.

So they’re these glass plates that she’s handling in the dark. She’s sensitizing them first. Well, first she has to coat them with collodion, which is a sticky, syrupy kind of substance, and you have to make sure that it goes over the plate very smoothly and without any marks or dust. And then you sensitize that in the darkroom. And then while it’s still wet, you put it into the camera and expose it. And then after the exposure, she takes it back into the darkroom and processes the plate, sort of like normal darkroom processing; you develop out the picture, and then you fix it with hypo.

CUNO: And the picture would be actual size? There’s no—

HELLMAN: Right.

CUNO: No way to increase the size of it or decrease the size of it? It is what it is.

HELLMAN: Yes, it is what it is. And that’s also the negative on glass, so it’s a very fragile object, in a way. And then she would take the negative and make positive prints from that, which she would print outside in the sun.

CUNO: Where would she get all the materials?

HELLMAN: You know, her initial camera was a gift, but she must’ve had connections. I know that once she became active, she was very kind of vocal and present in the photography realm, so she would’ve probably been able to purchase her own equipment from London, or someone would bring it to her, to the Isle of Wight. She was fairly well off, so she was able to afford a lot of equipment. She could ruin a lot of glass plates before she made a final image.

CUNO: Was it very uncommon for a woman to be doing photography at this time?

HELLMAN: Yes. Yes. Very. There had been women photographers from the very beginning, of course, and women who had run their own photographic studios; but it was uncommon for a woman to be considering herself as a photographic artist, or an artist at all, in Victorian society at this time. She was certainly breaking rules, in terms of presenting herself alongside male artists.

CUNO: In the text that Virginia Woolf wrote, she said that the camera gave her, “at last, an outlet for the energies that she had dissipated in poetry and fiction, in doing up houses, in concocting curries, and entertaining her friends.

HELLMAN: Mm-hm.

CUNO: You don’t get a sense, in this text from Woolf, that she appreciated the character of not only Julia Margaret Cameron herself, her great aunt, but the quality and nature of the kind of culture they lived at the time, in the High Victorian period.

HELLMAN: Yeah. I also like how Virginia Woolf mentions that Julia Margaret Cameron also inherited from her mother, a love of beauty and a disdain for English conventions. So I think she carried that through into her photographs then.

CUNO: We also know that Cameron turned her family cottages there in the Isle of Wight into a kind of a stage set, and that she had friends and family members taking roles. She had painters, like George Frederic Watts; she had her goddaughter, named Julia Jackson, who was a favorite model for other painters; Holman Hunt and Burne-Jones; the actress Ellen Terry; and the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson. Tennyson, I think, had a house on the Isle of Wight, as well.

HELLMAN: Mm-hm. Yeah, he was her neighbor, yeah.

CUNO: So what was the entertainment life like? They present these idylls or these kind of theatrical activities, as a serious entertainment? Or as a kind of just goofy entertainment?

HELLMAN: I think it was a mix of both. Certainly, for her friends and family, it was entertainment. And she, you know, set up this theater for the young people, when they visited, to create plays. And the adults would watch. And there was a real kind of playful energy to it. But then when she was making her photographs, she set up similar sets or stages and posed her models, but she took it very seriously. At least what I sort of gather from what I’ve read about posing for Julia Margaret Cameron, it was not a fun enterprise.

CUNO: Right.

HELLMAN: Maybe the sets themselves and the theatricalness behind it was very fitting for Victorian sort of love of dress-up and play acting and creating characters, for Cameron, it was about making artwork.

CUNO: So if she were in London, would she likely do the same kind of thing? Or was this something that one did in the countryside?

HELLMAN: Oh, that’s a good question. I think she would have found a way in London to do the same thing. She did, though, on the Isle of Wight, she had the space and the outdoors. She turned the henhouse into the darkroom, and then another house into her studio. And so she had the space and the time and the kind of landscape to create these in some ways, fantastical photographs.

CUNO: Were these theatrical events interesting in and of themselves, and then they were photographed? Or were they set up to be photographed?

HELLMAN: I think she set them up to be photographed. But they were based on other paintings or scenes from plays that she knew about or that her friends had written. They were, definitely would’ve been, many of them at least, scenes and characters that Victorian audiences would recognize from literature and plays and—

CUNO: Is there a body of work of other photographers, of this kind?

