During World War II the Nazis stole unimaginable amounts of artwork. Paintings, sculptures, books, furniture, and jewels were taken by the Nazis for their personal collections, sold at forced auctions, or stored in castles, bunkers, mines, and other secure locations.

Several objects once owned by the Lederers, a prominent Jewish family, were part of this story.

Serena Pulitzer Lederer, 1889, Gustav Klimt. Oil on canvas, 75 1/8 x 33 5/8 in. Purchase, Wolfe Fund, and Rogers and Munsey Funds, Gift of Henry Walters, and Bequests of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe and Collis P. Huntington, by exchange, 1980. Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org

August and Serena Lederer

A Jewish family living in high-society Austria, the Lederers had an extensive art collection and were great patrons of Gustav Klimt. August and Serena Lederer owned a number of his paintings, including portraits of Serena, her mother, and her daughter. Between 1938 and 1939, the Lederer collection was subject to Aryanization, a euphemism for the Nazis’ confiscation of Jewish-owned property, including businesses, homes, household goods, and artwork. The greatest of these artworks were destined for Hitler’s never-realized museum in Linz, Austria.

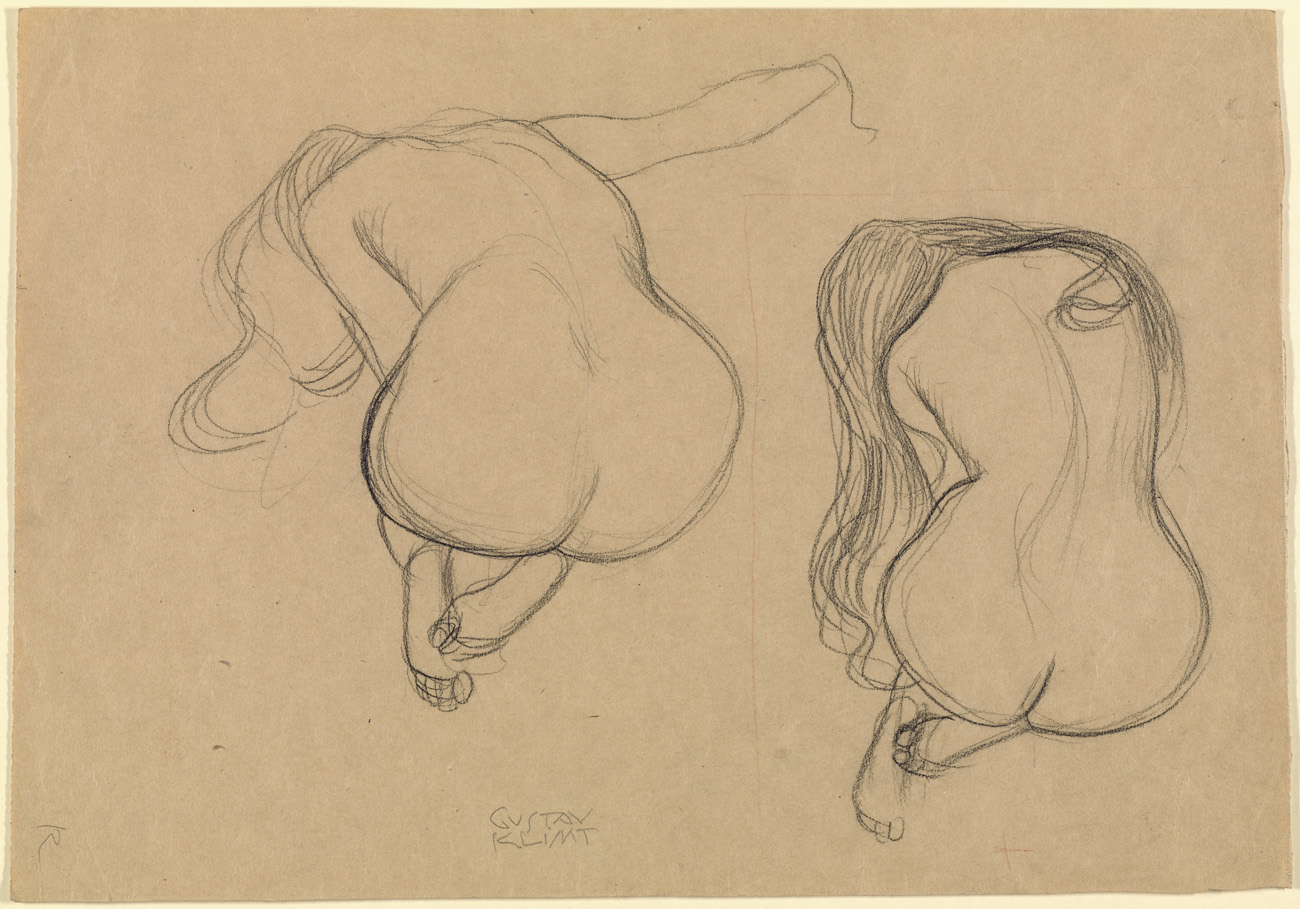

Two Studies of a Seated Nude with Long Hair, about 1901–02, Gustav Klimt. Black chalk and red pencil, 12 1/2 x 17 13/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009.57.2. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The Gestapo seized most of the Lederers’ art, including works that now reside in the Getty Museum’s permanent collection: a 14th-century panel painting, a 15th-century Italian glazed jar, and the 16th-century elephant shown at the top of this post. So how did these works go from the walls of a Viennese home to the halls of the Getty Museum?

