Subscribe to Art + Ideas:

“Berengario’s books show animated cadavers and skeletons set in a landscape, often so animated that they’re displaying their own dissecting bodies to the viewer.”

For centuries, doctors and artists have relied on renderings of the human body for their training. Until the Renaissance, anatomy studies were primarily textual, but in the late 15th and early 16th centuries illustrated anatomy books began to be published in greater numbers. Macabre prints of flayed bodies painstakingly depicted muscles, veins, and nerves, and allowed for a far better understanding of the human form. In the 19th and 20th centuries, anatomy studies were also targeted to general audiences, and moralizing flap books with Christian themes, children’s toys with removable body parts, and wax models for museum exhibitions gained popularity. The Getty Research Institute exhibition Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy explores this long history of illustrating the body.

In this episode, scholar and independent curator Monique Kornell, GRI curator of prints and drawings Naoko Takahatake, and GRI research associate Thisbe Gensler survey this history. They move from the 16th century books by anatomist Andreas Vesalius to contemporary artworks by Robert Rauschenberg and Tavares Strachan, explaining the relevance of anatomy studies across time.

More to explore:

Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy explore the exhibition

Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy buy the book

Transcript

Jim Cuno: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

Monique Kornell: Berengario’s books show animated cadavers and skeletons set in a landscape, often so animated that they’re displaying their own dissecting bodies to the viewer.

Cuno: In this episode, I speak with Monique Kornell, Naoko Takahatake, and Thisbe Gensler about their exhibition Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy.

Renderings of the human body have been crucial tools for both artists and doctors for centuries. Anatomy was a core element of artistic training, and artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were praised for their skill in depicting the human form. But there was also a wide market for anatomical drawings among doctors and medical practitioners as tools for teaching and study.

The Getty Research Institute exhibition Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy showcases innovative representations of the human body from the 16th century through the present day, from anatomists like Andreas Vesalius to artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Tavares Strachan.

I recently spoke with scholar and independent curator Monique Kornell, GRI curator of prints and drawings Naoko Takahatake, and GRI research associate Thisbe Gensler in the galleries.

Thank you, Monique and Thisbe and Naoko, for speaking with me on this podcast episode this morning. Now, Monique, Andreas Vesalius’ influential anatomy book The Fabrica—or the fabric—of the Human Body dates to 1543. It’s not the earliest book to feature anatomical illustration. What was the earliest book, and why has the Getty Research Institute collected anatomical books and prints, anyway?

Kornell: So while the GRI’s collecting scope is wide-ranging, you may be forgiven for wondering why a library focused on art has such significant holdings in anatomy. Well, anatomy truly belongs in the library because it was one of the key subjects taught to artists for hundreds of years, being part of the curriculum of early art academies, which were first instituted in the late 16th century.

So from the Renaissance onwards, artists sought out the study of anatomy, turning to doctors to observe dissections, or picking up the dissection knife themselves, or drawing from articulated skeletons set in lifelike poses, such as we see in Cornelius Cort’s engraving of an ideal art academy, after Stradanus, from 1578.

Some anatomy books made their way into the collection through the acquisition of general collections of art books. Some anatomy atlases were purchased as significant examples in the history of book and of book illustration. Other books are representative of the production of well-known artists, such as the set of illustrations of the nerves, after drawings dated to the early career of the Roman 17th century artist Pietra da Cortona.

Up until the Renaissance, the anatomy of the body was described primarily in words, rather than images. The earliest academic anatomy text with significant illustration is that of the Bolognese surgeon and anatomist Berengario da Carpi. His commentary on Mundinus, a fourteenth dissecting manual, appeared in 1521. And then he came out the next year, with a short introduction to anatomy, in 1522, and the GRI owns a copy of the second edition, of 1523.

And these books were influential in many ways. Rather than showing the body inert on a dissecting table, Berengario’s books show animated cadavers and skeletons set in a landscape, often so animated that they’re displaying their own dissecting bodies to the viewer. Berengario was constantly improving and updating his illustrations, which is unusual, that he would go to that expense. But he was well known as a connoisseur of art, a collector of art.

He once accepted a painting by Raphael in lieu of payment for his treatment of a Roman cardinal.

Cuno: Say that again. He accepted a painting by Raphael in lieu of payment?

