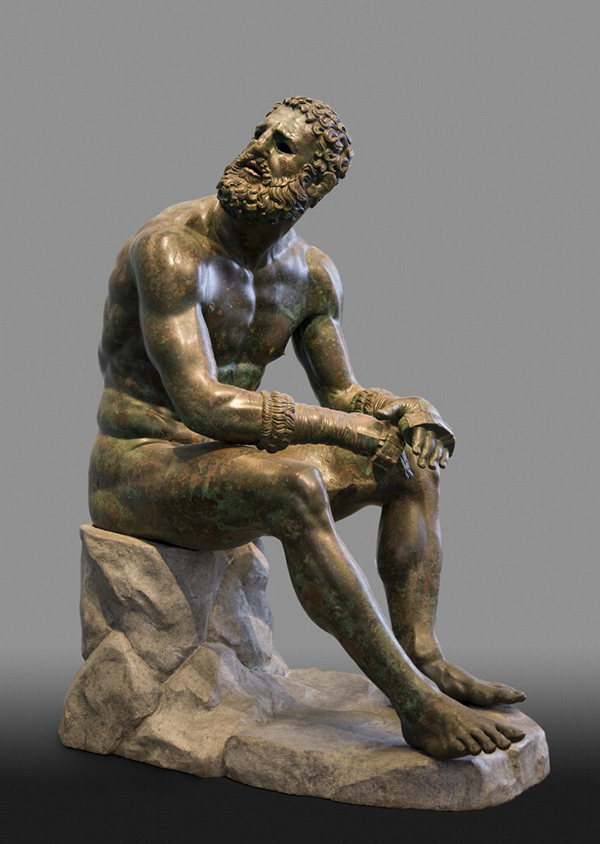

Seated Boxer, “The Terme Boxer,” 300–200 B.C. Bronze and copper, 140 cm high. Museo Nazionale Romano—Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome. Su concessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo—Soprintendenza Speciale per il Colosseo, il Museo Nazionale Romano e l’area archeologica di Roma. Photo © Vanni Archive / Art Resource, NY

The Seated Boxer is one of the most admired ancient works of art. Since it was found in 1885—on the slopes of the Quirinale, where the Baths of Constantine stood—the sculpture has provoked intense debate.

Its date and maker remain unknown. Some were initially deceived by the inscription “Apollonios Nestoros” (Apollonios, son of Nestor) found on the left glove in 1927. Others date the work to the end of the 4th century B.C., attributing it to the sculptor Lysippus and his school. Still others have considered it to be a product of the 1st century B.C., attributing it to an unknown sculptor capable of mixing different styles and sensibilities.

And who is the figure? Some have identified him as the Boxer of Quirinal, who won at Olympia for the first time in 336 B.C. following a gruelling career of continuous defeats. Others say he is Polydamas, an athlete of legendary strength who was born in Tessaglia and then called to the court of Persia by Darius II. Yet others call him a historic figure or a heroic mythical one.

But whether the sculpture represents a winning athlete or a loser who unexpectedly claims victory at the end of his career, whether it portrays a historic person or a legendary hero, the thing that matters to us—that has always attracted us—is the transcendent tiredness that oozes out of him. He is a magnetic presence in the exhibition

Seated Boxer (detail), “The Terme Boxer,” 300–200 B.C. Bronze and copper, 140 cm high. Museo Nazionale Romano—Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome. Su concessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo—Soprintendenza Speciale per il Colosseo, il Museo Nazionale Romano e l’area archeologica di Roma. Photo © Vanni Archive / Art Resource, NY

Shown by the artist in the act of turning his head when something special is happening (the Greek concept of kairós), the boxer is seated, profoundly marked by deep cuts and copious bleeding all over the right side of his body. We don’t know what that turn of the head means: has he perhaps just heard the referee’s decision? Another call to fight? Is it a look at the excited crowd? Or perhaps a mute questioning of Zeus in search of some answer? The numerous controversies unleashed in the attempt to explain that gesture have informed all the mystery and poetry that has surrounded him, all the seduction of the work.

In composing a poem inspired by the Boxer, it was natural for me to speak of that moment from his point of view. I decided to do so without opting for one interpretation or another. Every time we analyze a work we profane it, we attack its irreducibility. Poetry should never be reduced to explanation. Real poetry always moves beyond any calculation, any system, any geometry: it is incompleteness, evocation, lament, shiver.

Before writing “Boxer” I could do nothing but sing of his fragility and solitude; of the weight of his dramatic life and the tragic sense of death, of banality, that belongs even to ancient masterpieces we would wish to be eternal. The uncertainty that has often surrounded their attribution, the mutilated and fragmentary condition in which they have almost always come down to us from antiquity, gave me the cue to speak of the transience of life, of every one of man’s works, of the meaning of time.

“…All that is body is as coursing waters, all that is of the soul as dreams and vapors. As for life, it is a battle and a sojourning in a strange land; but the fame that comes after is oblivion,” wrote Marcus Aurelius in his Meditations. A slow fall into forgetting, indifference, the inorganic: not even our great works are immune, despite our desperate attempts to preserve them.

“The Boxer,” Part I

Poem by Gabriele Tinti, read by actor Robert Davi in the galleries of Power and Pathos at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Videos created in collaboration with the Italian Cultural Institute of Los Angeles.

Gabriele Tinti@Robert Davi reads “The Boxer” Part I – Getty Museum from gabriele tinti on Vimeo.

“The Boxer,” Part II

Poem by Gabriele Tinti, read by actor Robert Davi in the galleries of Power and Pathos at the J. Paul Getty Museum

Gabriele Tinti@Robert Davi reads “The Boxer” Part II – Getty Museum from gabriele tinti on Vimeo.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks