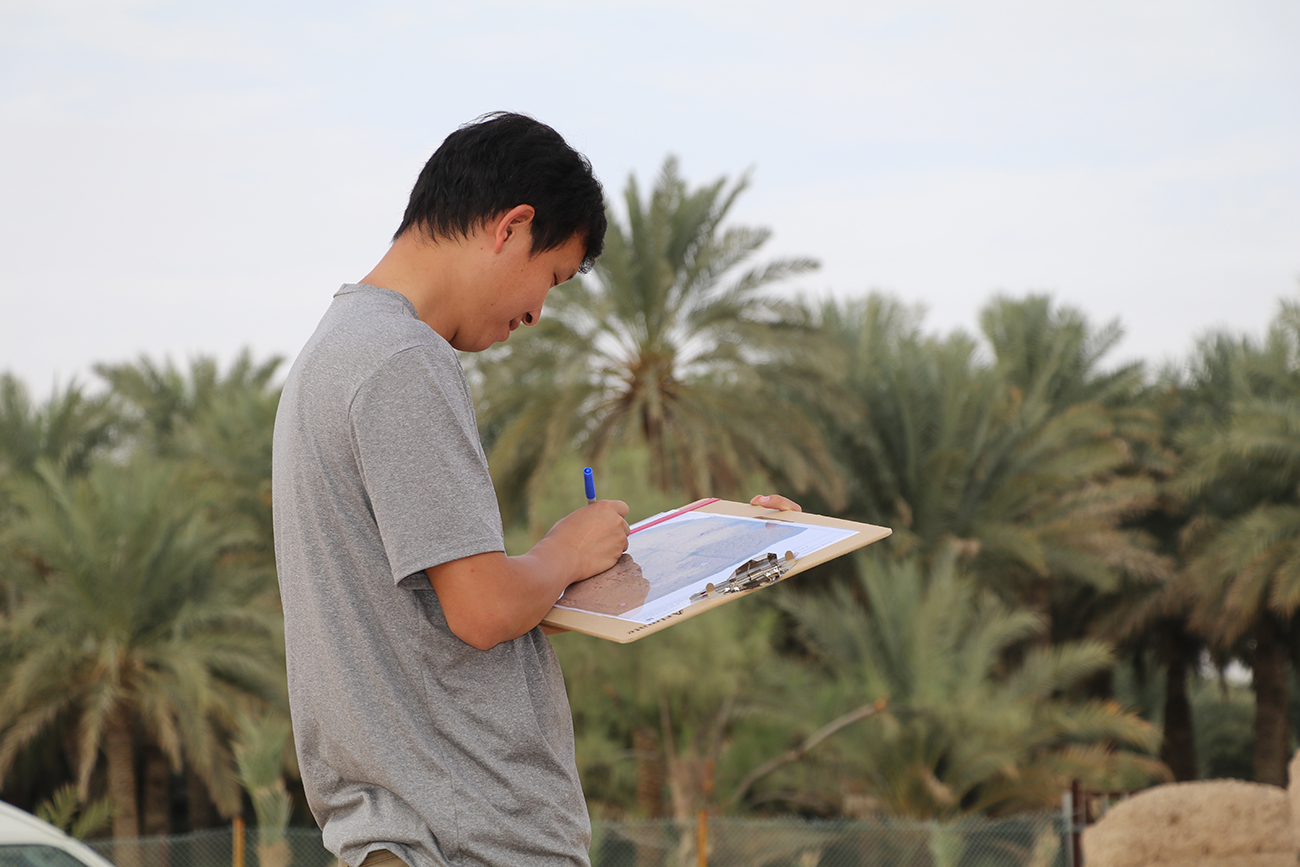

Cui Biao collects samples for microbial analysis at an earthen site. Courtesy of Cui Biao

People across the world have used earth, clay, and other such materials to construct buildings for thousands of years, from ancient times to today. These earthen structures exhibit a huge variety in size, style, and building techniques.

Training opportunities in best practices of earthen architecture conservation, especially those addressing earthen architecture in the Middle Eastern, North African, and South Asian regions, are greatly lacking. A monthlong course held in October 2018 in the World Heritage City of Al Ain in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi was a rare opportunity for professionals to spend four weeks immersed in the conservation of earthen architecture. Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and the Department of Culture and Tourism–Abu Dhabi, the course brought together architects, engineers, archaeologists, and conservators from the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia responsible for the care of earthen structures to further their knowledge in current best practices and to help build a global network of experts.

Early in the course Angela spoke with several participants to hear about the particular challenges they face back home in working with earthen architecture and what they hoped to learn from the course. Each cast light on the diversity of earthen building techniques and types and the specificity of conservations issues they face, as well as on their shared sense of the urgency and importance of this work for preserving their cultural heritage.

Cui Biao – Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, China

Cui Biao has been an assistant researcher at the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology in southeastern China since completing a master’s degree in archaeological sciences. His work focuses on the protection, research, and management of immovable cultural heritage.

Why is earthen architecture important to you?

I think it’s fate. When I was an undergraduate at Peking University, my mentor, A.P. Zhou Shuanglin, was an expert in the conservation of earthen sites. Under his guidance, I participated in consolidation of a clay wall at Locality 2 of the Zhoukoudian site, through which I gained knowledge and experience about the conservation of earthen heritage. Now, I work on projects every year that involve the conservation of earthen architecture and sites.

