The Tomb of Nefertari project archive is a record of the conservation of one of the most important surviving examples of pharaonic art and a view into how the Getty Conservation Institute came to develop its blueprint for international, collaborative work. Here, the authors offer insights into the organizing of the archival record of this work, the process, and the contents of the archive. —Ed.

In 1986, only a year after its founding, the Getty Conservation Institute embarked on a major challenge: its first international collaborative field project, the conservation of the wall paintings in the 3,200-year-old tomb of Queen Nefertari in Egypt’s Valley of the Queens, undertaken in partnership with the Egyptian Antiquities Organization (EAO).

The tomb’s wall paintings, among the most important surviving examples of pharaonic art, depict Nefertari making offerings to the gods as she journeys toward the afterlife. Painted on layers of plaster to smooth the fractured limestone walls of the tomb, the images have had condition problems since their inception. Over three millennia, humidity fluctuations within the tomb caused salt from the limestone and plaster to crystalize, which in turn caused entire sheets of plaster to detach from the wall and paint to erode from the plastered surfaces. The damage, already evident when the tomb was opened in 1904 by Italian archaeologist Ernesto Schiaperelli, only accelerated in the years that followed through neglect and vandalism.

By the mid-1980s, nearly a quarter of the tomb’s paintings had been lost. To prevent further deterioration and treat existing damage, the Conservation Institute and Egyptian Antiquities Organization assembled a multidisciplinary international group of experts to undertake an intensive, multiyear, multiphase project.

Nefertari seated within a shrine, playing the game senet. Photo: Guillermo Aldana

The success of the Nefertari project helped establish a roadmap for the Conservation Institute’s future field work—work characterized by international collaboration, education and training, policy, advocacy, scholarship, and treatments informed by scientific research.

In late 2017, we completed archival processing of the project’s documentation, allowing these records to be made available to researchers and conservators for the first time. This archival work was a partnership between the Conservation Institute and the Getty’s Institutional Archives department, which collects and preserves records of enduring value that document the Getty’s work.

Log book from the conservation of the tomb of Nefertari. Institutional Records and Archives.The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

Preserving Project Records

Early on, the Conservation Institute recognized the importance of preserving its project records. Not long after work on Nefertari’s tomb ended, the Institute brought together files from staff who had participated in the project. By the time I (Lorain) was asked to help process the collection, files were spread out in 78 archival boxes and three flat file drawers. As I went through the boxes, I quickly realized the collection was much smaller than it appeared. I consolidated partially filled boxes and removed a great deal of material that was unnecessary to preserve. Several boxes, for example, contained drafts and galleys for publications, as well as reference materials easily found through online databases. There was also a copious amount of duplicate materials—not surprising since there was no central record keeper during the project, and project team members had many of the same memos and reports.

A few of the boxes showed early attempts to organize files into broad categories such as project administration, project findings, and reports. It was clear to me this file structure took away one’s understanding of how the project was carried out. The Nefertari project was important not only because it conserved a significant Egyptian treasure, but also in terms of how the project was structured. Unlike most conservation projects at the time, conservation treatment was not the beginning and the end of the project. The Conservation Institute took a comprehensive approach in its first field project by incorporating pre-treatment research, post-treatment monitoring, and site management planning. Because of the Institute’s pioneering approach to site conservation, I organized files by the different phases of the project to enable researchers to better understand how the project was carried out and the context in which the documents were created.

Electron micrographs (photos taken through a microscope) found in the archive demonstrate analysis carried out on plaster samples in the tomb. The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

Scientific Research

Data, reports, and photographs from the scientific analysis form a significant portion of the records, reflecting the integral role scientific research played in the project. Work on Nefertari’s tomb included analyses of the geologic, hydrologic, climatologic, microbal, and microfloral status of the tomb as well as chemical, spectrographic, and X-ray diffraction tests on plasters, pigments, and salts.

To treat the wall paintings, it was important to first understand the nature of the plaster upon which they were painted. The electron micrographs (photos taken through a microscope) found in the archive demonstrate analysis work carried out on plaster samples in the tomb.

While ancient Egyptians used clay-straw and gypsum plaster for wall paintings, the exact composition of the plaster varies from tomb to tomb. Even within Nefertari’s tomb, the number of plaster layers and the quality of the plaster vary throughout. Micrographs of samples from a single layer of ceiling plaster show that particles in the filler material have sharp edges, like that of crushed rock, which was readily available during construction of the tomb. Crushed rock produces a coarser form of plaster, whereas Nile sand, with its smooth and round particles, forms a finer layer of plaster that can be found elsewhere in the tomb.

Scientific analysis was also used to measure the effects of conservation treatment. In a hardbound log book, Conservation Institute scientist Michael Schilling meticulously documented color measurements of the wall paintings taken before and after cleaning to identify any color shifts that occurred.

Conservation log book with Polaroid photos of Conservation Institute scientist Michael Schilling at work in the tomb, his equipment, and his added notations. The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

Schilling taped data printouts, the size of small cash register receipts, into pages of the book, adding his handwritten notes to document his color measurement and calibration procedures. He also taped Polaroids of sections of the wall paintings where color measurements were taken, adding notations to the photos with a fine black marker. He concluded that the colors increased in saturation after cleaning, with no measurable change in hues.

Conservation

Renowned conservators Paolo and Laura Mora led the conservation team, with conservator Eduardo Porta serving as field coordinator for the project. The Moras, who came to the project with over 40 years of experience conserving wall paintings, developed a systematic approach for dealing with the wall paintings. Their approach was to: 1) conduct a complete survey of the wall paintings, 2) temporarily stabilize sections in the most precarious condition while the final treatment procedure was still under development, and 3) carry out final treatment of the paintings using reversible techniques with minimal intervention.

Paola and Laura Mora, Eduardo Porta, and other members of the conservation team working in the tomb. The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

Condition survey tables produced during the first phase illustrate the comprehensiveness that characterize the Moras’ work. These in-depth visual assessments of the wall paintings involved careful examination of the conditions of the support and paint layer, the results of previous conservation interventions, and the presence of salt crystallization.

Condition survey tables. The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

Photos of each section of the tomb were superimposed using four transparent acetate sheets with symbols identifying each type of deterioration and its location. The wall painting designs were then replicated in linear form along with the symbols. These linear drawings served as working copies for the conservation team.

Conservation treatment is detailed in progress reports by the Moras and in reports by graduate interns from the Courtauld Institute’s Conservation of Wall Painting program. In addition, five log books containing color photographs and handwritten entries by the Moras, Porta, and other members of the conservation team provide insight into daily conservation activities.

Log books containing color photographs and handwritten entries by the conservation team provide insight into daily conservation activities. The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

Entries are in English, Italian, and Arabic, reflecting the international makeup of the team. The entries typically list the location of treatment, the type of treatment, the treatment procedure, and the composition of solvents used. Some of the work involved removing unsystematic conservation treatments from the past. Describing his work on the west wall of the stairway, one conservator writes, “Cleaning by brush with acetone: water (50:50), and thinner. Consolidation with Paraloid B-72, 5%, & thinner. Removal of old repair, and application of new mortar.”

Entries are in English, Italian, and Arabic, reflecting the international makeup of the team. Stains from deteriorating adhesives are visible on the page. The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

Photos of sections of wall paintings as well as of the conservation team at work are taped to pages throughout the books, which, ironically, have turned the log books into a lesson in conservation themselves. Demonstrating the ravages of deteriorating adhesives, double-sided tape used to adhere the photos have stained the pages, bleeding through to the other side. In one log book, the adhesives have deteriorated to such an extent that photos have fallen off.

Site Protection and Planning

Although not initially part of the project, site protection planning was added when the Egyptian Antiquities Authority began discussing the possibility of reopening the tomb to visitors once conservation was completed.