HELLMAN: There is. Not quite the same, but we could look at the work of Oscar Gustave Rejlander, who was in fact, apparently one of her mentors in the process. He visited her on the Isle of Wight. Supposedly, he taught her some of the photographic process. So they were actually friends, and Cameron was certainly inspired by him in some ways to create these staged scenes.

CUNO: Mm-hm. So that she had some international friends. I know that she also sent her photographs off to Berlin and elsewhere on the continent. So to what extent was she engaged in a community of photographers, as opposed to a community of poets and playwrights and actors and actresses and musicians, there on the Isle of Wight. I mean, she had an international reach and she had professional— or maybe not professional, but a serious relationship with a range of photographers.

HELLMAN: Mm-hm. Within a year of taking up the camera that she was gifted, she was sending her photographs off to not only the London Photographic Society, but also to Scotland and to Berlin, to be entered into these exhibitions that the various photographic societies would host. And she was disappointed when she didn’t receive a medal. She was very concerned with making money from her photographs and wanting to be recognized for her work as a photographer.

She copyrighted several of her photographs right away in 1865. She was very sort of forward thinking, in terms of how she wanted her photographs to be received and seen and recorded for the future. She was, it seems personally, she was just a real force.

CUNO: ’Cause this is just thirty years or so after the founding of photography, the discovery of photography, right?

HELLMAN: [over Cuno] Right.

CUNO: And you described, these photographic portraits that people had taken of their friends and family, and they’d exhibit them in their house. But there’s quite a leap from that kind of activity to the kind of artistic international realm of activities that she was involved in so quickly—in her case, less than a decade after being given a camera.

HELLMAN: Right.

CUNO: How was that possible? Was it just because people were so curious about photography that it elevated everybody quickly to some stature, level of stature?

HELLMAN: Well, it’s a good question. I think she really made it happen. I think she was very individual. She had a very individual style and a very specific idea of how she wanted to make her photographs. And this was this very new thing for photography at the time, because even though Rejlander was making stage scenes that were quite inventive and other photographers were making staged photographs, there was less of a kind of willingness to honor an artistic photographer in the 1860s.

Photography was still considered a mechanical medium that was made by a machine that was certainly good commercially, because you could make photographic portraits. But it was a challenge for photographers to present themselves as artists. So she was among these very sort of few photographers that you could say— Artists like Gustave Le Gray in France in the 1850s; Nadar, certainly, in the 1850s.

There were these kind of few photographers that really forced themselves, or presented themselves, as artists. And it was really because they had a very particular way of creating photographic images. But it was— it was a very rare thing for photography at the time. She was certainly forging a path that hadn’t been forged yet.

CUNO: You describe the quality or the appearance of the photographs that she made, how rich and deep were the colors of the photographs, browns and gold and amber colors.

HELLMAN: Yes. So this is pre color photography and the tonality would come both from the negative itself— The glass negative held that syrupy liquid with the sensitized image on it. And then when it was exposed to the albumen paper, albumen paper had a kind of dark brown, even sometimes purplish quality to it. It was not black and white like we think about today, but really a kind of rich brown.

And because she was so creative in the darkroom and with her printing, her prints are actually— they vary in tone and color, because she was trying all different kinds of things, in terms of exposure and length of printing. So the tones of her photographs actually range from a kind of lighter brown to a darker brown, a richer—

CUNO: And does that depend on the amount and application of chemistry?

HELLMAN: It’s a combination, certainly, with how dense the negative that she created was. So how much contrast was in the original negative. And then the print itself, how long she left it out to be exposed in the sun and how much light was exposed onto the paper.

So there’s a real range, in terms of what you could do with photography. And she really explored that. I think that’s also why she’s so interesting, ’cause she didn’t stick to the same thing every time.

CUNO: You mean we had the same photograph, that is the same subject, and printed differently, so you can see a range of options or ways she was exploring the printing?

HELLMAN: Mm-hm. Mm-hm. And she very famous for allowing mistakes to become part of the final image. So if there happened to be a crack in the negative or a slight difference in tone in the paper, she would let that stay. Even spots. She said, “Let the spots remain,” because she liked the quality of showing the process and showing this kind of living process of photography.

CUNO: Was that in part, do you think, because she was answering the criticism that photography was a mechanical medium, and so she was playing with it? She was developing it as if it were an ink drawing of some kind?

HELLMAN: Mm-hm. Yeah, it’s ironic because she was answering that claim and sort of fighting against that insistence by many that photography be solely mechanical.

