Xanti Schawinsky teaching a portraiture class, in an undated photo by Helen Post Modley. Image Courtesy of Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina, Asheville.

“It must have been so much fun to be at Black Mountain,” a friend said the other day. She’d been up to Boston for the Leap Before You Look show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, the show now open at the Hammer Museum in L.A.

The exhibition documents the amazing achievements of students and teachers at a tiny experimental school called Black Mountain College, improbably functioning from 1933 to 1957 in the mountains of western North Carolina. Day by day, over years, innovators as diverse as Bauhaus-trained painter Josef Albers and American poet Robert Creeley found space there to explore possibilities of their own work and to collaborate in providing an education with art at the very center.

Today, names like John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jacob Lawrence, Willem de Kooning, Anni Albers, Charles Olson, and Buckminster Fuller are touchstones in the worlds of music, dance, art, crafts, poetry, design.

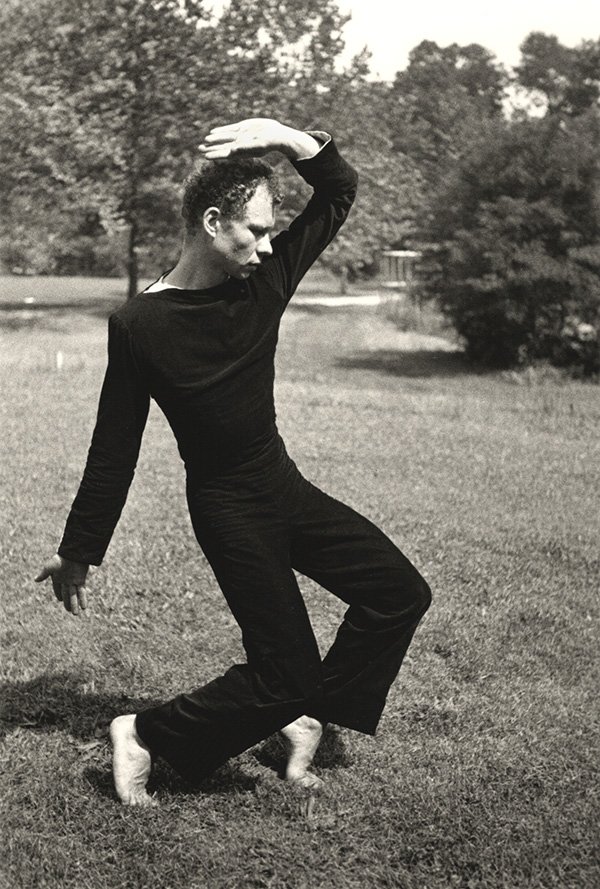

Hazel Larsen Archer, Merce Cunningham Dancing, c. 1952–53. Image courtesy of Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center

Knot 2, 1947, Anni Albers. Photographed by Tim Nighswander/Imaging 4 Art. Image copyright the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society New York

In 1955, the summer I was 18, most of Black Mountain’s “names” were barely known, let alone celebrated—and while I did have fun, I encountered something far more serious.

1955 was the dark ages. Especially in the South. Chapel Hill, where I lived, had just one bookstore, one record store. No black people went to the university. Carrboro, right next door, wasn’t known for roots music. It was a hardcore Southern mill town, rigidly segregated as everything was. At the mill, black men got janitor and loading jobs only.

Hypocritical standards for female behavior loomed everywhere. Being liked by boys was the highest achievement open to young Southern white women. Thus I was inured to a “boys won’t like you if…” refrain. If you don’t wear lots of lipstick. If you talk too loud. If you argue. If you get known as “easy.” If you don’t.

Education had a clear, stay-in-line structure, including the unspoken instruction for women: Be sure to catch a husband by graduation time. Women could not even attend the university at Chapel Hill until their junior year, and the flood of co-eds entering from the women’s branch in Greensboro seemed singularly devoted to husband-seeking. I found a few exceptions in university art classes, which I was able to take while I was still in high school, because my father was on the university staff. (He was director of the University of North Carolina Press.)

Small wonder I was sulky, resentful, and, despite a few small adventures, very, very lonely.

Then one June day I was on a Trailways Bus bound for the summer session at an obscure place called Black Mountain College. I’d learned of it through The Black Mountain Review magazine in the university library. But I’d been given wildly diverse descriptions from everyone I asked. “Is it still open?” “Full of communists and Negro lovers!” “It might be interesting for you. Is Eric Bentley (a New York theatre critic) still there?” (He had been, in the early 1940s. Not any more.)

