The bestiary, a medieval book of animals both real and imagined, was one of the most popular books in medieval Europe. Detailed illustrations and descriptions of real yet unfamiliar animals like whales and elephants shared the page with those of imaginary creatures like unicorns and dragons. But the fantastical and allegorical stories in the bestiary didn’t live in the books alone—the images and stories of these animals often escaped from the pages to inhabit an array of objects and works of art, from water vessels and game pieces to enormous tapestries and painted ceilings. And these stories continue to inspire artists into the present day.

In this episode, curators Elizabeth (Beth) Morrison and Larisa Grollemond discuss the exhibition Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World, which brings together one-third of the world’s surviving Latin bestiaries as well as art objects from the Middle Ages through today that were inspired by these books.

More to Explore

Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World exhibition

Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World publication

Book of Beasts blog series

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ELIZABETH MORRISON: Lions and unicorns and dogs and cows and manticores and phoenix were all evidence of God’s creation and His wondrous powers. And so that was the important thing.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Beth Morrison and Larisa Grollemond about their exhibition Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World.

Bestiaries were one of the most popular book types in Northern Europe from around 1180 to 1300. They portrayed not only imaginary creatures, such as the unicorn, the siren, and the griffin, but also beasts like the tiger, the elephant, and the ape. A current exhibition at the Getty Museum explores the beauty, history, and cultural meaning of bestiaries in the context of the medieval world and their continued relevance for artists today.

I’m in the exhibition galleries in the Getty Museum with Beth Morrison, senior curator of manuscripts, and Larisa Grollemond, assistant curator. We’ve come together to discuss the Getty’s exhibition, Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World.

Thanks for your time, Beth and Larisa, and congratulations on your beautiful and stimulating exhibition. Now Beth, you begin the exhibition with this narwhal tusk, which you describe in the exhibition catalog as having been commonly believed during the Middle Ages to be the horn of a unicorn.

Tell us why you begin the exhibition this way and what was so intriguing about the unicorn during the Middle Ages.

BETH MORRISON: We originally thought we really wanted to start the exhibition off with a bang. And everyone knows of the unicorn. Everyone thinks of it as a medieval animal. And so we thought it would be a perfect way to introduce visitors to the idea of the bestiary and beasts in the medieval world.

CUNO: What kind of access did they have to a narwhal?

MORRISON: So it’s interesting. We had a unicorn expert here last week.

CUNO: There is such a person?

MORRISON: Yes. We did have a unicorn expert here last week. And he was telling us about the fact that narwhals often beach themselves off the coast of Greenland. And they would die at some point of the year that was inaccessible, and then the sailors would be able to get there later, when the carcasses had decayed.

And so it’s possible that they found these horns and they thought they were unicorn horns and brought them back to Europe. It’s also possible that they knew that unicorn horns were very valuable, and so they brought them back as well.

But people wanted unicorn horns because they thought that they had magical medicinal qualities. So they thought that it could detect poison or that it could be ground up and drunk and cure you of various ailments. And of course, because unicorns were known to be so elusive, they were a very high-value product. Just like today, when we want items that aren’t very available, they tend to go up in price.

CUNO: And when you say unicorns were elusive, that’s because they didn’t exist.

MORRISON: Yes. And we get the question a lot about, like well, how did possibly people in the Middle Ages believe in unicorns? And what I always tell them is a kind of twofold answer. One is of course, they didn’t have Wikipedia, they didn’t have zoos, they didn’t have transatlantic flights going to Africa every day of the years. And so they didn’t have access to information the way that we do. And so if you think about the fact that they were never going to see a lion, they had never seen evidence of a lion, it was the same for the unicorn.

The other thing that I always say is I don’t think they really cared in the way that we do about facts and scientific truth. It was a different mindset. And for them, lions and unicorns and dogs and cows and manticores and phoenix were all evidence of God’s creation and His wondrous powers. And so that was the important thing.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, describe the unicorn to us. Because it’s been carved. And what purpose would the carving have?

MORRISON: Yeah. So this is one of the few carved so-called unicorn horns that survive from the Middle Ages. And we picked this one because it’s beautifully masterworked. So you can see that the artist has added animals and humans and vegetal matter that twists around and kind of gives that sensation of the twisting unicorn horn which we think of.

CUNO: Would the tusk itself have been displayed somehow in a house or room? Or what would be the function of it?