But at the same time, it was really the photographers that criticized her. In the photographic societies, she was just too far ahead of her time. They were not ready to see a photographer, let alone a woman photographer, making mistakes, or making less focused images, and claiming them as artwork.

The photographic societies of the time were very focused on focused images. They believed that even artistic photographs had to be fully delineated and clear images. And she was going against that.

CUNO: I know the descriptions of her coming out of the henhouse or wherever it was she did her printing, and making her way to the house, and her clothes would be covered with the remains of chemicals that she’d been—

HELLMAN: Yeah.

CUNO: It must’ve been dangerous.

HELLMAN: Yes. I mean, the daguerreotype process was much more dangerous, but the chemicals were not good to your skin. And you know, she is described as having these stains on her fingers and she would ruin the dining room linen because her— when she ran in to bring her negatives to show her husband, she would drip the chemistry all over the linen.

But that didn’t stop her, of course. If anything, I think she seemed to like the process and liked to show that she was working with it and literally had it on her hands.

CUNO: So I’m imagining three different sort of categories of photographs for her. One is these photographs of staged theatricals, in which she has people pose in relationships to each other, but that would be recognizable as from a particular scene of a particular play or from a part of a poem by Tennyson or something. But anyway, there was a kind of artificiality to it.

HELLMAN: Mm-hm.

CUNO: Then there was a kind of staged literary photograph. Like a portrait, but somehow enhanced and— such that it would lend you to think about— The person being photographed might be a character of one of the plays, maybe stepped out of those plays. And they’re even identified, so that one time, May Prinsep is photographed as Beatrice Cenci, the Florentine heroine of a play by Shelley.

So she has photographs of the major figures of her day—Darwin, Tennyson, Herschel, all these others. Are those kind of three principal ones? And if so, is that a broad range of photographic types or subject matter?

HELLMAN: When she sent off her photographs to exhibitions, she would actually send them in these three categories. The ones that she staged, dressed up both her maidservants and her relatives, into characters from plays, she called these fancy subjects. The Beatrice photograph of May Prinsep— May Prinsep was her niece, and a frequent model of hers. She often transformed these young women into these tragic female heroines like Beatrice and others. And she seemed to go back to that theme quite often, the tragic female character.

CUNO: Is it too tempting to think there’s some biographical relationship to that theme? Or is it just that was the kind of aesthetic of aesthetic of the day?

HELLMAN: You know, she had— as much as she had an incredible life, she was this— I mean, and this might be a stretch to say, but she had six sisters that were all deemed very beautiful, and she was the non-beautiful sister of her family. So she may have seen herself as the kind of tragic outlier. But it doesn’t seem to have bothered her, because she was so forceful and proud of her own artwork. She was deemed the sort of talented sister, out of the other beautiful ones.

CUNO: You began to talk earlier in this podcast, about the difficulty of posing for her, and that the literary evidence of that—that is, the remarks that people leave behind as to how it was they were posed by her and the time it took to take the photographs. And Tristan Powell, in the introduction to the Getty-published book, quotes a sitter of Julia Margaret Cameron’s, recalling her experience sitting for a portrait. She says, “The studio, I remember, was very untidy and very uncomfortable. Mrs. Cameron put a crown on my head and posed me as the heroic queen. This was somewhat tedious, but not so half bad as the exposure.

“Mrs. Cameron warned me before it commenced that it would take a long time, adding with sort of a half groan, that it was the sole difficulty she had to contend with in working with large plates. The exposure began. A minute went over and I felt as if I must scream. Another minute and the sensation was as if my eyes were coming out of my head. A third, and the back of my neck appeared to be afflicted with palsy. A fourth, and the crown, which was too large, began to slip down my forehead.

“A fifth— But here, I utterly broke down, for Mr. Cameron, who was very aged and had unconquerable bits of hilarity which always came in the wrong places, began to laugh audibly. And this was too much for my self-possession, and I was obliged to join him.”

HELLMAN: Yes. She’s not described as a very nice or gentle photographer. She was very demanding and she didn’t care for using any of this normal portraiture support systems, like the vice to hold your head up or even something to lay your elbow on. She was very insistent that they only use the props that she required and they had to suffer.

CUNO: [over Hellman] And how long would a shoot take for a photograph, a single photograph?

HELLMAN: So apparently, about three to seven minutes. So they had to sit still for between three and seven minutes, and stare into the lens for that length of time.