I wasn’t sure the place I was headed to was even real. But I’d been informed the school dining hall was closed, so stuffed in my duffle bag was a one-burner hot plate and a small iron frying pan liberated from my mother’s kitchen.

Two students in a rust-bucket car were at the bus stop to pick me up. The red-haired one just drove. The other, in a flat Boston accent, talked on and on. There’s a big party tonight to kick off the summer. You have to come. You’ll meet everyone. You’ll be shocked at how big Charles Olson is. Six foot seven. And he rattled on about an amazing work called The Maximus Poems that Charles Olson was in the midst of writing. I’d seen Olson’s name in The Black Mountain Review, where his writing and that of others had shocked and intrigued me.

He said I could choose my classes when I talked to Charles, who was head of the school, and Wes Huss, the theater teacher and school treasurer. Nothing was assigned, he assured me. Nothing was required. I could ask for tutorials. I could come and go as I wanted. All the studio art classes were taught by a painter, Joe Fiore. Other painters from New York were sure to visit later to review graduation shows. That was how it worked. If, and he said it was an “if,” one worked for graduation. Lots of people didn’t. A person could simply work. Like real life.

He laughed.

Black Mountain, Lake Eden, 1954, Joseph Fiore. Image courtesy of Asheville Art Museum, Black Mountain College Collection

I was reeling after the five-mile drive. We stopped at a gravel turnaround at the entrance to a fabulously austere, long, white building, resting like a ship by the side of a small lake. The Studies Building. “Students built it,” my impromptu guide reported breathlessly, dragging my duffle into the small entryway.

“Your education belongs to you,” Charles Olson began. He was in his office along with Wes but sunk into a butt-sprung easy chair, the springs of which may have been on the floor. I had no sense of his size.

“You are responsible for what you want to do here,” he told me.

The more I thought about that, later that day and beyond, the more dazzling and more frightening it became. What did I want? I had come for the summer just to get away from home. Suddenly there was more to it. Where did I want to be? And why? No one had ever asked me. Unlike most of the people I’d meet that summer, I had never asked myself. But they had. It was a startling difference even from the arty UNC students I knew.

By 1955, almost everything material at the school was broken, run down, disintegrating. The single washing machine on campus was marked “fuckt.” Lorraine and Mona, down the hall from my room in a large cottage named Streamside, showed me a “stomp in the bathtub” washing method that was kind of fun and passably effective. Clothing didn’t require a lot of laundry skills. Students wore Mexican shirts, torn jeans, handmade earrings. A foretaste of hippie fashion. Many wore the sandals that one of the art students made, strips of rubber crossing over the top of the foot securing sections of tire tread for soles.

How could a whole world open up for me in such a derelict place?

But it did. Everywhere I was confronted by radical departures from the self-assured liberal world I’d grown up in. In Charles Olson’s reading list. In music theory with Stefan Wolpe and theater with Wes Huss—we did scenes by Lorca and Beckett. In Joseph Albers’s color theories, conveyed by a former Albers student, Tony Landreau. Most of all, in constant exchanges among teachers and students—about how nothing is ever truly nothing in art, or poetry, or theater; about giving oneself permission to try anything; about detecting and avoiding the predetermined.

Tenayuca, 1943, Josef Albers. Photographed by Ben Blackwell. Image courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase with the aid of funds from Mr. and Mrs. Richard N. Holdman and Madeleine Haas Russel, copyright the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society, New York

I was at BMC only three months. But a practice of “cut to the chase, go for what you really mean, use any means you can enlist to do that”—what my fellow students called “the Black Mountain brainwash”—left me unable to adapt to the rules of conventional education. I remember thinking I’d be involved with Black Mountain ideas for the rest of my life. I wasn’t mistaken.

The exhibition at the Hammer Museum focuses on the college’s formal dates of operation. But, in my experience, the daring that animated BMC continues to leap. There are still some surprises from its last generation awaiting a wider public look. Poets John Wieners and Edward Dorn. Painters Tom Field and Basil King.

A photograph of the Studies Building at Black Mountain College on a 2014 tour. Photo: Vincent Katz

Only last year, artists from the indie rock groups Arcade Fire and The National collaborated on a multimedia “Black Mountain Songs” in Brooklyn and London, incorporating poetry, painting, dance, theater, and music animated by Black Mountain’s examples.

What galvanized that small group of misfits and mischief-makers, what required people who stayed at Black Mountain to be alive to the unexpected—this has a life beyond the dates that bracket the College’s existence.

“Onward,” as poet Robert Creeley—a teacher at Black Mountain—put it.

Text of this post © Zócalo Public Square. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.