MORRISON: So we know that this particular one was kept in a church treasury, and was probably used as a candlestick. It’s actually probably one of a pair. The other one we also know exists in a different museum collection. And yes, they probably would’ve been carried in church processions and show the sort of power of the church, that they could have something as elusive and valuable as a unicorn horn.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, this beautifully carved ivory make us want to go walk over here to this saddle, which is a ivory saddle, intensely carved and beautifully carved, with and references to the bestiary. How would this have been used? Larisa?

LARISA GROLLEMOND: So we have a lot of evidence that these saddles were used for ceremonial or processional use. You can see that it would’ve been quite uncomfortable to sit on, probably. There are all of these different panels of really finely carved bone. And to be honest, there’s not a lot of wear in the places that you would expect wear for a saddle. So we think that this was probably used for ceremonial purposes.

What’s interesting about this saddle is that this is a fifteenth century object. And so you can see the story of the unicorn kind of in the center of the saddle there, with the unicorn looking back over his shoulder at the maiden. And this is iconography that would have been familiar from centuries and centuries of repetition. But the unicorn becomes wrapped up in other ideas of romance and chivalry. And so you often see the unicorn story kind of repurposed to go along with romantic scenes or chivalric scenes.

MORRISON: And of course, the unicorn, according to the medieval bestiary, had a very religious meaning. I’m not sure if you know the story of the unicorn. So I think today, we think of My Little Pony and sparkles and all sorts of joyful things. But the story in the bestiary is a little bit darker. So the story is that the unicorn is a savage and noble beast. And of course, everyone wants it for its horn.

But the only way to capture it is to put a young maiden in the woods by herself, and the unicorn will be attracted to her and will come and lay its head in her lap, get a little sleepy. And that’s when the hidden hunters jump out from behind the trees and can kill it and carry it back to the palace of the king. And so a lot of people think, well, that’s a little dark for a unicorn.

But the idea is that God put secret-coded hidden messages in the animals at the beginning of time. And the unicorn is a good example, because he wants to tell his story for the Earth. And that includes, of course, the idea of the Virgin Mary and the incarnation. So the unicorn is like Christ, who leapt into the lap, into the womb, of the Virgin Mary. And then when she gave birth, he became human, which made him vulnerable to death for the first time. And that’s the death of the unicorn.

CUNO: Yeah, and that’s what we see over here, enacted in this tapestry. Is that right? Because we see a walled garden, we see a unicorn coming up to Mary, I suppose.

MORRISON: Yeah. So this is a fabulous tapestry from the National Museum in Switzerland. And this actually makes the unicorn’s tie with Christ and the Virgin Mary very concrete, in that you can see the maiden, who as you mentioned, is depicted in this beautiful enclosed garden with all sorts of flowers, actually has a halo and is identified as the Virgin Mary, with a blue robe.

And the unicorn—and he’s polka dotted, which is fabulous. And he’s leaping into her lap. And then you can see that the hunter is killing him. And you’ll notice that the spear is often going into the unicorn’s side, just as the spear entered Christ’s side during the crucifixion.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, Larisa, tell us about the bestiary itself. So why did the bestiary, a book of animals in which the unicorn was sometimes featured, become so popular during the Middle Ages? And is it fair to describe them as popular? I mean, how did the public see bestiaries or hear the stories they comprised?

LARISA GROLLEMOND: So the bestiary is one of the most popular books of the Middle Ages. And we know that because many copies still exist, of course, and they’re often the most luxuriously illustrated versions of that text. So we think that they were originally used in monastic contexts, and created by and for monastic audiences. But of course, the images are so stunning, so engaging that they would’ve been equally popular for a secular audience. And so we actually don’t know the original patrons of many bestiary manuscripts, but we do think that they would have been equally popular kind of in religious circles and in secular circles.

CUNO: To read by an individual? Or to be read out loud by an individual to a group of individuals?

GROLLEMOND: That’s a good question. So there’s actually evidence in one of the bestiaries in the show that the book was turned opposite the person who was holding it. We actually have evidence of thumbprints on the top of the page, which indicates that an individual was actually turning it away from him to show people. And so because the animal stories are kind of easy to understand and really engaging, they were really easy to use to remember these complex religious stories.

And so we do think that they would’ve been shared among a monastic audience in that context, certainly. And I think with the secular audience, equally so. You might have read this as an individual, or you may have read it in a group.