CUNO: [over Hellman] And if there was a certain feeling that they had to have or to express, because it was a staged photograph, they had to continue that— expressing that certain feeling for three to seven minutes.

HELLMAN: Right. And if they moved or if they, you know, started laughing like this sitter, the image was ruined and they had to start over again. So there was a lot of incentive to keep still, ’cause she wasn’t going to let you go. But that’s also why she was able to create as much as she did create in her career. She was very determined.

I also like Woolf’s description where Virginia Woolf said, “She cared nothing for the miseries of her sitters, nor for their rank. The carpenter and the Crown Prince of Prussia alike must sit as still as stones in attitudes she chooses, in the drapery she arranged, for as long as she wished.” And I like that idea that it didn’t matter who they were. Whether they were the, you know, Crown Prince of Prussia or the local carpenter, they were treated the same in her studio.

CUNO: Yeah. So Virginia Woolf— And you described her earlier as being less than respectful of the Victorian era and the aesthetic sensibilities of that era. Now, Roger Fry’s a very different guy. And he comes along and is published in the same publication as Virginia Woolf, published by Virginia Woolf’s publishing house. And his response to Cameron’s work is quite different.

His goal as a critic was to consider the artistry of Cameron as a photographer—I mean, the body of work—and he did so by referring to specific plates or photographs, almost as if he were talking about specific drawings by an artist or paintings by an artist, and by developing a critical framework for photography itself, which he found in the greatest works of art. And he found it to be representative of a cultural period, as he said it, which turned on, focused on beauty.

He referred to this with regard to The Rosebud Garden of Girls, a title taken from Tennyson’s Come Into the Garden, Maude. Can you describe that photograph for us?

HELLMAN: Mm-hm. Yes. The Rosebud Garden of Girls was taken in June, 1868. It depicts four women closely huddled together in front of a leafy hedge. They wear these long flowing white robes and they’ve let their long Victorian hair flow down. Each looks in a slightly different direction, with a very kind of serious stare.

And each holds flowers or branches in their hands. The models are actually all sisters; they’re daughters of a friend of Cameron’s brother-in-law. But here they’re transformed in this—I guess as the title suggests—a rosebud garden of girls. And it’s a very kind of dreamlike, wispy sort of image. The fabrics of their gowns kind of blend together and their hands are positioned so they kind of make a rhythmic dance through the frame.

It’s quite a beautiful image and I can understand why Fry accepted it as an image. I think he said something about he did not really like her group photographs, but this one could pass as an aesthetic image.

CUNO: He wrote of it, I think, that he saw it as “a walled-in garden of solid respectability, sheltered by its rigid sexual morality by the storms of passion.”

HELLMAN: Mm-hm.

CUNO: There was a kind of an innocence to these.

HELLMAN: Yeah.

CUNO: And a kind of coordinated or harmonic innocence, as you said, in which each of the four sitters, each of the four young girls, have a kind of innocent relationship that plays one from another.

HELLMAN: Mm-hm. Yeah. He places it, he says its definitely a Pre-Raphaelite picture and places her in a time in England when the artistic circles were very interested in the idea of creating these beautiful images that had a kind of luminous palette and moralizing subject matter. So he’s fitting her into that artistic realm. Which was also giving her quite a status as a photographer.

CUNO: Yeah. And he says that the portrait of Thomas Carlyle, which he praised saying, “Neither Whistler nor Watts,” the two painters, “come near to this in the breadth of the conception, in the logic of the plastic evocations, and neither approaches the poignancy of this revelation of character.” There’s a kind of serious critical response to these photographs, of a kind that Fry would later give to Cézanne, for example.

So there’s a kind of consideration of them as being elevated to the status of art. If there’s any questions about the mechanical limitations of photography, it was her sensibility that was somehow made palpable by the photographs that she took.

HELLMAN: Yes. Yeah, he definitely took her seriously. I think she would’ve been happy about that, because he was treating her photographs, like he did with paintings, as very in terms of form and the way that the form could express something of the character or the subject; and that she was, just like a master painter, able to convey that and to express something through the form within her images.

So her portraits, he picks up on, particularly because they are evidence of this ability that she has to convey some kind of broader, bigger expression than just a exterior of a person. She really kind of captures this personality of Thomas Carlyle or Herschel or Tennyson, and renders them as artists and kind of these great artistic minds.

CUNO: Was that a quality about her work that was seen by others, and set her apart from other portrait photographers?

