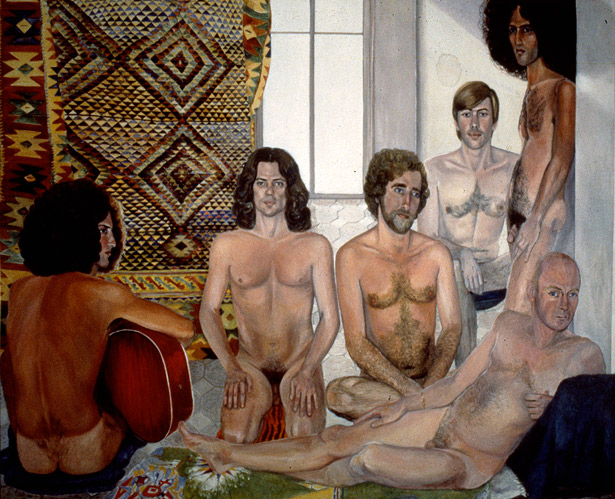

The Turkish Bath, Sylvia Sleigh, 1973. Scan of slide from the Sylvia Sleigh papers. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4. Gift of Sylvia Sleigh and The Estate of Sylvia Sleigh Alloway. Artwork © Estate of Sylvia Sleigh. Here Sleigh uses Ingres’ painting of the same name as a vehicle to portray five men she respected and cared for: art critics Lawrence Alloway, Scott Burton, John Perreault, and Carter Ratcliff with two images of her frequent model Paul Rosano.

Much of the work of the contemporary figurative realist painter Sylvia Sleigh, whose papers are now open to researchers at the Getty Research Institute, is by no means boring; nudity always has a way of catching one’s eye. However, what may first appear brazen is actually quite quotidian in nature: sex, love, friendship—intimate relationships visualized. The figures depicted throughout Sleigh’s work are, without fail, people she knew and cared for greatly. Their nudity is, among other things, a representation of our vulnerability in relationships—the way in which we bare our souls and ask for acceptance is comparable to exposing our bodies.

This theme translates easily to the archival world, where a certain measure of voyeurism and vulnerability is always present. Unmediated access to an artist’s papers—which often include correspondence and journals—can be a true glimpse into another’s life. Who are the personalities behind art history? What did they think about? Who did they see? Heck, what did they buy at the grocery store? The answers are all there, in acid-free boxes, waiting to be discovered.

In the case of Sleigh’s papers, we at the GRI are fortunate to have two sides of the story, as our holdings also include a companion collection, the papers of her husband, noted art critic Lawrence Alloway. And herein lies additional context for what one may find in Sleigh’s papers, and in Alloway’s. The relationships we have with the people closest to us, those with which we allow ourselves to be most vulnerable, seep into other areas of our lives. Through the two collections, we can view the works of Sleigh and Alloway, and indeed their lives, from privileged perspectives. We can see how their intimate relationship inspired and manifested in their work—both formally and informally.

At the Café, Sylvia Sleigh, 1951. Scan of slide from the Sylvia Sleigh papers. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4. Gift of Sylvia Sleigh and The Estate of Sylvia Sleigh Alloway. Artwork © Estate of Sylvia Sleigh. Sleigh writes that this painting “commemorates the many times that I had to leave Lawrence and return to Pett. … I hated leaving Lawrence. Many times when he took me to the station we went to a café while waiting for my train.”

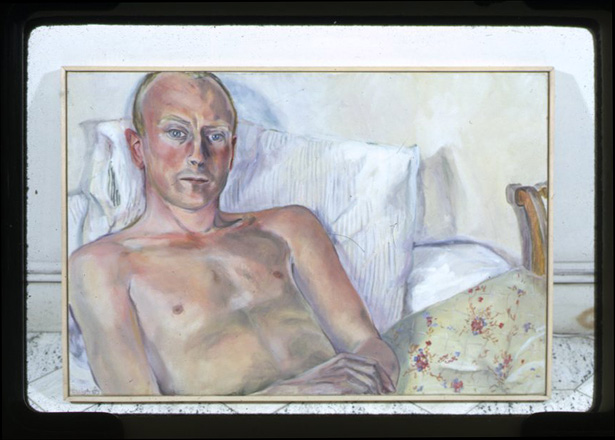

Lawrence in Bed (Ditchling), Sylvia Sleigh, 1959. Slide from the Sylvia Sleigh papers. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4. Gift of Sylvia Sleigh and The Estate of Sylvia Sleigh Alloway. Artwork © Estate of Sylvia Sleigh

Alloway appears in over 60 of Sleigh’s works over a 40-plus year time span. In turn, Sleigh’s feminist activism no doubt encouraged Alloway’s championing of women artists and pro-feminist writings.