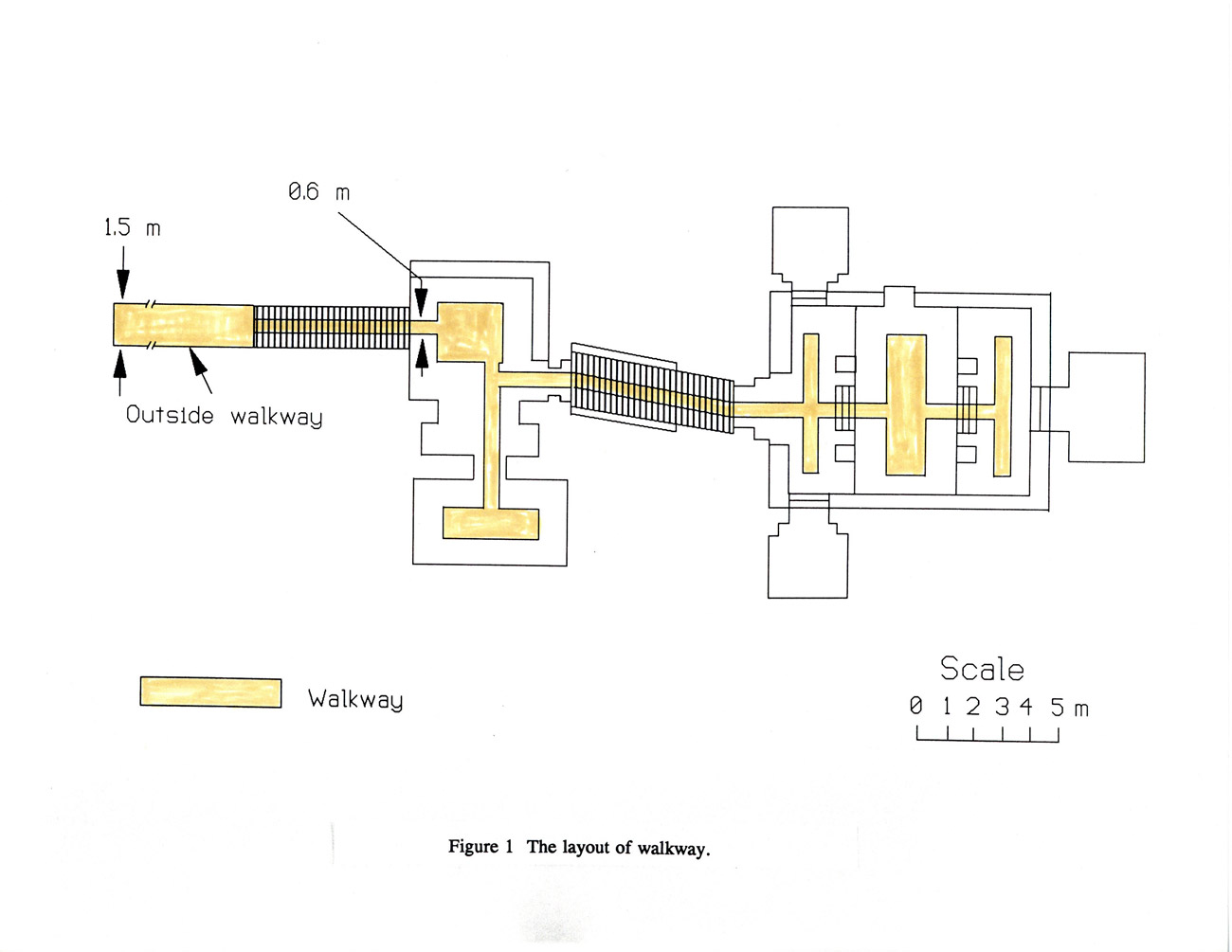

A walkway was installed to protect the floor, to control the spread of dust, and to keep visitors from touching the wall paintings. A diagram of the walkway and memos discussing its installation can be found in the records. The Getty Research Institute, Institutional Records and Archives, IA30008

A draft site protection plan written by the Conservation Institute lays out suggestions, a few of which were implemented, for the long-term protection of the tomb.

To measure the impact of visitors, an environmental monitoring station was installed, recording changes in air temperature, relative humidity, and carbon dioxide level. Environmental monitoring reports in the collection include charts of these changes over the course of the year, showing that while the temperature remained steady inside the tomb, the relative humidity fluctuated widely with seasonal changes, human presence, and the use of a specially installed ventilation fan during conservation treatment. A walkway was also installed to protect the floor and control the spread of dust, and most importantly, to keep visitors from touching the wall paintings. A diagram of the walkway and memos discussing its installation can be found in the records.

Educating the Profession and the Public

Art and Eternity: The Nefertari Wall Paintings Conservation Project, 1986-1992, edited by Miguel Angel Corzo and Mahasti Ziai Afshar, serves as the final project report.

Disseminating project results was an important part of the project, and the records show that the Conservation Institute went to great lengths to educate the public about the tomb of Nefertari and the conservation of its wall paintings.

Researchers will find records related to the three publications produced from the project: Wall Paintings of the Tomb of Nefertari: First Progress Report (1987), the final project report Art and Eternity: The Nefertari Wall Painting Conservation Project 1986–1992 (1993), and the image-rich publication House of Eternity: The Tomb of Nefertari (1996). There are also files pertaining to Nefertari: For Whom the Sun Shines (1997), a film production of the Getty Conservation Institute, the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, and the BBC, as well as Nefertari: The Search for Eternal Life (1993), a video co-produced by the Conservation Institute and Televisa.

In addition, the Conservation Institute helped organize two exhibitions. In the Tomb of Nefertari: Conservation of the Wall Paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum (November 1992–February 1993) included a life-size, post-conservation photographic replica of one of the tomb’s chambers. The Institute also collaborated with the Fondazione Memmo to organize Nefertari: Light of Egypt (Nefertari, luce d’Egitto), at the Palazzo Ruspoli in Rome (October 1994–February 1995), which featured a virtual reality display of the tomb. The exhibition traveled to Promotrice delle Belle Arti, in Turin (December 1995-April 1996) and to Bari, Italy (Spring 1997).

For Researchers: Accessing the Archive

For researchers interested in various aspects of the conservation of the tomb’s wall paintings, the Nefertari project records provide in-depth documentation of the project and insight into the inner workings of the collaboration between the Conservation Institute and Egyptian Antiquities Organization. The tomb of Nefertari project records are available to qualified researchers for on-site use at the Getty Research Institute. Learn more about using the Getty library here.

Excellent article. Wish I could be there and see for myself. Thank you for letting us all be on site.

I followed your earlier efforts and have been in the tomb. I struggled with this article however. Egyptology has invented all these epithets, like material record, but most writers and speakers fail to define them. So I kept guessing. Is it about the material of the original tomb construction, the materials of the repairs, the materials of the paper records kept of the real work with the materials to fix the tomb paintings, or maybe even the materials of the offerings offered or to the Queen. I suppose I shall survive this phase of Egyptology, where materiality can also mean how high was your wooden coffin.

Hi

My name is Jordi Puig and I’m a professor in UB (University of Barcelona). Nowadays I’m researching about Nefertari’s Tomb and I read your project, but I need More information. Could bé possible to have More information about the Nefertari’s rectoration Project (Photos, maps, notes) ? It could be very interesting for my students.

Thank you in advance

Jordi Puig Voltas