The Villa Teen Apprentices will see you now. Front row, left to right: Danielle Bui, McKenzie Givens, Jenny Lee, Jackie Ibragimov. Back row, left to right: Alexandra Cogbill, Mattias Rosenberg, Sara Rygiel, Sebastian Hart, Gaby Chitwood, Kate Hinrichs. (Not pictured: Kailyn Flowers, Pilar Marin.)

Throughout 2013, the Getty community participated in a rotation-curation experiment using the Getty Iris, Twitter, and Facebook. Each week a new staff member took the helm of our social media to chat with you directly and share a passion for a specific topic—from museum education to Renaissance art to web development. Getty Voices concluded in February 2014.

White walls, gorgeous bodies, and lots of fine, fine, heavy wine seem to characterize the modern-day perception of the ancient world. For generations, the picturesque marble ruins of Athens and Rome have captured imaginations—but the real ancient world of Greece and Rome was far from stoic perfection and boundless natural beauty. It was much more like our own: colorful, human, and messy.

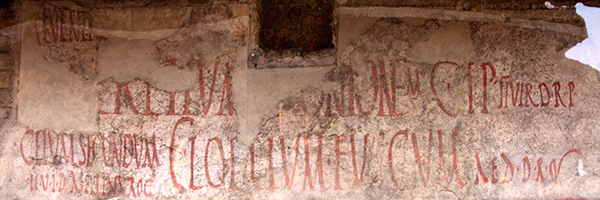

Devoid of Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, the ancient Greeks and Romans found other ways to share their opinions, spout random comments, and have public conversations in the commons. The social media of the ancient world were clay tablets, scrolls, popular books—and of course, walls. In fact, the ancient world was curiously abundant with graffiti.

Bar graffiti 1.0: writing on a wall of the thermopolium (tavern) of Asellina in the ruins of Pompeii. Photo: Amadalvarez, CC BY 3.0

The messages painted on the walls of Pompeii and other cities were sometimes akin to what we find on today’s classroom desks (“Aufidius was here,” “Marcus loves Spendusa”), but they were also quite Twitterlike, rich with pithy tales of love, politics, insults, advertisements, innuendo, and self-expression.

Here are some classic example from Pompeii, which, trapped in the amber of the ash and rock of Mt. Vesuvius, is ground zero for the study of the ancient social.

One-star Yelp review:

“The finances officer of the emperor Nero says this food is poison.”

House of Cuspius Pansa, PompeiiFoursquare checkin w/ BFF:

“We two dear men, friends forever, were here. If you want to know our names, they are Gaius and Aulus.”

A bar in PompeiiFacebook wall smackdown:

[Severus]: “Successus, a weaver, loves the innkeeper’s slave girl named Iris. She, however, does not love him. Still, he begs her to have pity on him. His rival wrote this. Goodbye.”

[Successus]: “Envious one, why do you get in the way? Submit to a handsomer man and one who is being treated very wrongly and good looking.”

[Severus]: “I have spoken. I have written all there is to say. You love Iris, but she does not love you.”

Bar of Prima, PompeiiCraigslist ad:

“The city block of the Arrii Pollii in the possession of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius is available to rent from July 1st. There are shops on the first floor, upper stories, high-class rooms and a house. A person interested in renting this property should contact Primus, the slave of Gnaeus Alleius Nigidius Maius.”

House of Olii, PompeiiBraggy tweet:

“If anyone does not believe in Venus, they should gaze at my girlfriend.”

House of Pindarius, Pompeii

These comments diverge sharply from what is expected from the illustrious civilizations of ancient Rome as they’re depicted in museums. Then again, much of what we see in museums comes from the graves of the wealthy—not an especially comprehensive selection. Regardless of era or region, most people are not wealthy, just ordinary folks whose greatest societal impact might be some writing on a wall. And this invisibility can be a good thing, because it grants them freedom. In Rome, while prominent members of society married to cement political alliances, those in the lower classes could marry for love, rendering necessary the same dating game familiar today.

Speaking of dating, how did the average Roman schlub get relationship and fashion advice before the printing press, TV, smartphones, and the Internet? It wasn’t as available as it is now, but Ovid’s Ars Amatoria and other works did subsist as acceptable substitutes, with recommendations to “take care that your breath is sweet, and don’t go about reeking like a billy-goat,” a true aspiration for all of us.

Here’s how to charm the ladies! Creep up on them naked while they’re peacefully sleeping. Wine Cup with a Satyr and a Nymph, attributed to Onesimos, Greek, 500–490 B.C Terracotta, 12 in. wide (with handles). The J. Paul Getty Museum, 86.AE.607

Here’s another perception about the ancient world that’s just not true: Greek and Roman women were meek and subservient. The abundance of female monsters in classical mythology alone suggests that men knew more about the wrath of women than they wrote in their history books. Even when forced into political marriages, women were able direct policy through their husbands. Livia, the wife of Augustus, spun and wove like a proper, dutiful wife, but wielded much influence over her husband, and was frequently sought as an adviser by many government officials. Though Augustus had three grandsons, it was Tiberius, Livia’s son from a former marriage, who became the next emperor, and she continued to have much power and influence during his reign.

What is known as classical antiquity spanned hundreds of centuries and comprised a mass of regions, classes, and individuals. Any generalization will have its exceptions and discrepancies. This week, we hope to reveal the ordinary side of the ancient world—the irony, politics, expectations, independence, social media, backstabbing, romance, and insolence.

Connect with more “Classics 2.0” content from this week’s Getty Voices:

- Jackie Ibragimov, teen history buff and ViTA, schools us in damnatio memoriae and how his ancient concept is relevant today

- Seduction in Ancient Rome. Thanks, Ovid!

Comments on this post are now closed.