HELLMAN: Yes. When she was not criticized, she was praised for the kind of— the way that she could elicit the kind of soul of the person she was photographing, rather than just the exterior face of physiognomic portrait. So she was praised for that. Mostly by artists, though, not by photographers.

And so it won’t be until much later, and certainly with Fry in 1926, that she’s recognized for that quality. And there are other photographers, like Nadar, who’s also interested in that same problem.

CUNO: Yeah, I was sort of thinking of the portrait of George Sand by Nadar.

00:40:26:20 HELLMAN: Yeah. Right. Yes.

CUNO: Which is maybe a decade earlier or so?

HELLMAN: Yeah, it’s—

CUNO: But it has the same sense of presence about it, because George Sand herself had that sense of presence. But it was something that the camera didn’t diminish, but enhanced.

HELLMAN: Mm-hm. Yeah. They are similar, in a sense, that they both position their sitters in very shallow spaces and had very plain backdrops and few props, so that the photograph was really just of the sitter.

Both Cameron and Nadar were kind of masters of lighting their subject. In their studios, they could bring the subject out from the background, so as if they were kind of a sculptural presence coming out of the image. So they were similar in that way, and they both believed in making a portrait that showed more of the inner character of a person on the exterior, rather than just an exterior portrait.

CUNO: I was wanting to place her between Nadar and Stieglitz, Nadar being from the 1850s or so and Stieglitz being in the 1920s, and Cameron being in the 1870s or so, right in the middle of the two. She didn’t, I suppose, know the photography of Nadar. But if she had known and been influenced by it, was it in turn that she influenced anyone after her, like Stieglitz or anyone?

HELLMAN: She was influential, certainly on P.H. Emerson, who was then an influence on Stieglitz. So she does get her recognition more towards the end, the turn of the century, when the Pictorialist photography movement comes to the fore. And that’s really with the efforts of Stieglitz, making photographs that were self-evident as artworks.

And one of the reasons they were self-evident as artworks was because they had this kind of painterly quality to them. And Julia Margaret Cameron would’ve been cited as one of these examples or precursors to that, because she certainly made photographs that had the impression of being like the paintings of her time.

But it’s interesting to compare her portraits with Stieglitz’s portraits of O’Keeffe, because there is a similarity there in the kind of intimacy with the subject, this immediateness of the subject, both in Cameron’s sitters and in O’Keeffe. This idea that she’s really present and kind of emerging from the frame, rather than being kind of pressed back into it.

CUNO: Mm-hm. Now, Cameron, as we mentioned earlier in the podcast, left her own account of her photography, as fragmentary as it was. She writes this book, The Annals of My Glass House, in 1874. And it’s not published for another fifteen years, till 1889, and that’s ten years after her death. And it’s a rather straightforward account of her career as a photographer. It doesn’t read as beautifully as— or with any kind of the individual character of a Virginia Woolf, or the kind of intelligence and perceptive analysis of a Roger Fry; but still, it’s her talking about it.

And she describes her first photograph as a portrait of a farmer. And then she describes how she turned the henhouse into a darkroom and so forth. Then she begins noting that her photographs have traveled all over the world. And this is only ten years after she started photography. And Europe, America, even Australia. And she said, “It was met with a welcome, which has given it confidence and power.”

Was she peculiar in that sense? It wasn’t common for photographers to have that kind of reach so quickly?

HELLMAN: Yes. She was definitely peculiar, certainly as a woman photographer. And you can get from that, her description, you can gather that she doesn’t lack the confidence or ambition that was required to kind of send her work out so soon after she started making it.

You know, without waiting for confirmation from the photographic society or any kind of affirmation of her values, she really took it upon herself to create that market for herself. And it was well-received. It’s ironic, you know, that she was given medals in Berlin and other places, but it was the British Photographic Society that took the longest to kind of give her praise.

CUNO: She said that she already had sent photographs to Scotland as early as 1865. [Hellman: Yeah] So within a year of getting a camera. And she had written a novel or two novels. I mean, she had a kinda literary sense to her, as well.

HELLMAN: Mm-hm, mm.

CUNO: Even though Virginia Woolf didn’t think much of that literary sense.

HELLMAN: No. She didn’t.

CUNO: But what did she expect of this—

HELLMAN: It’s not where Virginia Woolf got her…

CUNO: No, exactly.

HELLMAN: …writing skill.

CUNO: What did she expect of this book that she left abandoned? Did she expect it to be, I mean, of interest to people?

