Students are often lectured at, asked to receive information and not question what is being said. As a college student, I’ve experienced this first-hand.

This summer, I got to explore more creative approaches to learning as part of the team planning the annual alumni event for teacher graduates of the Museum Education Department’s one-year professional development program, Art & Language Arts. This program introduces K-5 teachers to innovative approaches to fostering visual and language arts learning in the classroom. This year’s theme was “Creativity and Innovation,” and the goal was to help teachers generate and utilize out-of-the-box approaches to teaching art, learning from art, and making art.

The morning of the alumni event, held August 11, was packed with lectures and an activity from our keynote speakers, artist Mark Bradford and poet Douglas Kearney, who talked about their artistic practices and shared their thoughts on classroom learning. Bradford advocated for encouraging students to understand that art comes from all around us—it doesn’t necessarily need to be “on top of the hill.” In fact, he said, “everything [we] see is art.”

Following Bradford’s presentation, Kearney performed some of his own poetry and led an interactive multisensory poetry activity prompting teachers to write poetry inspired by artworks in the Getty Museum’s collection—and to get them to think of poetry as more than haiku.

The afternoon included four sessions with gallery activities and art-making workshops. I created an activity that invited participants to think about their identity and that fostered choice and play. In this two-part workshop, titled “Appropriate and Innovate: Decorative Arts for Contemporary Times,” we began by looking closely at the forms and functions of furniture pieces in the Rococo paneled room. Through close looking, we discovered who the owner might have been: a wealthy Parisian nobleman, possibly well-traveled and interested in showcasing his exotic displays of world cultures as signified by a commode, four-panel screen, pair of globes, and elephant figurine. And he probably kept his files top secret, as seen in the three different tables with locks and secret compartments. By taking the time to observe closely, curiosity led us to insightful ideas and conclusions.

Teachers look closely at the forms, functions, and design motifs of decorative art objects at the Art & Language Arts alumni event at the Getty Center on August 11, 2012.

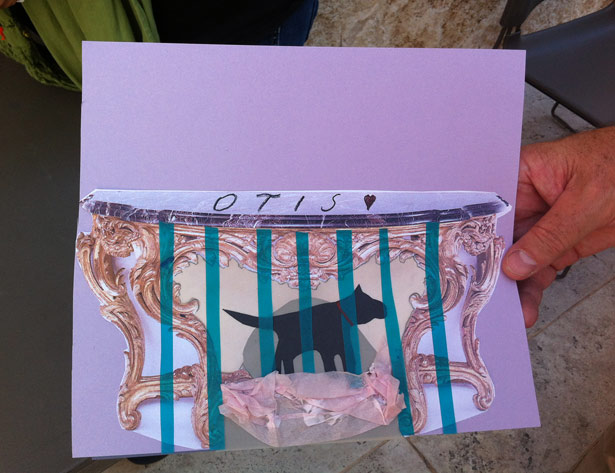

Based on our conversations in the gallery, I then asked teachers to pick a piece of furniture that struck them visually and to “appropriate” it into a contemporary object that reflected their identity. Using color copies of the furniture in the gallery, along with papers, markers, color pencils, glue, and scissors—all affordable and accessible materials for the classroom—they explored their chosen object’s existing form and function, and experimented with adding or subtracting elements to make it their own.

By the end of the session, teachers had not only explored the Museum’s collection and their own identity, but had also discovered an activity to introduce with their own students. Furniture is something most students have in their homes and classrooms—they can find connections between a Rococo writing table and their desks at school, for instance.

The activity uses simple materials but has complex goals. By taking 18th-century objects made for Parisian noblemen and appropriating them to fit students’ own tastes and identities, students make unique pieces connected to their lived experiences. They consider patterns and motifs, forms and functions that best represent their place in the world. And they open up a critical language that goes beyond “I like it;” they learn to communicate about themselves and their world (fictitious or real), and how different or similar their world may be to that of a Parisian nobleman. They take a wealth of sources from the world around them, reflect on them, and make art from them. As Mark Bradford said: “art is all around you.”

Collage inspired by an 18th-century table, and the love of a dog named Otis, created by a participant in the Art and Language Arts alumni event.

As an art student, developing this activity was also meaningful for my own practice and my connection with the Museum. My paintings and performances are rooted in my grandmother’s diasporic narratives across Asia. More and more, I find myself wanting to engage with cross-cultural and cross-generational communities in my native Los Angeles. Before my internship this summer, I had visited the Getty Center and the Getty Villa on multiple occasions, but felt very distant and excluded from the Getty’s primarily western European collection. I don’t remember being excited by a work of art except for Van Gogh’s Irises, and that was only because I self-identified with the title of the work.

Because of my internship, I enjoyed a space to reconsider my reactionary sentiments about the representation of upper-class western Europeans in art collections, and how I could address those sentiments creatively with people who may feel similarly. I was fortunate enough to work with an incredibly encouraging supervisor, Theresa Sotto in teacher programs, who was supportive of my ideas. The challenge for me this summer was to provide a space for visitors to identify with, contest, reject, or fantasize about the histories and identities of collection objects while making relevant connections to their lived experiences. Encouraging students to make personal connections with art collections is one way to ensure that museums continue to build relationships with the heterogeneous communities of Los Angeles 10 years from now, 50 years from now, 100 years from now.

Comments on this post are now closed.