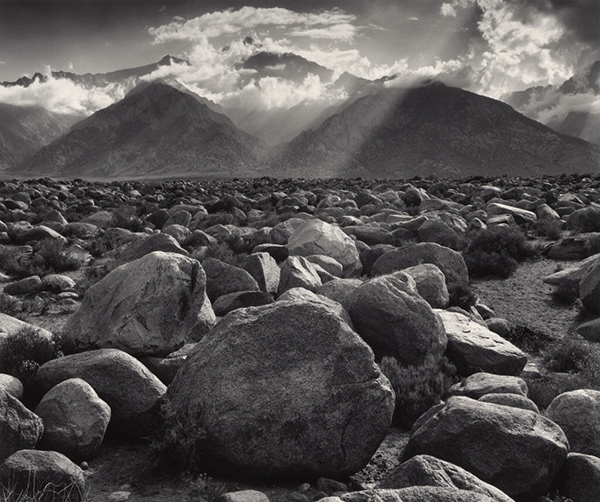

Mt. Williamson, Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California, negative 1944; print 1981, Ansel Adams. Gelatin silver print, 15 3/8 x 18 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.83.3. Gift of Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin in Memory of Marjorie and Leonard Vernon © 2014 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

At the time I applied for the job, I was a graduate student in the master of fine arts program at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Like my peers, I thought I’d make my way as a photographer by teaching.

But then one day I stumbled on an ad in Artweek for an editorial assistant opening at the Friends of Photography, a nonprofit organization that Ansel founded in 1967 to present exhibitions, publications and educational workshops in fine art photography. Jobs like that didn’t come around often. From my vantage point as a student, a paying job of any sort in the arts seemed a rarity, but one with a living legend was unimaginable.

But then one day I stumbled on an ad in Artweek for an editorial assistant opening at the Friends of Photography, a nonprofit organization that Ansel founded in 1967 to present exhibitions, publications and educational workshops in fine art photography. Jobs like that didn’t come around often. From my vantage point as a student, a paying job of any sort in the arts seemed a rarity, but one with a living legend was unimaginable.Figuring it was a long shot, I put a letter and resume in the mail. To my surprise, I was called to an interview—and I got the job. I packed my newly minted graduate degree and few possessions in a small U-Haul truck, hitched my old powder-blue VW wagon to the back, then descended from the Sandia Mountains, straight-lined it across Arizona and the Mojave, and arrived at the sleepy seaside town of Carmel, California.

Carmel was socked in fog, and cold. And this was in May. The sun didn’t really come out until October. I remember driving around the peninsula both day and night, headlights bouncing wildly through the fog, pine trees looming in and out of focus. Bundled in sweaters, I had arrived in a new and different world.

The world I’d left behind in New Mexico was as different aesthetically as it was in terms of terrain. My graduate program was recognized nationally as a lab for visual experimentation. We were about breaking rules, not observing them.

And yet here I was, working for the man who wrote the rulebook on photography. Ansel is famous for having invented the Zone System, a mechanical process for reading light and exposing and developing black-and-white photographs. He published several definitive volumes on photographic techniques—depth of field, the use of filters, and the chemistry of film processing.

It wasn’t where I expected to find myself. In fact, when Jim Alinder, the Friends’ charismatic director, asked me in the job interview what I thought about Ansel’s work, I hadn’t known what to say. I think I mumbled something that must have been passable, but only barely, I’m sure.

In Albuquerque we referred to Ansel and his peers, with some superiority, as the “rocks and roots” school of photography. Such hubris. As if we were capable of producing anything that could begin to match Ansel’s visual elegance and technical proficiency. Ha!

It brought me up short to meet Mr. Rocks and Roots himself. I was expecting someone formal and aloof. Ansel was anything but. He was big, warm, erudite, and funny. With his bola ties and crooked nose—a souvenir of a tumble he took as a small boy in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake—he was utterly unintimidating. Until he started to talk photography.

Ansel was equal parts artist and scientist. Visiting him in the darkroom after viewing his prints felt like meeting the wizard behind the curtain—except in this case, what was behind the curtain was a huge, state-of-the art-laboratory, in pristine order. The darkroom stood as a sleek counterpart to the rugged business of his hauling photographic equipment out into the landscape where, with infinite patience and a precise combination of lenses and filters, he captured his famous images.