Kornell: Yes. Yes.

Cuno: Oh, that’s extraordinary.

Kornell: It is extraordinary. He owned Antique sculpture, and he was a patron of the Renaissance goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini. So I think it is a case of anatomists who were interested in the visual arts, like Berengario da Carpi or Étienne de la Rivière, who was a coauthor of a mid-16th century French anatomy atlas and who— he himself also drew, and contributed to some of the illustrations, and Vesalius himself, who also drew and is responsible for some of his own illustrations.

Cuno: Now, what about William’s Cowper’s etchings of two flayed figures, in this book form that we’re looking at now? Cowper himself being equally renowned for his dexterity in dissecting as in drawing.

Kornell: The English surgeon and anatomist William Cowper provided the drawings for his own publications and that of his colleagues. He was famous in his own day for his skill in dissecting and as an anatomical draftsman. We are looking at the second edition of his Myotomia reformata, which was published in 1724. However, this is a posthumous publication. Cowper himself died in 1710.

Cuno: Do we know why he made the book in the first place?

Kornell: Yes. The Myotomia reformata is a book focusing on the muscles of the human body, and his aim was to show every muscle in the body.

What he’s done here is quite humorously posed them in choreographed poses, so they almost look that they’re reenacting a stage show. He’s showing the figures in two different layers, to make it easier for you to compare the muscles in each figure.

Cowper’s just one example of several anatomists in the exhibition who provided their own illustrations for their books, thus closing the gap between understanding and representation. Other examples are Étienne de la Rivière, from the mid-16th century; Jean-Galbert Salvage, who was an army surgeon, published an anatomy book for artists in the early 19th century; and from the mid-19th century, Don[?] Maclise’s Surgical Anatomy, published in London.

Cuno: So we’re looking at Étienne de la Rivière’s printed book of skeleton with nerves. Tell us about this.

Kornell: The surgeon and anatomist Étienne de la Rivière collaborated with physician Charles Estienne on the De dissection, which came out in 1545, in Paris. Étienne de la Rivière did the dissections, and also was responsible for some of the illustrations.

In this opening, a skeleton serves as a scaffold for springing nerves that are indicated by a jumble of criss-cross indicator lines. The skeleton is set in a landscape, and we see a port below. So he’s set in the land of the living. And he’s so animated that he is participating in his own display of his body, in the sense that he’s holding up his lower mandible to demonstrate the course of nerves that run through the lower jaw.

Cuno: Is this a particular ailment that is being addressed, or just a description of the anatomy?

Kornell: No, it’s purely for the nerves, and the course of the nerves. It appears to be a rather macabre to our eyes; but in fact, it is a scientific image.

Cuno: How do we know that they were accurate in their descriptions of the nerves and things then? Do we have them compared to now, that we can make that kind of judgment?

Kornell: I’m not a physician, but some people have analyzed them. You know, and you know, some parts are correct, some aren’t correct. That’s how it goes.