What do you do at the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology?

The Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology manages all aspects of conserving the immovable cultural heritage resources in our province, including archaeological surveys, exploration, excavation, research, and technical management.

My department—the Department of Conservation—conducts research, evaluates practices, and organizes training for practitioners in our province, among other things.

What types of earthen heritage are you responsible for?

Testing trinity-earth samples for the purpose of restoration. Courtesy of Cui Biao

There are three main types of earthen heritage in our province. The first is traditional earthen wall architecture. In many mountain villages in our province, there are a large number of traditional buildings with walls made of rammed earth.

The second type is archaeological sites. We have three national and 15 provincial archaeological parks in our province, most of which include the in-situ exhibition of an earthen heritage site.

The third type is rammed trinity-earth forts, which are located in the coastal area. Most of them were built from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries and were built from a specific earthen material—a mixture of yellow clay, sand, lime, and probably a small amount of organic additives. There are about 10 such forts in existence.

What types of conservation challenges do you face in your work?

The first is a lack of research. Every building has its own unique materials and was built with different methods, so we have to figure those out through adequate research before conservation and restoration, otherwise there will be great damage to their authenticity.

The second is improper interventions. For example, a decade ago polymer consolidating and waterproofing materials were used liberally in the conservation of a rammed trinity-earth fort. Looking at the fort now, there is a lot of flaking caused by the accumulation of the polymer materials on its surface.

The third issue is the environment. Many archaeological sites exist in wet conditions—the nearby water table is very high, which causes a lot of deterioration. If we only deal with the site itself and don’t improve the overall environment, it will not solve the fundamental problem. However, in most cases it’s difficult to isolate the site from the groundwater.

What are the greatest threats in your region to earthen architecture?

The greatest natural threat is water—definitely. Our province is located in the southeast coastal area of China, and the climate is very humid and rainy, especially in summer, which means a lot of trouble for earthen heritage.

Another great threat comes from people. We are one of the most developed regions in China. The pace of urban and rural construction is very fast and many underground archaeological sites have been damaged or cannot be protected in-situ, and many earthen residences in mountain villages are uninhabited and have not been maintained for a long time.

What aspects of your region limit the impact your work?

The conservation of earthen heritage is a specialized field, especially in such a wet and rainy region. Although we have a lot of conservation institutions and companies in our province, most of them don’t have qualifications and capabilities in this field. So, when we want to implement an earthen site conservation project, we have to find an outside team to do it. In many cases, these teams are not willing to work far from home, and their experience may not apply to our situation because of the diversity of the environment, material, and craft. Many projects have been shelved for a long time or have not achieved very good results.

Lack of funding is also a limiting factor sometimes. In China, conservation funds mainly come from government financial allocations. The economic development in our province is not very balanced. In some regions with poor financial conditions, it is difficult to do much heritage conservation.

What skills or knowledge do you hope to get from this course?

What I most want is hands-on practice with the materials, building processes, conservation, and restoration methods.

It’s also a valuable opportunity for me to learn international theories, methods, and practices in the conservation of earthen heritage, and it can help me and my institution to establish exchange and cooperation relationships with institutions in other countries.

During the earthen architecture course, Cui Biao participates in a survey exercise at the site of Bin Jabr, Abu Dhabi.

I’m planning to find a suitable site in our province to apply the knowledge I have learned in this course by carrying out a small-scale, experimental, but systematic conservation project, completing the preliminary research, documentation, design, and implementation personally. After that I will track and monitor its effects, summarize it into a research report, and then make it a demonstration case to my colleagues and peers in our province. I will apply for funding from the Provincial Bureau if possible. This work will take a long time, but I think I will do it.

Do you have a favorite building or site?

The Liangzhu Archaeological Site is my favorite. It is located in the northwest of Hangzhou City. The site group includes a fortified city dating from 3,300–2,300 BCE, accompanied by an impressive system of earthen dams for flood control and irrigation. An earthen platform in the center of the city probably supported a palace complex, and grave goods from the adjacent Fanshan cemetery include finely worked jades that accompanied high-status burials. It has been widely recognized as evidence of 5,000 years of Chinese civilization, and will be nominated for World Heritage listing in 2019.

Liangzhu National Archaeological Park. Courtesy of Cui Biao

There are many amazing earthen structures in the site group. The most worth mentioning are the dams, which are part of the peripheral water conservation system of the Liangzhu Ancient City. The structure of the dams is very special; they were built with thousands of oval-shaped, straw-wrapped silt blocks, which are a bit similar to modern sandbags.

Traces of straw-wrapped silt blocks on a section of Laohuling Dam at the Lianghzhu Ancient City site. Courtesy of Cui Biao

We also unearthed some sophisticated burnt earthen walls in the Liangzhu Ancient City, which showed the superb architectural skills of that time. Liangzhu Archaeological Site provides me with many objects for studying earthen building materials and techniques in the Neolithic age, so I like it very much.

_____

Read an interview with another participant in the earthen architecture course who works in Oman.

Comments on this post are now closed.