Following the Provenance Bread Crumbs

Let’s follow the provenance—history of locations and ownership—for three of these works to figure out what happened. The story can be retraced using the Museum’s online collection, which contains extensive provenance data.

The elephant and the relief-blue jar were seized on November 26, 1938, from the home of the newly widowed Serena Lederer (August had died in 1936). A year later, the Gestapo stripped the Lederer family residence of valuables, taking the St. Luke panel painting with them. Serena fled to Budapest in 1940, dying there three years later.

St. Luke, 1330s, Simone Martini. Tempera and gold leaf on panel, 26 9/16 x 19 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 82.PB.72. Relief-Blue Jar with Harpies and Birds, about 1420–40, probably the workshop of Piero di Mazzeo. Tin-glazed earthenware, 12 1/4 × 5 5/8 × 11 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.DE.56. Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

All three works were first stored at a depot in Neue Burg, Vienna. On March 30, 1942, the panel painting and the Italian jar were moved to the Reichsbank (the German National Bank). By October 7, 1943, they moved yet again to the salt mines in Altaussee, Austria, the Nazis’ largest storage site for looted artworks, most of which were intended for Hitler’s Linz Museum. The elephant, however, stayed in Neue Berg until January 29, 1944, when it was moved to Thurntal Palace in Lower Austria.

By May 8, 1945, the Allied forces had taken control of the palace and many other sites used by the Nazis to store art, at which point the long, complicated process of returning the artworks to their rightful owners began. The Nazis regularly recorded most objects they confiscated, including where it came from and where it was stored, which allowed many pieces to be returned to their proper owners—when they could be found—or to government agencies. Nonetheless, restitution research and claims continue to this day.

Altaussee, Austria, May 1945: One of the many mine chambers in which the Nazis constructed wooden shelves to house stolen works of art. To understand the volume of space in this one chamber, note the nine-foot ladder at center right. Photo: Robert Posey Collection, courtesy of the Monuments Men Foundation. All rights reserved

From Geneva to L.A.

Thousands of artworks were lost or destroyed during the war. The Lederers lost a number of Gustav Klimt paintings, which were burned by retreating German SS forces to stop them from falling into enemy hands. However, other works from their collection survived, and by 1948 most of them had been returned to Erich Lederer, the son of August and Serena, who had moved to Geneva. They remained in his possession until his death in 1985.

In this same year, his widow then decided to sell the collection, and masterpieces from the Lederer collection are now found in several major museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The elephant, panel, and jar, along with a group of paintings and small-scale bronzes, were sold to the Getty Museum, where they have been admired by visitors for over 30 years.

Bronzes now in the Getty Museum collection. Top row, left to right: Putto Holding Shield to His Right, about 1650–55, Ferdinando Tacca; Kicking Horse, about 1630, Caspar Gras; Group of Eleven Figures (Allegory of Autumn), about 1725, Francesco Bertos. Bottom row, left to right: Satyr, 1543–45, Benvenuto Cellini; Putto Holding Shield to His Left, 1650–55, Ferdinando Tacca; Bull with Lowered Head, about 1510–25, Italian. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.SB.70.2, 85.SB.72, 85.SB.74 (top row); 85.SB.69, 85.SB.70.1, 85.SB.65 (bottom row). Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

More about Provenance

Interested in learning more about wartime provenance? Browse the Getty Research Institute’s list of research resources for Holocaust-era looted art and its vast database of digitized German art-sales records from the 1930s, part of the freely searchable Getty Provenance Index®. For more provenance stories, follow the monthly #ProvenancePeek series, which spotlights artwork histories from the Getty archives.

Further Reading

- Alford, Kenneth D. Hermann Goring and the Nazi Art Collection: The Looting of Europe’s Art Treasures and Their Dispersal After World War II. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012.

- Bisori, Maria and Emmanouil Galanakis. “Doctors Versus Artists: Gustav Klimt’s ‘Medicine.’” BMJ: British Medical Journal 325, no. 7378 (2002): 1506–1508.

- Pope-Hennessy, John, Katherine Baetjer, Charles S. Moffett, Walter A. Liedtke, and Lucy Oakley. “European Paintings.” Notable Acquisitions (Metropolitan Museum of Art), no. 1980/1981: 43–47.

- Vergo, Peter. “Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze.” The Burlington Magazine, 115, no. 839 (1973): 108–113.

I enjoyed reading “The Lederer Collection: Lost and Found.” It seems to me that the Lederer Klimt Collection has not gotten the attention it deserves.