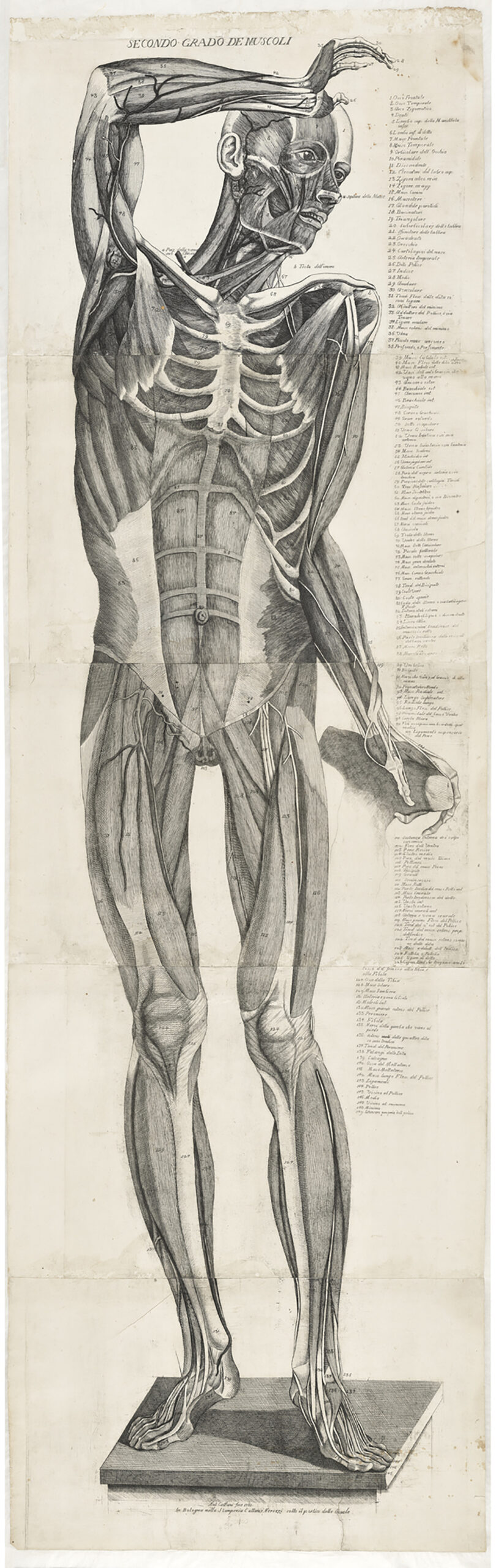

Cuno: [laughs] What about these three extraordinary figures by Antonio Cattani, printed in the late eighteenth century Bologna, I gather. It’s just one example, you say, of the anatomy of the body depicted on a one-to-one scale in this period. What purpose did this have, and how what it achieved that they could print so large?

Kornell: Well, this extraordinary and quite rare set of three life-size figures by Antonio Cattani, and dated to 1780 and 1781, were produced in Bologna by Cattani, who specialized in anatomical prints. And their life size was achieved by joining five prints each together. And they were part of Cattani’s plan to show the entire course of anatomy of the human body in print.

And they were originally marketed to artists, but by 1780, Cattani and his partner, Nerozzi, had moved their shop nearby the Bologna anatomy school. So medical students passing by could purchase these.

Cuno: Were they expensive? Could an anatomy student actually afford to buy such a thing?

Kornell: I’m assuming that they could, because it’s marketed initially to artists, and then probably purchased by doctors. So the Cattani figures are emblematic of a vogue for depicting the anatomy of [the] body in actual size. And this happened in sculpture and print. It was a physically astonishing way of conveying the body structure, allowing for greater detail, and for some, representing a true imitation of nature.

Cattani himself modeled his figures on sculptures, anatomical sculptures by Ercole Lelli, a sculptor and artist of a generation before Cattani. And it’s notable that he retained the exact dimensions of these sculptures. Two of the figures are after caryatids that supported the baldachin above the lecturer’s seat in the Bologna anatomy theater. And one figure is after a life-size wax anatomy in the Bologna Institute of Sciences.

Cattani would’ve been also aware of life-size écorché models popular in art academies, such as those by the French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon.

Cuno: Tell us what an écorché model is.

Kornell: Oh, an écorché model was a sculptural figure showing the muscles of the body with the skin removed.

Cuno: What does écorché mean? Is that what it means?

Kornell: It means flayed. It does, yeah. And oh, the life-size impulse also made for particularly large and unwieldy and expensive anatomy books. Govard Bidloo, in his Anatomia Humani Corporis, asked his artist, Gerard de Lairesse, as far as possible, to portray the figures in proper size and from the life.

Cuno: Naoko, why was Bologna a center of printmaking and the study of anatomy?

Naoko Takahatake: Anatomical illustration was a pan-European phenomenon through the early modern period. And certain cities emerged as important centers of production over the centuries, including Bologna. And there are a number of factors that contributed to this. Already in the thirteenth century, Bologna established itself as a major center for the study of medicine.

In the fifteenth century, Bologna permitted public dissection. And in 1540, Vesalius, the author of the Fabrica, performed his own dissections in Bologna, as he had done in other cities.

The experience of performing dissection shaped Vesalius’ approach to and view of the study of anatomy, away from a strict reliance on text, especially those of the ancients, to learning from the body, from dissection. Vesalius did not publish his Fabrica in Bologna, but the city did issue a number of landmark publications in the 16th and 17th centuries, including Berengario da Carpi’s Short Introduction to Anatomy, Ruini’s Anatomy of the Horse, and in the 17th century, Domenico Bonaveri’s Notomie di Titiano, which was geared toward artists. All of this publication was possible because Bologna had a robust publishing industry and produced very high-quality, lavishly-illustrated books in the service of and fueled by the needs of the university.

There are also artistic considerations to acknowledge, including the fact that Bologna was home to a number of artist academies, including the celebrated Carracci Academy, which was founded in 1582 and which included the study of anatomy in the education and training of young artists. And Bologna was also home to an important school of printmaking, which included figures like Agostino Carracci. And so all of these traditions are coming together and contributing to the possibility of an ambitious project like these life-size figures by Cattani to be produced.

And I would say that in many respects, Cattani’s prints are a celebration of the vitality of anatomical study within the fabric of Bolognese society. In his selection of models, he chooses two of these sculptural figures that adored the anatomy theater in the Archiginnasio, which is in the very center of the city of Bologna.

Cuno: Yeah. And how many were there originally? Now we’re looking at three here; were there more than this?

Takahatake: They were conceived as two pairs. And as Monique has discovered, in the subscription notice announcing the publication of these full-size figures, there were initially four prints that were intended: two écorché figures showing the muscles front and back, which we have here; and two skeletal figures, front and back, although the posterior view of the skeletal figure is not known.

Monique mentioned that these prints are extremely rare, and there is an inverse rate of survival between, I would say, scale and survival. That is to say, the larger the print, the less likely it is to survive because they’re harder to store. But there is also the function to take into consideration. These prints would have been made to be displayed, and so they were likely also consumed through use.

Cuno: Would they be visible from the street or only within the theater?

Takahatake: Well, that’s an interesting question because on one hand, the figures are rendered in a way that they can be viewed from a distance, but the details, the numbers that are keyed to the index, are impossible to read from a distance. So these require both viewing from close and from afar.

Cuno: Yeah. Now, we’re looking at a life-size dissected image of a woman in a colored mezzotint, something which is kind of laborious to make but lends itself to a kind of more convincing rendering of the body, I should think. Naoko, tell us about this.

Takahatake: The single-sheet prints and illustrations, book illustrations in this exhibition and the catalog are predominantly in black and white. But color played an important role in the history of anatomical illustration.

When color was used, it was not strictly with the intent to more accurately render interior views of the body to increase naturalism or veracity. One important role of color was to increase the legibility or clarity of an image. Crucially, color could help differentiate between structures of the body. And certain conventions were evolved and broadly adopted, such as the use of blue and red to distinguish between the networks of veins and arteries. An example in this exhibition is the painstakingly hand-colored figure showing muscles, veins, and arteries, by Serantoni, in Mascagni’s Anatomia universale of 1833.

Color was also used to emphasize the difference between bone and muscle in the depiction of the skull with the muscles of the neck, in a publication by Giuseppe Delmedico. Here, the color is printed. A single plate was inked using two different colors, black and red, to distinguish between the bone and the muscle. Not all copies of Delmedico’s publication were issued with color. And this is an important reminder that the use of color, whether hand-applied or printed, represented an additional expense and additional labor.

Returning now to Dagoty, who is the perhaps most well-known figure in the history of color anatomical illustration, the color printing technology that Dagoty is using, color mezzotint, was developed a generation earlier by Le Blon. And it involves printing from multiple plates, each plate inked in a different color—the primary colors, blue, yellow, and red, plus black.

And the superimposed printing of those translucent layers of ink on paper would optically blend to create additional colors and hues. Mezzotint is a technique that allows for very subtle gradations of tone. And the overall effect is, therefore, very painterly. Dagoty’s color anatomical illustrations were immensely successful and drew much attention by dint of their remarkable coloristic effects. But the scientific accuracy of his images were a matter of great debate.

