A single telling object in a new Getty Villa exhibition suggests how the Byzantine Empire emerged from, and transformed, classical antiquity

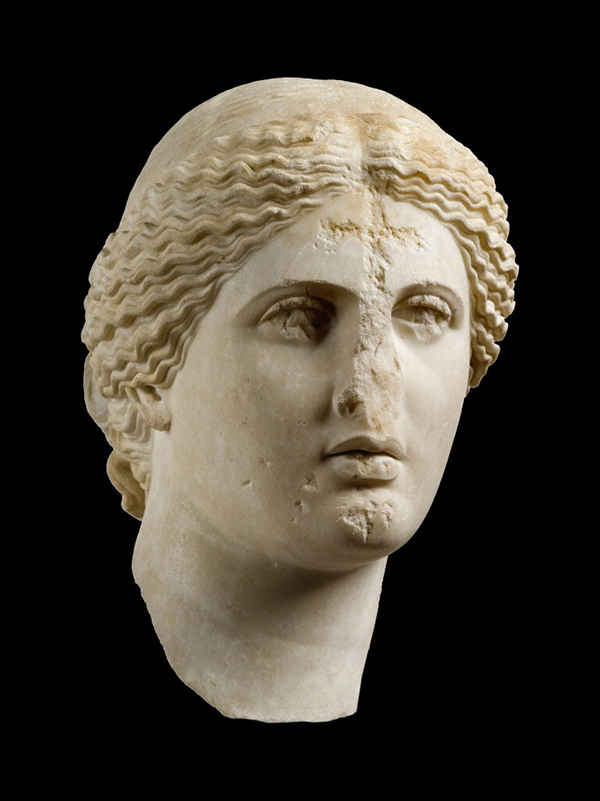

Head of Aphrodite, A.D. 1–100, Roman, made in Athens, Greece. Marble, 15 3/4 in. high. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Image courtesy of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

An exhibition of medieval art may not initially seem to be a natural fit for the Getty Villa, known for its collection of ancient Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities displayed in a replica of an ancient Roman seaside villa. Yet the Byzantine Empire (A.D. 330–1453), whose art is the subject of the exhibition Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections (April 9–August 25), grew out of the forms and philosophies of late antiquity. As the curator of the installation at the Getty Villa, one of the themes I’ve sought to illuminate for visitors is the story of the relationship between the Byzantines—who spoke and wrote in Greek while calling themselves Latins—and their classical past.

Renowned for its rhetorical and philosophical schools, Athens remained a center of classical culture and a stronghold of paganism well into the fifth century A.D., centuries after the political power of ancient Greece had faded. After A.D. 380, when Christianity was declared the official religion of the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman) empire, ancient temples—both on the sacred grounds of Athens’s Acropolis and in the city spreading around it—began to be converted into churches. The Parthenon itself was transformed into a three-aisled basilica by the late sixth century, becoming an important shrine of the Virgin Mary.

The exhibition at the Villa includes important fragments from an architectural frieze decorated with delicate palmette reliefs, which come from a fifth-century apse once built on the Acropolis—perhaps inside the Parthenon itself. They crown the east wall of one of the five exhibition galleries at the Getty Villa and represent an exceptionally rare collection of late-antique treasures from Athens, Corinth, and Thessaloniki.

Head of Aphrodite, A.D. 1–100, Roman, made in Athens, Greece. Marble, 15 3/4 in. high. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Image courtesy of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

One of the many breathtaking objects in the exhibition, this over life-size head of the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite, is a particularly telling example of how closely the classical and the early Byzantine worlds were intertwined from the very beginning. A Roman copy of a Greek original, it is sculpted from prized Parian marble (quarried on the Aegean island of Paros). Broken off from its body, which has never been found, it was unearthed in 1889 near the Tower of the Winds in the Roman Agora of Athens. It is now in the collection of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, one of 34 Greek museums that have generously loaned masterpieces from their collections to the exhibition.

To ascertain the original appearance of the full statue, we look to other surviving sculptures of Aphrodite. When possible, scholars of classical art group similar works into “types,” each of which is defined by specific postures, expressions, garments, and hairstyles. This Aphrodite head belongs to the “Aspremont-Lynden-Arles” type, which has been identified with a work of the famous sculptor Praxiteles, made around 370 B.C. This version survives in several full-scale Roman copies; a well-known one in the collection of the Louvre, shown below, is nearly two meters high, nude but draped from the hips down, much like the famous Aphrodite from the Greek island of Melos better known as the Venus de Milo, which today is also in the Louvre.

Statue of Aphrodite (Venus of Arles), overall view and detail, Roman with 17th-century additions, found in Arles, France. Marble, 96 1/4 in. high. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo left: © 2006 Musée du Louvre / Daniel Lebée and Carine Deambrosis. Photo right: Marie-Lan Nguyen

Depictions on coins offer more clues to our fragmentary Aphrodite: the goddess probably held a mirror low in one hand, causing her to dip her head in order to focus her gaze on her own reflection. Her features carry characteristics of the famous Athenian courtesan Phryne, the notorious mistress of Praxiteles and his model for the first life-size female nude in art history, the famous Aphrodite of Knidos, who also turned her head in the midst of an action. With a small Eros originally at her side, the full statue likely served as an offering to the sanctuary of Aphrodite and Eros on the north slope of the Acropolis in Athens in the first century A.D.

The appearance of the new Christian religion in pagan Athens, with its sanctuaries full of imagery devoted to the Olympian gods, resulted in a clash of cultures demonstrated nowhere more profoundly than on the face of this Athenian Aphrodite. Christians who lived in Athens during the early years of their religion’s establishment hacked at the eyes and mouth, blinding her and rendering her speechless. They also carved a cross into her forehead, marking one of the ways in which people lived with pagan motifs while revering Christ. Yet far from destroying the goddess as a demon from the past, this cross is interpreted as a “repurposing” of her divinity for the use of the new Christian religion. In this way the sculpture could return to its original use as devotional focus in a sanctuary—but in a new religious context.

Marked with the most potent symbol of the new religion, this head symbolizes the fracturing of the classical world during the early centuries of the establishment of Christianity in Greece. As much as Aphrodite was silenced, she speaks very loudly for both eras.

Comments on this post are now closed.