CUNO: Now, these bestiaries are so beautiful and they are so richly illuminated—that is, illustrated, we might call them today. And so they would’ve been prized possessions by a few people for a few people, I should think. So but not popular in the sense they would be shared broadly with a mass of people.

GROLLEMOND: Absolutely. But we also think that they would have been used for sermons, for preachers putting together sermons for the lay public. And so the material from the bestiary is actually being circulated orally, also.

CUNO: Beth?

MORRISON: I just wanted to add that as you’ll see throughout the exhibition, it’s not only that the beasts and their stories appear in bestiaries, but they appear in all these different kinds of objects. And these objects would’ve been much more available to a wide public. They would’ve noticed the images, which don’t have a textual component; they would’ve just known the stories.

And I often compare them to a medieval version of memes. They were imagery that everyone was familiar with. And so you could recognize it no matter what kind of context, even in public contexts.

CUNO: Yeah. Well I think the visitor to the exhibition will be surprised to learn that the exhibition comprises maybe the largest number of bestiaries ever gathered in one place at one time, and maybe one-third of all known bestiaries. Is that because so many had been lost or because there weren’t so many to begin with?

MORRISON: Believe it or not, from the thirteenth century, sixty-two copies of a single text is actually a large number to survive. We know that the vast majority of medieval manuscripts have been lost over time.

CUNO: And there are sixty-two known bestiaries?

MORRISON: There are sixty-two known illuminated Latin bestiaries. And we have twenty-four here in the exhibition, so it is over one-third. Now, when you’re thinking about Bibles, of course, in the thirteenth century, there were hundreds and probably thousands of illuminated Bibles. But that was the most popular kind of text in the Middle Ages. So for a little bit less-circulated text, this is pretty popular.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, Larisa, tell us about the earliest bestiaries. And what were their sources?

GROLLEMOND: The first books that we call bestiaries really appear around the year 1100. And the bestiary text is an amalgamation of all kinds of different texts. So the core text is actually a second century text known as the Physiologus, which just means the naturalist. And this text actually comprises dozens of animals. And as the text gets adopted, other texts are added to it. And so when it becomes the bestiary in the Middle Ages, it actually comprises not only the Physiologus text, but also excerpts from Isidore of Seville, the great encyclopedist as well as Silenus and Pliny. So the bestiary as we know it in the Middle Ages is kind of an amalgamation of a lot of different Classical texts.

CUNO: And Physiologus, tell us about that text. Where does it come from?

GROLLEMOND: That’s a great question. So the Physiologus, we don’t know the author of that text, but the bestiary refers to it as “The Physiologus.” So Physiologus says that the lion is the king of beasts, et cetera, et cetera. And we think that it was composed in the second or third century. It’s a Christian text. And so the idea that animals were Christian allegories is already present in that foundational text.

CUNO: Were there set animals in every bestiary?

GROLLEMOND: No. So the bestiary is quite a flexible text. It doesn’t include a set number of animals, although you do see animals recur throughout many versions of the text, the most popular ones. Bestiaries can have anywhere from a few dozen animals to over 200 animals, depending on the version of the text that you’re reading. As I said, you will always see the lion and the eagle and the dragon and kind of the main animals; but then there are a lot of accessory animals.

MORRISON: And one of the interesting things about the Physiologus, as Larisa mentioned, it is a Christian text. So all those animals that were included in the original Physiologus have this sort of Christian hidden meaning that we talked about. But as other animals got added from these other kinds of texts, including encyclopedias and Classical natural history texts, of course, those animals didn’t have Christian meanings.

So sometimes the reader maybe just was sort of amazed at reading about these animals and didn’t need the Christian context, or perhaps was encouraged to kind of come up with a Christian moral lesson on their own.

CUNO: So you write in the catalog that from about 1180 to 1300, bestiaries were among the most popular illuminated manuscripts being produced. What made them so popular then, and why particularly in England?

MORRISON: One of the greatest conundrums remaining about the bestiary is why it became so popular in England. There certainly were French copies, especially in the second half of the thirteenth century, and then it became translated into French and became a very popular French text as well. But we just had a study day with all of the great scholars who have studied the bestiary, and we discussed why England, because that’s something that we still don’t really know.

One of the suggestions from a scholar there was that it may have been a particular outgrowth of a monastic movement in that time period, in specifically England, who were very interested in reaching out more to the sort of general public, rather than individual monks.

CUNO: Yeah. So why did they disappear around 1300?