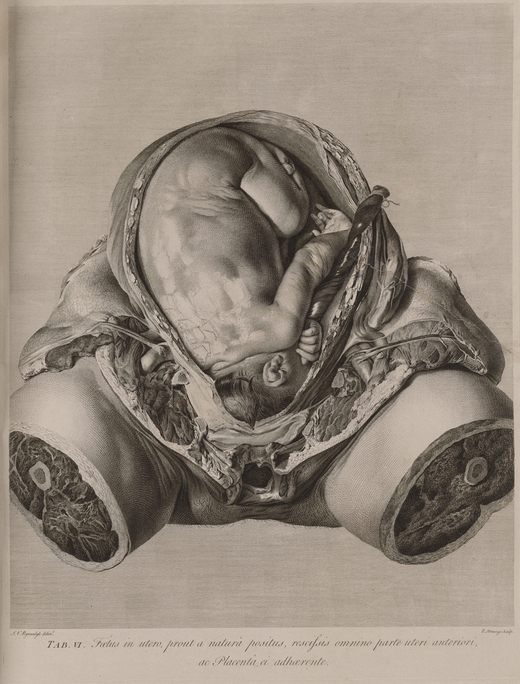

Cuno: We’re looking at a woman whose body has been opened to us so that we can see the interior of the body and the organs that are necessary to produce the life-like effects of this print. Thisbe, what about pregnant women?

Thisbe Gensler: Well actually in this exhibition there is a wonderful juxtaposition of Dagoty’s life-size color dissected woman and William Hunter’s Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus. This is an incredibly gruesome image that many visitors might find quite brutal and off-putting.

It does not do the idealizing, beautiful, coquettish look that Gautier Dagoty’s woman has. This is just the stumps of the leg, the torso completely sectioned off from the rest of the body, so that we just see the fetus in utero, with her skin and tissues pulled apart, so that we can see a nine-month fetus still in the womb.

This effort to create an incredibly naturalistic image. It is very life-like, there is the sheen of mucus on the umbilical cord, and kind of the wet hairs of the child’s head, its curled fingers—all these details that are giving us an extremely naturalistic look at a dead body. It is decidedly dead. It is not animated like Gautier Dagoty’s.

This is obviously on a dissection table, no longer living. We don’t have a face, we don’t have the rest of the body at all here. And part of the reason for that is a moment when male physicians were beginning to overtake a traditionally female domain of midwives in birth. And they’re doing so by invoking the language of science and anatomy to legitimize their kind of usurpation of this traditionally domestic experience.

So this kind of very Enlightenment objective and naturalistic image is also serving as kind of an advertisement for the male physician and the profession of obstetrics, which is just kind of coming into its own in this period.

Cuno: Does the book show different stages in the develop of the fetus?

Gensler: Yes. It shows all nine months of gestation. Each month is represented.

And it took Hunter decades to produce because cadavers of pregnant women were quite rare to come across, especially at each stage of gestation. As you can imagine, this kind of cadaver would take a while to acquire.

And this is very new. We hadn’t seen this level of morphology in obstetrical science. And we are seeing here a prioritization of the fetus over the maternal body. And that’s an interesting develop, especially when you look across this exhibition of other images of women’s bodies, which are, in the history of anatomical illustration, are typically portrayed in pregnancy, as an effort to describe reproductive health, rather than any other anatomical features.

Cuno: Now let’s move to the second gallery. Now we’ve entered into the second gallery of the exhibition, and we’re looking at a objects that represent the general sort of broad appeal to the general public, of anatomy. How is this demonstrated in the exhibition?

Gensler: I wanna actually even rewind to another overarching theme of this exhibition, which is the kind of Venn diagram of art and anatomy, which is often a circle. Or maybe a waning moon, but there’s a total eclipse in a lot of cases where, for example, the anatomist and the artist are the same person.

But we can think about this in terms of the consumption of these objects. And when we have artists and anatomists both, artists and physicians consuming the same textbooks, for example, or marketing surgical atlases to artists, as well— So there’s a kind of overlap in both the marketing and the consumption of many of these objects. And I think this also speaks in general to the very broad appeal of anatomy and the visual culture of anatomy, which over the centuries and across this entire exhibition, you can see.

So we spoke about the Gautier Dagoty and the popularity of these prints. It was an extremely commercial enterprise. It was a lucrative marketing opportunity to look at the body because so many people were interested in it.

Cuno: And these people were physicians, I guess, budding physicians.

Gensler: And lay people.

Cuno: The general public.

Gensler: Yeah. So physicians, lay people, artists. I hope that we will see that in this exhibition, that so many people are visiting this, because we’re all interested in our own bodies and looking inside them. And you know, we can see this in several examples across centuries in the show. Right now, we’re standing in front of Remmelin’s engraving, which is one of our fantastic examples of flap anatomies.

