Eileen Cowin in her studio, 2011

In the exhibition Narrative Interventions in Photography, opening October 25, contemporary photographers Eileen Cowin, Carrie Mae Weems, and Simryn Gill present works that explore the subjectivity of storytelling and the slipperiness of truth.

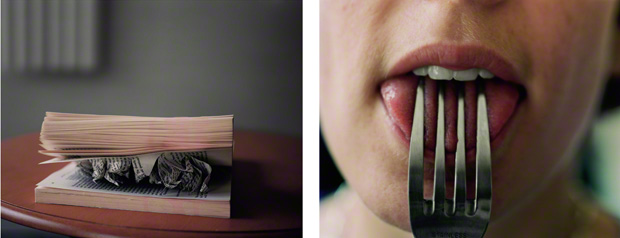

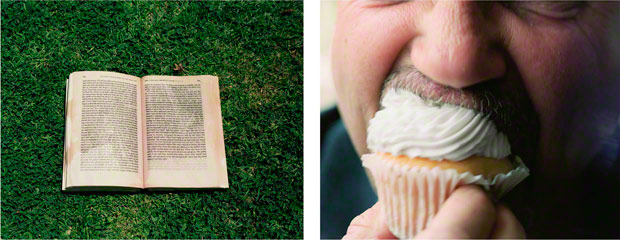

Cowin’s large, color photographs pair images—including one of a woman pressing a fork against her tongue with one of a mutilated book—which suggest that words in all forms can deceive. Cowin talked with me at her Los Angeles studio about I See What You’re Saying, her series of photographs in the exhibition, as well as her love of film and books, both fiction and non-fiction.

I See What You’re Saying, Eileen Cowin, negatives, 2002; prints, 2005. Inkjet prints, each image 36 x 46 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010.53. © Eileen Cowin

You said a radio program inspired you to create I See What You’re Saying?

I’m so interested in lying in every possible way, on a personal level and on a political level. I had just heard a piece on National Public Radio about lying, and there was a teacher at Mount Holyoke College who was lying to his students. He said he served in Vietnam and lied about being on the football team and catching the winning pass. I can’t believe the things people think they can get away with. I deal with this in my video Pants on Fire.

Video courtesy of Eileen Cowin. © Eileen Cowin

Do you think people sometimes don’t even know they are being untruthful?

People somehow don’t start off thinking that they are going to lie. They just get caught up and they can’t separate fact from fiction and soon they believe it themselves.

Doesn’t the fact that memories fade make it hard to determine if someone is being intentionally deceitful?

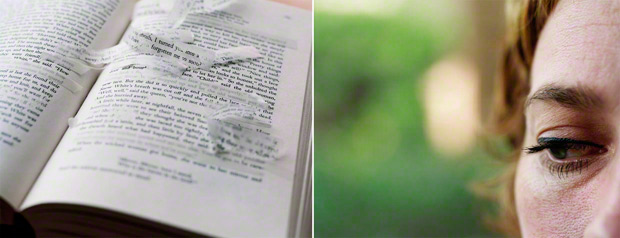

Right. Lying is so ambiguous because you may remember something, and someone else might remember it in a different way. I love the idea of people telling a story from different points of view. One of my key movies of all time is Rashomon. Is it about lying or memory or a reliable witness? Who is telling the truth? They all are.

I See What You’re Saying, Eileen Cowin, negatives, 2002; prints, 2011. Inkjet prints, each image 36 x 46 in. Image courtesy of the artist. © Eileen Cowin

What are you reading now?

I read a lot of fiction. Right now, I am looking at books about the events of 9/11 to see how writers like Don DeLillo and Helen Schulman were able to deal with these events that are so heartbreaking. I am in awe of people who can write amazing books.

Besides being a voracious reader, you also use books as props in your photographs.

Some of the books I’ve used in the piece I See What You’re Saying are about fairy tales, because I’d just done a video on the relationships of fairy tales to family history. It was called “…and the daughter married the prince.” People wish life was a fairy tale, but fairy tales can be horrific.

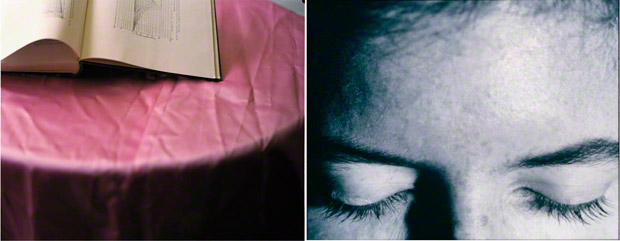

I See What You’re Saying, Eileen Cowin, negatives, 2002; prints, 2011. Inkjet prints, each image 36 x 46 in. Image courtesy of the artist. © Eileen Cowin

You talk about not wanting to appear “hokey” in your work. What do you mean?

I’m not trying to solve a problem in my work. It’s not, “here’s an equation and here’s the answer.” I don’t want to be hokey, corny, or melodramatic. I heard Tom Robbins lecture a long time ago at UCLA. He said there’s a line—and you want to get right on that line. If you don’t get close enough, there’s a disconnect. If you go over, it’s exaggerated and silly and obvious.

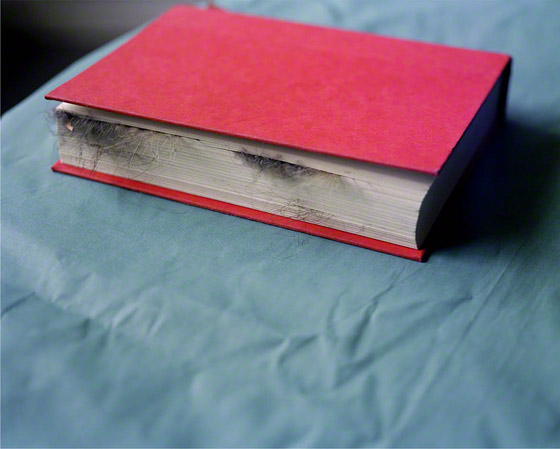

Your work is very, um, hairy. In I See What You’re Saying, a book is sprouting hair and a mustachioed man is eating a cupcake.

Victorians used to make sculpture out of hair and braided flowers. You look at it and you’re repelled, but also fascinated. I wasn’t interested in the beauty of the hair. It’s about a history coming from the book.

I See What You’re Saying, Eileen Cowin, negative, 2002; print, 2011. Inkjet print, 36 x 46 in. Image courtesy of the artist. © Eileen Cowin

I See What You’re Saying, Eileen Cowin, negatives, 2002; prints, 2011. Inkjet prints, each image 36 x 46 in. Image courtesy of the artist. © Eileen Cowin

As a videographer, you’re also interested in storytelling in film?

You know when you go the movies and the ending is just tied up in a little package, and how disappointing that can be? On KPCC’s FilmWeek on Air Talk, a critic said he had no qualms giving away the whole story in his review; another critic said he didn’t want to do that because people say they don’t want that. I don’t want that. Sometimes I’ll read the first paragraph of a film review and that’s all. I don’t want to know the ending. I want things to be played out, unraveled. I like unraveling.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Very inspiring work, thank you !

Smashing work…mysterious and curious and long lasting in the emotional being considering relationships of all kinds. Draws one into dreamland; sometimes mildly disturbing!

Smart, sensuous, and ultimately troubling. You’ve always aimed your camera at situations of questioning, where human interactions assume qualities of the theatrical, even when the players don’t know they’re playing. The distressed books resonate for me (of course!), but to juxtapose what’s happened to those pages with eyes in motion away from the camera is to regard one reading as being read . . .