MORRISON: I think there’s a variety of reasons to think of the decline of the popularity of the bestiary itself, one of which is the concurrent growth in the thirteenth century of encyclopedias and the sort of birth of natural history. And so at some point, the bestiary text probably seemed a little bit old-fashioned.

And in fact, in the natural history section of this exhibition, we talk about how the first encyclopedias used the bestiary fairly wholesale, and then they cut off the Christian context, and then they started rearranging the beasts in alphabetical order. So there was sort of gradual moment. But at the same time, in many ways, the bestiary has never disappeared. We talk a lot in this exhibition about how the imagery of the bestiary was one of the most important components of the visual language of the Middle Ages, all the way up through the Renaissance.

And in addition, as you know, we have a section on contemporary and modern artists working with bestiaries. And in fact, I think one of the sort of most charming things about the bestiary is that people actually know a lot about the bestiary, even if they’ve never heard the word. Because almost all the animal expressions we use, like a memory like an elephant, wily as a fox, monkey on my back, crying crocodile tears, those are all from the bestiary. So it does linger in the culture, nevertheless.

CUNO: Let’s go look at some.

Here in the second gallery, you’ve got a whole range of styles and illuminations of the bestiaries. So tell us about this one. This is Christ in majesty, Adam naming the animals. It’s English. It dates from about 1200.

MORRISON: This is one of my favorite bestiaries. This is a bestiary from the University of Aberdeen. As you mentioned, it was made around 1200, in England. And since that time, in the past 800 years, it has never left the United Kingdom before. So this is its very first vacation out of that area to Los Angeles. And so we’re incredibly honored to have it here.

Because as you can see, it is one of the most ambitious and beautiful manuscripts ever created, not just among bestiaries. If you go to Wikipedia and you look up illuminated manuscript, this is the image you see. So in many ways, it is sort of standing in for all illuminated manuscripts, because it is so glorious.

CUNO: Well, describe it to us. You’ve opened it to what I assume to be nearly the first two pages, if not the first two pages, with Christ enthroned on the left and the animals on the right.

MORRISON: Exactly. Bestiaries often begin with a series of creation images, because it was thought that God created these animals with these behaviors inherent in them at the beginning of time. So it makes sense to open with scenes of creation. So you have Christ in majesty, as you said, at left, with lots and lots of gold, brilliant colors. And he’s sort of presiding over the idea of creating the world.

And what you have at the right is actually Adam naming the animals. And all the animals are depicted in these sort of little compartments, as they come towards him. And the top ones that you see are the felines, the top of the food chain. And they’re the ones that eat everything else. And then below them, you have the wild animals that they eat, like the stags. In the next compartment down, you have domesticated animals, like cows and oxen. And then down at the bottom, you have all the smallest creatures, like cats and dogs and bunny rabbits and squirrels.

And so the animals are kind of presented in this hierarchy, which is exactly the way that most bestiaries are arranged. They’re arranged into categories. So they start with the land animals, then they go to the birds, then they go to the sea creatures, and then they go to the serpents. And so this kind of gives a little microcosm of what you’re going to find in the bestiary.

CUNO: Well, let’s look at another. Larisa, what’s your favorite in the exhibition?

GROLLEMOND: So this is a bestiary that was also made in England. It comes to us from the Bodleian libraries. And it is one of the most luxurious bestiaries. And what’s interesting about this one is that there is some evidence that it was made for a lay patron. And so this is one of the bestiaries that we think is kind of making the jump between monastic and secular audiences.