Cuno: Flap anatomies?

Gensler: Flap anatomies, yes. This is a technology, a paper technology, where you know, a paper support or flap can be lifted up and underneath it, you will see various layers of the body. And this anatomical print is full of symbolism that is not really in the scientific category, that would appeal to a general public. So moralizing themes and Christian and alchemical symbolism, and imperatives that are invoking self-reflection and contemplation of the glory of God through the study of anatomy and through one’s body, the fleetingness of life, and these kind of generalizing themes.

And this is a precursor to the golden age of flap anatomies in the nineteenth century, when you see—which we have some here—Witkowski’s color-printed flap book, as well.

Cuno: Tell us a bit more about the flap aspect of flap anatomy.

Gensler: Yeah, so these allowed a viewer to kind of do a virtual knifeless dissection. So without any of the gruesomeness of a real cadaver, you could see the various layers of the muscles, the bones, the organs, different parts of the body in finer detail.

Cuno: By lifting up a flap.

Gensler: Exactly.

Cuno: You’re literally lifting up a flap.

Gensler: You’re literally lifting up a flap. And this one is an incredibly intricate one, which I will let Naoko speak a little more about.

Cuno: Naoko?

Takahatake: We’re looking here at Remmelin’s microcosmic mirror in the edition of 1619. It contains three intricately detailed flap anatomies. This one shows a standing woman with her foot on a skull. And two sets of flaps open up like saloon doors, to expose the interior of her chest and her abdomen. Concealed beneath the surfaces are multiple layers of paper flaps, each one illustrated with an organ or a physiological system.

The experience of lifting these flaps and uncovering what lies beneath simulated the process of a dissection, the gradual discovery and uncovering of the layers of the body. And these interactive works invited the viewer, the user to engage physically with the printed image.

Printed images were essential supports to all manner of scientific and humanistic inquiry. And with the introduction of flap anatomies and objects like them in the first half of the sixteenth century, prints moved from being mere repositories of information to being tools or instruments in the acquisition of knowledge. They represent a shift in modes of learning, from passive reading and viewing to more hands-on investigation and embodied experiences.

Gensler: This same imperative for a kind of tactile pedagogical mode is the same reason we have these life-size wax anatomies, which were kind of considered proxy cadavers. So when we think about a time before refrigeration, when a corpse would be rotting on the table and therefore limit your amount of time to study the body in a dissection, many different artists and anatomists made efforts to create more durable models that could simulate dissection and provide an opportunity for learning in, say, the summer months, when it was much too hot to be standing around a rotting body.

And returning to the general public theme, anatomy was a source of public fascination. We have, when you enter the exhibition, the wonderful graphic print, which is a blown-up image of the Leyden anatomy theater, which actually came from a tourist guide to the city of Leyden—which kind of testifies to the popularity and interest, that a tourist coming to city would wanna go to the anatomy theater.

And this is also true in the nineteenth century, of proliferation of anatomy museums, where a general public would go and see wax anatomies, from the heyday, really, of this in the eighteenth century in Italy. The Bolognese and Florentine wax anatomy workshops, which are very famous, and then to the UK, where there were tons of wax anatomy museums, which were not for specialists in any way. They were for general public. It cost a penny to go inside and see these. And there were public demonstrations of anatomy. So something like Smith’s manikin, which is here in gallery two, as well, which would accompany a public demonstration of anatomy. And this is something that in the nineteenth century public health reform movements, there were often accompanying models like this, which would show the ill effects of alcohol, or tight corsets even, on bodies, and were toured around in little cases like this, where they would do public lectures for a very, very general lay public, to encourage public health.

And I think the most pertinent example of that, very iconic one, is the Transparent Man, from the Dresden Hygiene Museum in Germany, where this was a life-sized clear plastic-encased anatomy, which had internal parts that would light up, and you could learn about each internal part. And it was a visualization of health, which was so popular that we eventually get these toy versions of it.

So this Visible Woman toy, which is from around 1960, is a plastic model assembly kit that was marketed to children, and ostensibly for kids to play with and learn from, but carries this legacy of public health that comes from early twentieth century plastic technology.