The darkrooms I’d frequented as a graduate student were reasonably well equipped, but my approach to developing photographs had been a bit slapdash, happily accommodating accidents, and always looking for shortcuts. Ansel’s photographs were not just the result of his having caught a moment in time, but of his having interpreted and expressed that moment later, in subtle gradations of silver. Ansel used to say that the negative is the score, and the print is the performance. I could hum a tune. He was conducting an orchestra.

A collection of Ansel’s exquisitely meticulous photographs is on view now until July 20 at the Getty Center. In Focus: Ansel Adams includes prints that were originally purchased by Leonard and Marjorie Vernon, prominent collectors who played an important role in the stewardship of the Friends of Photography. Their daughter, Carol Vernon, and her husband, Robert Turbin, recently donated the set to the Getty.

The Vernons were kind, wonderful people who were fixtures in Carmel, even though their home was in Los Angeles. Leonard was a successful industrial developer who loaned his keen business expertise to the Friends’ board. Together, he and Marjorie also shared a passion for photography, and collecting.

The Museum Set on display at the Getty spans several decades of Ansel’s career; nearly all of the photographs were taken long before I worked at the Friends. They are drawn from some of the 70 photographs that Ansel selected as the best from among his thousands to be part of this collectors’ set. Production of the Museum Set began in the late 1970s, and was still underway when I was in Carmel in the early 1980s.

Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite Valley, California, negative 1960; print 1980, Ansel Adams. Gelatin silver print, 19 1/2 x 14 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.83.19. Gift of Carol Vernon and Robert Turbin in Memory of Marjorie and Leonard Vernon. © 2014 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

After a year or so, I was given the privilege of running the summer workshops with guest faculty that included amazing artists like Annie Leibovitz, Roy DeCarava, and Mary Ellen Mark. Ansel and his staff took participants on field trips to Point Lobos to photograph the rock pools, surf, and cypress trees. At day’s end, we adjourned to Ansel’s magnificent home in the Carmel Highlands. Martinis were served while we gazed at the Pacific, hoping for a glimpse of the “green flash” at sunset, one of Ansel’s favorite pastimes.

Ansel and his wife, Virginia, were gracious hosts who loved to open their home to guests. Their house was magnificent: high-ceilinged, with huge picture windows, and Virginia’s orchid collection silhouetted against the coastal view. There was a massive stone fireplace with an ancient Chinese drum mounted on the wall above it, and a grand piano, which Ansel—trained as a classical pianist before turning to photography—often played. Among his regular visitors were accomplished musicians—the most famous being piano virtuoso Vladimir Ashkenazy.

One of my favorite memories is of Ansel’s 80th birthday party in February 1982. There were three exhibitions of Ansel’s photographs on display that month in and around Carmel—at the Friends of Photography, the Weston Gallery, and the Monterey Museum of Art. On the night of the big bash, Ansel attended each opening, crossing the peninsula in his white Cadillac, with its “Zone V” vanity license plate. He was serenaded by an 80-piece marching band from Salinas High School and presented with the Medal of the French Legion of Honor. One hundred guests from all over the world flew in for a sit-down dinner. A chef presented an enormous cake that was supposed to represent Half Dome—except the chef had never actually seen Half Dome, so you might have mistaken it for Space Mountain, or maybe Vesuvius. Ansel loved it all.

Ansel Adams enjoying his 80th birthday cake modeled after Half Dome. Photo © Jim Alinder

All this will be on my mind when I gather with other museum visitors to gaze at the impossibly perfect images of “Moon and Half Dome,” or “Dogwood Blossoms in Yosemite National Park” at the Getty. I will think of Ansel’s articulate, statesmanly defense of our natural resources. I will think of his alchemy in the darkroom, teasing silver gelatin into an exquisite luminescence. I will think of him holding court in his living room, telling the story of how he captured the sun streaking over those boulders at Mt. Williamson, in Manzanar. And I will revel in the memory of being a young person in Ansel’s orbit during that heady time. We learned from Ansel the importance of looking closely, very closely, at the world. And, though few of us would get it right, that preserving the wonder and beauty around us is a worthy goal, and in its way, a sacred pursuit.

Comments on this post are now closed.