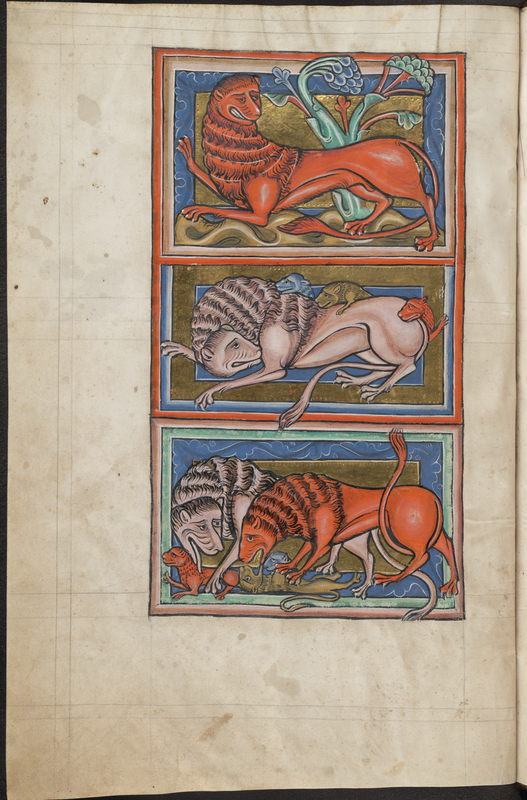

You can see from the style of the illumination, which is also quite brilliant—there’s a lot of gold leaf, really bright, saturated colors. And here, it’s open to the beginning of the bestiary, and you can see that really decorative B that starts the text, Bestiarum. And this page talks about the lion, who’s always first in the medieval bestiary, and who is identified as the king of beasts. And that’s an expression that we still use today, that we kind of understand about the lion being at the top of his food chain.

But in the bestiary, he’s identified as a type for Christ, as many of these animals are. And one of the most common images that you will see in medieval art, and something that makes the jump from manuscripts into other media, is lions breathing on their cubs.

And the bestiary says that lion cubs are actually born dead, and three days later, the father lion will come and breathe in their faces and bring them to life. And as Beth said, this is kind of an allegory for the idea that God put these behaviors into the animals at the beginning of time. And this is seen as a mirror of the death and resurrection of Christ three days later. And so this becomes a really, really popular symbol for all kinds of different art. Liturgical art, secular art, courtly art. And this is really the source text and where you see it for the first time.

CUNO: These lions have particular characteristics about them. They seem to be humorous, they seem to be frightening, they seem to be frightened, they seem to be vicious.

GROLLEMOND: Well, what’s wonderful about the bestiary is that the imagery really offers artists a lot of opportunities for personal expression. And so while you do see the similar iconography—so the way the images are composed—you’ll often see these really interesting artistic flourishes. And so the facial expressions of these lions in particular are just charming. And they really have a personality. The top lion, we always kind of liken to a used car salesman. He looks like he’s really drawing you in; kind of has this really playful grin.

And that’s really one of the features of bestiary illumination, is that the animals just really leap off the page.

CUNO: Beth?

MORRISON: And one of the things that’s, I think, amazing about all these manuscripts is that when you come into the gallery and you see them, I think a lot of people are surprised at the vibrant colors. But of course, these manuscripts were kept closed for most of their lives. They had no opportunity to fade, like other kinds of artworks we see.

CUNO: Now, in this first case, you’ve put seven different bestiaries. This one on the far right of it, depicts some elephants. Rather fantastic elephants, because I would assume it was made in England and they— elephants were not known by the artist who made these, depicted these elephants. But describe them for us.

MORRISON: So there’s quite a number of pictures of elephants throughout the exhibition. The idea of this enormous animal living in a far-off place like Africa, that was so strong that it could carry a castle on its back, filled with soldiers, which is the image you see at the top there. That was irresistible to the imagination of medieval viewers.

There was a very famous elephant that was given as a gift from the king of France to the king of England, in the second half of the thirteenth century. So we do know that one elephant at least, as a real elephant, made its way to England.

CUNO: Begs the question how the king of France got the elephant to begin with.

MORRISON: Yeah. I’m not sure of that part of the story. I think, you know, there was a lot of trade in the thirteen century…

CUNO: North Africa?

MORRISON: …with Africa. I mean, getting an elephant from Africa is a big deal, but that’s why it’s the king to the king, right?

So in this image, there’re sort of two halves to the image. The top is the elephant with a castle on its back, full of soldiers fighting. And at the bottom, you see another story associated with the elephant that’s told in the bestiary, which is that elephants have no knees. And so when they fall down, they’re kind of down for the count. And the story is that the elders of the elephant tribe come and try to lift him up and they can’t, and they’re very frustrated and they’re upset.

And then more elephants come and they can’t lift him up. And then the smallest elephant, who you can see there at the right, comes in, and he’s the only one who’s able to lift this enormous elephant up. And that was seen in the bestiary as a reflection of the fact that Christ, the humble, small Christ, was the one that was able to elevate and save all of humanity by himself.

CUNO: Larisa?

GROLLEMOND: So Jim, as you said, these kind of look like elephants. They’re elephants, in the broadest strokes. But one thing that I love about bestiary elephants is that the artist has always had a lot of fun with the physiognomy of the animals. So they are sort of big fat creatures, but they come in all sorts of colors. And they sort of have these ropey tails, but they can have kind of paw-like feet. And the ears are always something that the artist cannot quite get. So sometimes they have, you know, pricked ears, like a dog would—all different kinds of shapes. And often, their trunks are like trumpets. So they get wide at the end, which you can see here.