HELLMAN: She did. In writing this Annals of My Glass House, I think she did really envision it as a kind of companion to her artwork, as a sort of her voice over her photographs. That somehow she could realize that it was important in the future to have some sort of record of what she thought of her work and how she wanted her photographs to be seen.

It’s pretty remarkable, when you think about it, because it’s so early for a photographer to be that assertive and confident about her work. And if we didn’t have this record of her, we would lose quite a bit of our sense of how she thought of herself. And I think, you know, that’s a very important thing when you’re thinking about artists and thinking about them as individuals and what it meant to be an artist, in their mind.

CUNO: So the book was published in the eighties, late eighties, ten years later. What was the reception of the book?

HELLMAN: By that time, we had the photographers like P.H. Emerson and many more photographers advocating for the soft-focus photograph. So by that time, it was well received and she was being picked up by Stieglitz’s circle and honored by these turn of the century photographers, as a precursor.

And the there is again, a kind of span of time there where her recognition decreases because she’s being sort of superseded by the interest in modern photography and early twentieth century straight photography and things like that. So she comes back sort of later into photographic criticism with Helmut Gernsheim, in 1948; and then later in the 1970s, when the market for her photographs returns, and for nineteenth century photographs.

CUNO: So what is her status now?

HELLMAN: So now, she’s considered pretty much one of the best photographers of all time, certainly one of the top nineteenth century photographers. And she’s known as a breaker of rules, sort of someone who broke the rules of photography before there were many rules for photography, and kind of carved her own independent path, before there was the kind of permission for photographers to have that recognition.

CUNO: Now, this— these three texts, the Virginia Woolf and the Roger Fry and the Julia Margaret Cameron, are part of a little book that’s in a series of Lives of the Artists that we’ve been producing here at the Getty, again through Getty Publications. But I know that the Getty has a strong and large collection of Cameron. Could you describe that for us?

HELLMAN: Yeah. We’re very lucky to have a large collection that was acquired in the 1980s, when the department of photographs was founded. We have over 200 photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron. And they range from her fancy subjects to her portraits. They range from the large-scale sort of larger plate size to the smaller sizes. So we have a real breadth of her work.

CUNO: And I know that we’ve published a sort of catalogue raisonné of the work and we’ve had exhibitions of the work.

HELLMAN: We published— One of the first kind of catalogue raisonnés, you could say, of a photographer was the complete photographs of Julia Margaret Cameron that the Getty published. And that still continues to be a source for researchers, and a kind of guide to her work.

So yeah, we’ve used the collection that the museum has and done our part, in terms of making her photographs known. She doesn’t need a lot of help, though, ’cause I think people kind of gravitate towards her photographs naturally. There’s the kind of presence to them that speaks to people today.

CUNO: Well, now, she leaves England with her family, or at least some members of the family. Some of her sons, preceded her to Ceylon, so Sri Lanka. And so she and her husband now to go Sri Lanka. They live out their last years there. And she makes photographs until she dies, or within months of her death. So for four or five years, she makes additional photographs. Are they markedly different? Because of course, the people are different, the setting is different, her age is different.

HELLMAN: Yeah, it’s a good question. She does keep making photographs. Only about thirty, or less than thirty, are known today, so it’s hard to give a full sense of everything she was making. But they are similar to what she was making on the Isle of Wight, but just different models. So she’s still making these kind of ethereal, dreamlike portraits, but she’s using the local children or people around the house. Any visitor who happens to come by gets put into a costume and photographed. But they’re really the same kind of compositions. At least in the ones that I’ve seen.

CUNO: So she dies in 1879, and her husband predeceases her by a few years, and they’re buried side-by-side in Sri Lanka. It’s a kind of perfect conclusion to a fantastic life.

HELLMAN: Yeah. Right, I know. Yeah. She really did have a fantastic life, and her photographs certainly continue to.

CUNO: Well, it’s a fantastic book and, of course, an extraordinary life, so Karen, thank you so much for joining me in this podcast. It was great to be here with you.

HELLMAN: It was a real pleasure. Thank you.

CUNO: Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, President of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art & Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

KAREN HELLMAN: I think people kind of gravitate towards her photographs naturally. There’s...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Virginia Woolf was not Julia Cameron’s great-aunt, as it says in the introduction. Rather, Julia Cameron was Virginia Woolf’s great-aunt.

Thanks for pointing out the mix-up! We’ve made the correction.