Art ABC, Lawrence Alloway, 1968. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4. Gift of Sylvia Sleigh and The Estate of Sylvia Sleigh Alloway. Top row, left to right: Notepad cover, title page, A is for Attributed to Hubert Robert, D is for Batman does Duchamp. Bottom row, left to right: P is for Psychedelic Artist, X is for Kisses, and alphabet key

Less well known than his published works are the tiny gifts Alloway created for Sleigh, which exemplify his predilection for pop art and through which he expressed his love. Many of the small-sized notepads contain clippings from comic books that Alloway devised into “alphabets,” where each picture represents a word and corresponds to a letter.

Perhaps the most uncommon and prolific aspect of both Sleigh and Alloway’s papers is the correspondence written by and to each other. When Sleigh and Alloway first met in an art history class in London, Sleigh was 27 and married to Michael Greenwood, and Alloway was 17. For the next ten years their relationship grew and deepened, eventually becoming romantic. Daily letters between Sleigh and Alloway chronicle their passionate relationship for years, until 1954 when Sleigh divorced Greenwood and, within a matter of months, married Alloway.

Completing the story are letters exchanged concurrently between Sleigh and Greenwood. Sleigh and Alloway wrote of such affection and torment—the letters are enthralling. Alloway writes in a letter of October 23, 1949, “I assure you if I don’t see you soon I shall sweep you off as Hades did Persephone. I adore you and am longing to see you.[…]I love you so much. You must not put off your day of arrival, no matter how reasonable the objections are that [Michael] raise. Hurry.”

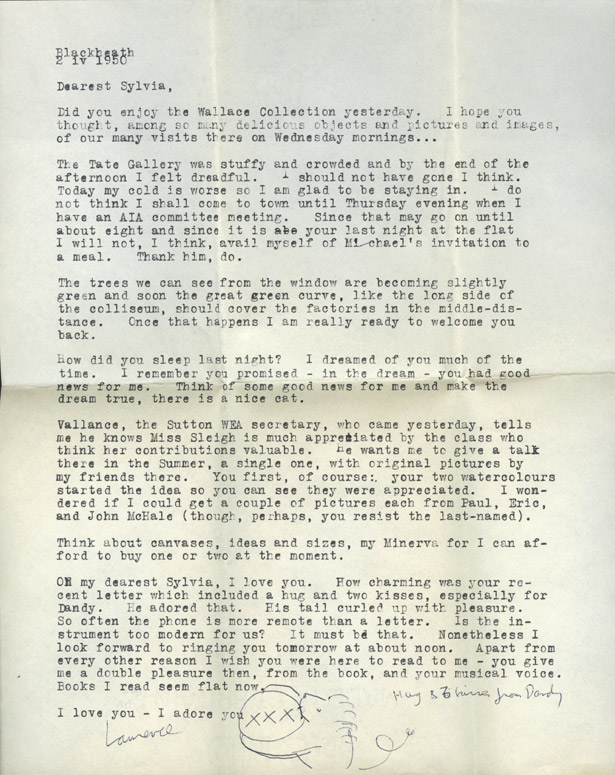

Alloway frequently portrayed himself as other characters in his letters, most often as “Dandy,” his lion alter ego. It’s as if he loved Sleigh more than one person could and created more characters to contain all that he felt. In the below letter, Alloway writes how Dandy’s “tail curled up with pleasure” at one of Sleigh’s recent letters. Like any good bibliophile, I’m particularly fond of the line, “apart from every other reason I wish you were here to read to me—you give me a double pleasure then, from the book, and your musical voice. Books I read seem flat now.”

Letter from Lawrence Alloway to Sylvia Sleigh, April 2, 1950. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4. Gift of Sylvia Sleigh and The Estate of Sylvia Sleigh Alloway

And in the November 9, 1949, letter shown below, he closes befittingly, “I love you, madly, intellectually, impulsively, constantly, I love love love you.”

Letter from Lawrence Alloway to Sylvia Sleigh, November 9, 1949. Alloway writes to Sleigh on the eve of his visit to Sleigh’s exhibition at the Kensington Gallery. He describes his excitement with words and drawings, portraying himself as “Dandy,” his lion alter ego. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.M.4. Gift of Sylvia Sleigh and The Estate of Sylvia Sleigh Alloway

See all posts in this series »

What a treasure!….for the Getty’s and the world! Thanks for sharing this taste.