Cuno: Maybe we[?] should point out that printed on the surface of the top of the case is “from skin to skeleton, the wonders of the human body revealed. Assemble, remove, replace all organs.”

Gensler: Yeah, so that was another goal of many of these public health and hygiene campaigns, was to evoke wonder at the human body. Because there’s kind of notion of visualizing, with simplicity and clarity, the body, to evoke wonder and reflection, and to lead a healthier life.

Cuno: Now, you’ve described this 3D anatomical model for us, but tell us, what are the advantages of it over the flat two-dimensional?

Gensler: Right. So in addition to all the printed material, medical students and artists would also use three-dimensional models in their studies on both sides of that spectrum, from wax anatomies we’ve mentioned or écorché plastic figures, which artists would draw from, in addition to having a life model doing a pose that would activate the muscles in real life, rather than kind of the deflated postmortem plaster cast of certain muscles.

But in gallery two, we have a variety of examples of the ways that artists have tried to explain the complexity of the interior anatomy, which is hard to represent sometimes in 2D. And that is one of the advantages of these flap books; but we also have examples from the notion of transparency to x-ray, stereoscopic photography, color printing. And we see these developments over time in these various vitrines.

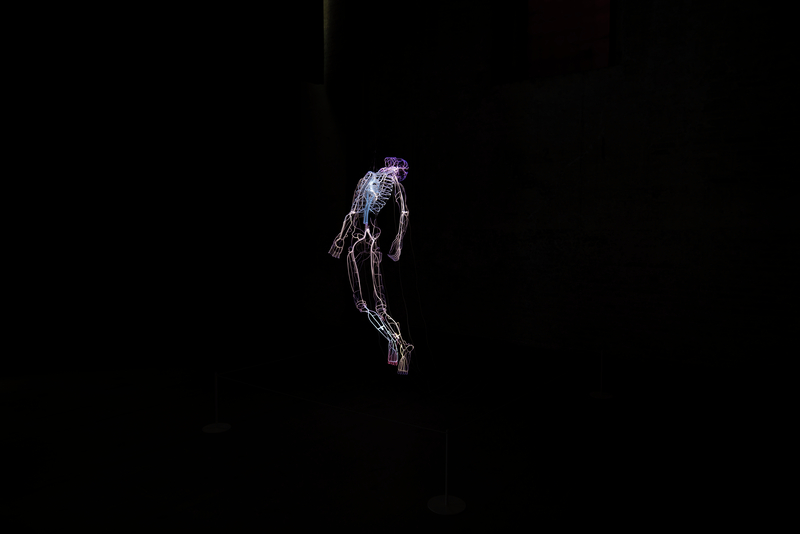

Cuno: Now the exhibition ends with works by Robert Rauschenberg and Tavares Strachan. Rauschenberg’s, a life-size lithograph of an x-ray of the artist’s entire body, references the booster rocket on the NASA launchpad; and Strachan’s is a life-sized anatomical neon light sculpture of Robert Henry Lawrence, Jr., the first African American astronaut. Thisbe, tell us about these works.

Gensler: As anatomy and the study of anatomy in artistic education wanes in the twentieth century, it is no longer a priority to mimetically represent the human form, as abstraction and conceptual art kind of rise. And so at this time, we see anatomy and anatomical language being used by artists as more of a kind of conceptual conceit and a language of symbolism and an opportunity to explore themes of embodiment and the self and identity.

There’re several examples across the exhibition of artists using anatomical language not as a biological inquiry or a scientific exploration of the body, but more as a symbolic one. And I’ll pass this over to Naoko.

Takahatake: In February of 1967, Robert Rauschenberg came to Los Angeles to work on his first collaboration with Gemini G.E.L, the recently-founded artist workshop and publisher of limited edition prints and sculpture. Sidney Felsen, who’s one of the cofounders of Gemini, recalls picking up Rauschenberg at LAX and asking him if he had an idea for his project. To which the artist replied, “I’m thinking of doing a self-portrait of inner man.”

The following day, Rauschenberg asked Felsen to take him to a radiologist. He wanted to have a single-film x-ray of his entire body, head to foot. The only machine that had that capacity at the time in the United States was at the Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, and so the artist resorted to having his body x-rayed in six one-foot panels, which he pieced together.

