Although two centuries apart, J. Paul Getty and Louis XIV were certainly kindred spirits. Both were rich and powerful, both had lavish residences, and both had huge repositories of art amassed with an obsessive passion for all things beautiful. And what began as collecting ultimately turned to supporting the arts, as we see in the legacy both of Versailles and of the Getty Center and Getty Villa.

One of the highlights of the Getty Museum’s decorative arts collection is its exquisite tapestries, some of which were owned first by Louis, and then later acquired by Getty. The finest and most sought-after of these were created by the Gobelins Manufactory in Paris. When Louis shifted from collector of old tapestries to patron of new ones, he set his sights on making the original Gobelins factory, established by Francis I, into an “art super factory.” With additional land purchased by Louis’s minister of finances, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, and under the artistic supervision of royal painter Charles Le Brun, who served as director and chief designer from 1663 to 1690, the Gobelins had many departments and workshops dedicated to different aspects of furniture and tapestry making.

![Gallery of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu in 1974, displaying French decorative arts. Design: Langdon and Wilson. Photograph: Julius Shulman. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.R.10 [Job 5123]](http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/files/2016/06/gri_2004_r_10_b359_f06_001-r.jpg?x45884)

Gallery of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu in 1974, displaying French decorative arts. Design: Langdon and Wilson. Photograph: Julius Shulman. The Getty Research Institute, 2004.R.10 (Job 5123)

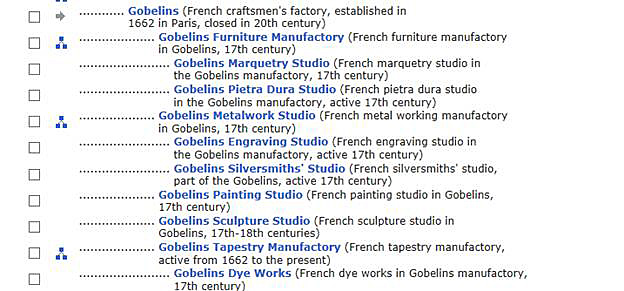

The Getty Union List of Artists Names (ULAN) is a great way to find out more about tapestries’ creators. Housed at the Getty Research Institute, ULAN is a structured vocabulary containing names and pertinent information about artists, architects, corporate bodies, and others involved with the production and collection of art and architecture.

When you look up a name in ULAN, you will find given names, pseudonyms, variant spellings, names in multiple languages, and names that have changed over time. ULAN also includes thousands of names of patrons, monarchs, and sitters, many of which are linked to their corresponding artists.

Allegorical Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, 1664, Philippe de Champaigne. Engraving, 20 1/2 x 29 1/16 in. The Getty Research Institute, 2003.PR.20

The ULAN record for the Gobelins is displayed as the top “governing body” in an indented layout to represent the Gobelins Tapestry Manufactory as one of its subdivisions or “children” (in database terms), and the Dye Works as a smaller division within it.

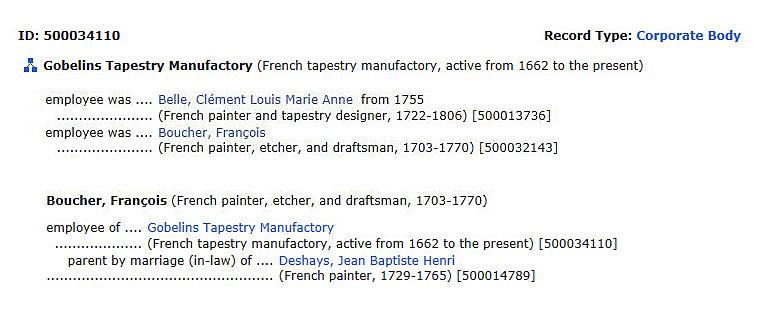

Exploring the record further, we find the names of artists and craftspeople who worked for the Gobelins through associative relationships. We can also uncover important connections such as a father and his sons, a corporate body and its employees, and a factory and its workers—with the “reverse” relationships, such employee and employers, shown in the individual artist’s record.

The example below shows the relationship of François Boucher to the Gobelins, the Gobelins’ relationship to Boucher, and the familial relationship to Jean Baptiste Henri Deshays, Boucher’s step-son.

In the galleries you can explore objects at this time and place—and in the database you can go deeper by tracing the relationships of artists and their patrons, members of artists’ families, art collectives and their members, and more. It all weaves together to create a whole…much like a tapestry.

Comments on this post are now closed.