Local conservator Chris Stavroudis and GCI Senior Scientist Tom Learner work on a painting by artist Doug Wheeler.

I popped by the Getty Conservation Institute’s science labs this week to be met with a surprise: a large white Doug Wheeler painting (1964, Untitled, acrylic) alongside the beakers and other scientific equipment. Wheeler is best known for his neon installations (like this one at LACMA), but he began his career on canvas, making soft white paintings with lightly colored edges that look as if they float ethereally off the wall. This was the very last painting he made of that type.

Having a painting in the labs is unusual, because scientists usually go to the artwork for analysis, or bring back microscopic paint samples to analyze. Turns out, the artwork ended up in the GCI science labs as part of the CAPS project—or Cleaning of Acrylic Painted Surfaces initiative, which integrates ongoing research from the GCI’s Modern Paints project and from other research collaborators (including the J. Paul Getty Museum) with the latest art-conservation cleaning techniques. The hope is that this dialogue will aid the application and evaluation of new treatments and guide future research on acrylic painted surfaces.

As part of the collaboration, the painting is being cleaned by local conservator Chris Stavroudis with Jennifer Hickey, a graduate of NYU’s art conservation program, and GCI scientists are undertaking a far more detailed examination of the painting than would normally be possible. The artist himself has visited the lab regularly to view the painting’s progress. The work is ultimately destined to go to the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego for an exhibition in fall 2011 as part of the larger Los Angeles-wide effort Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980.

Conservator Chris Stavroudis cleaning a water stain on the painting by artist Doug Wheeler.

Not having been seen publicly in a number of years, the painting had been in art storage and had gotten extremely dirty. It also had sustained some water damage, resulting in a disfiguring stain down one side. So the artist was faced with a dilemma—to ask a conservator to attempt to clean the painting, or to recreate the surface he wanted by respraying the entire painting himself.

“It was depressing when I first saw it. It was so dirty. I considered respraying it, but respraying it is like doing it all over again and I couldn’t possibly do it right. It wouldn’t be the same thing anymore,” Wheeler told me yesterday.

You’d be surprised how often conservators and artists have to wrestle with this kind of decision when dealing with modern and contemporary art.

“Acrylic paintings with large, monochrome areas of color are notoriously difficult to clean,” admits GCI senior scientist Tom Learner, who leads modern and contemporary art research. “For many artists, a re-created work can seem a lot closer to their initial concept than dealing with the altered condition of the original work. But that brings up all kinds of tough dilemmas for conservators, who want to accommodate an artist’s wishes, but also need to consider the importance of preserving the original materials.”

In this case, Wheeler opted to have Stavroudis try to clean the work, and allowed the GCI team to use the painting as a case study for their CAPS research. The results were phenomenal: the dirt and grime were removed, and even the water stain was reduced to the artist’s satisfaction.

“I want my work to feel like you’re seeing particles of color in the air, very subtly. When I first saw the painting it was dirty, it was all wrong. It feels right to me again,” Wheeler said. “Now it does to me what it should. It has an indefinite kind of presence I was after, which feels really good. The sensibility is there again. I was struck when I saw it.”

Other modern works of art aren’t so easily righted.

“Conservators know a lot about how to clean older paintings, because artists were restricted to a handful of paint types, primarily oils, and there’s a significant body of research and practical experience for them to draw on. But for the last 50 years or so, in addition to a relative lack of research, artists have increasingly used a variety of new materials and techniques,” says Learner. “Because of these materials, some of the objects alter quite rapidly in appearance and then require intervention. These newer materials, like acrylics and plastics, pose a big challenge to the fields of conservation and art history. Much more research needs to be done in these areas.”

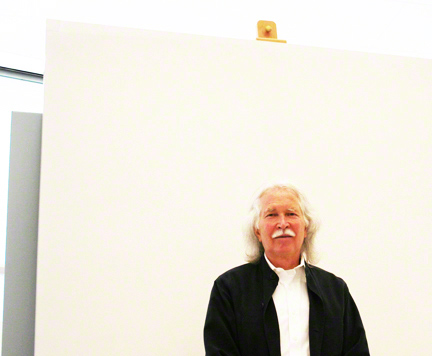

Artist Doug Wheeler at the Getty Conservation Institute science labs.

It’s been said that Wheeler, one of the three key figures who helped create the Light and Space movement (along with James Turrell and Bob Irwin), has been rather overlooked. It’s wonderful that his artwork is again being seen—and in this case, being seen just as the artist envisioned it.

Imperial Clothing, open your eyes, and your souls.

And how come Nuestro Pueblo(Watts Towers) is not included in your Pacific Standard Time? The greatest work of art on the west coast by the toughest, most spiritual creator, yet you show the laziest and most decadent, for those who see what they want to see, and dont feel at all. Imperial Clothing.

For shame.

Hi, Donald.

Thanks for your comment. In fact, Watts Towers is part of the Pacific Standard Time initiative. Here’s the description of the exhibition and events related to Watts Towers:

The Impact of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and the Watts Towers Arts Center

*Two Los Angeles, CA Locations:

Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery (MAG) – December 15, 2011 to February 12, 2012

Watts Towers Arts Center (WTAC) – December 17, 2011 to February 12, 2012

Concurrent exhibitions accompanied by films, lectures, and youth classes will examine the role and influence of the City of Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery (MAG) and the Watts Towers Arts Center’s (WTAC) Noah Purifoy Gallery in nurturing the burgeoning arts sector in post-war Los Angeles. Founded in 1952 (MAG) and 1965 (WTAC), when the current environment of public and private museums and galleries was not yet developed, MAG and WTAC demonstrated an early commitment to the work of local artists, particularly women and people of color, many of whom are now renowned, such as Betye Saar and June Wayne. In addition, notable artists including Vincent van Gogh, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Charles Wilbert White were first exhibited in Los Angeles through these institutions.