X-radiography in this work becomes both a tool and subject for the artist. And that’s what you see here, dominating the center of the composition of Booster. This is Rauschenberg’s skeleton. He’s standing. It is his inner man, as it were. And surrounding him are familiar Rauschenberg motifs, such as the chair, the bodies of athletes, the directional arrows that indicate the rotation of the power drills.

Rauschenberg stood some five feet, ten inches tall. And so his composite skeleton exceeded the size of the available lithographic stones, and so the Gemini printers printed this from two separate stones, in two successive pulls, onto a single sheet of paper.

And so this recalls, for example, the work, the life-size figures of Cattani, which were composed from multiple plates. Both artists are adapting to the available printing and printmaking tools and materials. At the time Booster was printed, it was the largest hand-pulled lithograph ever made. I should conclude by noting that Booster discloses Rauschenberg’s keen interest in space exploration, and evidenced foremost in the title of the print, Booster. And in 1969, Rauschenberg would be invited by NASA to Cape Canaveral, to witness the launch of the Apollo 11 mission.

Cuno: And Thisbe, what about this object over here?

Gensler: There’s a really wonderful curatorial coincidence in this end of the gallery here that brings us to our final, and I think most stunning piece in the exhibition, which is Tavares Strachan’s sculpture, Robert, from 2018. And Tavares Strachan was the artist in residence at the Getty Research Institute from 2019 to 2020, I believe, and produced this glass and neon sculpture, which is a portrait of Robert Henry Lawrence, Jr., who was the first African American selected to be an astronaut by a national space program. And he tragically died in 1967, the year that Rauschenberg made his print Booster, interestingly. He tragically died in a training accident, in which he was instantly killed, and never made his way to space. And so he was also not recognized by NASA as an astronaut, for this reason, until 1997, thirty years later. And Tavares is interested in this historical figure mostly because he was left out of the historical narrative for so long

So what we’re looking at here is a pulsing neon figure that is part circulatory system, part skeleton. It is a floating body in a dark room. This body is floating weightless in space, with pulsing, flickering neon lights. And while this is a portrait of a historical figure, it is not a true likeness. There is no countenance that we can recognize, and we don’t see his skin color. We just see his interior anatomy. And this is— this use of the language of anatomy is part of an effort to speak to a universal humanity; that underneath our skin, we all have the same blood rushing through our veins, and we are all of one shared humanity.

Cuno: Well, this is a fascinating exhibition. Monique, Naoko, Thisbe, congratulations, and thank you for sharing it with us on this podcast episode.

Kornell: Thank you.

Takahatake: Thank you, Jim.

Gensler: Thanks so much.

Cuno: Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy is on view at the Getty Research Institute through July 10, 2022.

This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman, with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Myke Dodge Weiskopf. Our theme music comes from the “The Dharma at Big Sur” composed by John Adams, for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003, and is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday, subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts and if you have a question, or an idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu. Thanks for listening.

Jim Cuno: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

Monique Kornell: Berengario’s books show animated cadavers and skeletons set in a landscape, often...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

![Abdominal dissection; below: gall bladder and bile duct, after Jan Steven van Calcar, woodcut. From Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Basel: J. Oporinus, 1543), bk. 5, p. 365 [465], figs. 12, 13. Getty Research Institute, 84-B27611 Book page featuring partial torso and highlighting gall bladder and bile duct. There is text above and below the torso.](https://d3vjn2zm46gms2.cloudfront.net/blogs/2022/04/26105134/gri_84-B27611_ANT039_386633ds_2000x2000.jpg)

![Dissected woman, Jacques Fabien Gautier Dagoty. Color mezzotint. From Anatomie Générale des viscères en situation, de grandeur et couleur naturelle, avec l'angeologie, et la neurologie de chaque partie du corps humain (Paris: n.p., [1752]), pls. 1–3. San Marino, California, The Huntington Library, Los Angeles County Medical Association Collection of Prints and Ephemera, pri LACMA Color image of a woman, seen from the front. Her skin appears to be peeled back over one arm and below the breast to reveal her organs, muscles, and blood vessels.](https://d3vjn2zm46gms2.cloudfront.net/blogs/2022/04/26105159/gri_loa_ANT051OL_386640ds_800x800.jpg)

Comments on this post are now closed.