CUNO: So here’s a fantastic image. We just went from an elephant to now we’re at a whale. Tell us about this one.

MORRISON: So this is the manuscript that really kind of started it all. This is one of the Getty’s bestiaries. Back in 2007, I realized that we had two bestiaries in the collection. And then we acquired a third bestiary, the Northumberland bestiary. And at that point, I thought, you know, no one’s ever done an international loan exhibition on the bestiary. What a missed opportunity. Why don’t I take that opportunity? So that gave me the idea for the exhibition. So this is a Getty manuscript. And this is one of the most famous images in our collection, because it’s so amazingly ambitious, beautiful, colorful. It shows the whale, as you mentioned.

And the story in the bestiary, of the whale, is that it is so large that it can float on the surface of the ocean for days and weeks. And eventually, soil comes down and then seeds come down, and grass grows on its back, and sailors come along and they think it’s an island. And so they make camp on its back. And when they light their fire, which is actually depicted in the illumination, the whale feels it and he knows that there are sailors up there. And so he plunges them down to the depths of the ocean and drowns them. Not very nice.

But it’s seen as a metaphor for the idea that if you put your Christian faith on an unfirm foundation, the devil will take you down to the depths of hell. There’s actually quite a bit of Christ and the devil in the bestiary. Those are probably the two most popular characters.

But what I love about this illumination is that there are two sailors depicted still in the boat. And they’re looking at each other with this expression of pure horror, because it’s the exact moment when they’re like, uh-oh, not an island. And then there’s a third sailor who’s grasping onto the sides of the boat. And he’s grasping so hard that his arms have actually elongated.

And another reason that this is my favorite illumination in the collection is that this animal, in the bestiary’s referred to as a belua, which is a Latin word that simply means ferocious beast. And because I’m such a medieval geek and such a bestiary geek, I named my dog Belua, and she’s a big, fat, chocolate Labrador retriever, just like the whale is.

CUNO: Well treat her well.

MORRISON: Yes. And she’s much nicer than the devil.

CUNO: Yeah, okay. The next to that manuscript, the manuscript we were just talking about the whales, is one dedicated to sea creatures, with really extraordinary depictions of these fantastic creatures. What is the role of this one? Larisa?

GROLLEMOND: So we’re looking at a manuscript that has a depiction of two different sea creatures, one on each page of this opening. And one thing about the bestiary is that it is categorized. So it goes from the land animals to the birds to the sea creatures, and then serpents. And the categories are quite broad. So really all of the animals that live in the sea are considered sea creatures, even though it encompasses things that we now know as mammals.

So on the left, we actually think that that may be a walrus, but it’s called in the text, sea pig. It has these tusks and kind of a fin-like thing in the back and these really beautiful eyes. And this really, I think, gets at the idea of the medieval categorization of animals into these hierarchies, because he’s a pig-fish. And it’s thought that in the Middle Ages, that all of the animals that live on the land have a counterpart in the sea. So the idea of sea horses and sea pigs and all of these different things are something that you do see in the bestiary.

CUNO: Now, we’re in front of a book opened to two pages, both of which have dragons on them, fiery breathing dragons with long tails and sinuous bodies. Tell us about the role of the dragon in the story of the bestiary.

MORRISON: So the dragon is introduced at the beginning of the section on serpents, because just as the lion is the king of beasts, the dragon is the king of serpents. So each of the sort of subsections have a separate king. And this is the dragon. The dragon is known as the most powerful beast. And what I think is particularly amazing about this page, that’s really common in bestiaries, is you can see that the red dragon at the right sort of slices diagonally through the page. And you can see that his tail actually cuts through the text, so that there’s text on either side of his tail.

And this is a very unusual feature that you associate with bestiary manuscripts in particular, because there’s horns and wings and hooves and tails like this cutting through the text. And that required quite a bit of coordination between the illuminator and the scribe, which was very unusual in manuscript. In fact, usually the scribe came through and just did whatever he was going to do, left the spaces he was going to leave for the illuminator, and then went on his merry way.

But in the case of many of these bestiaries, the illuminator and the scribe had to work together because the illuminator had to say, “Oh, I’m going to put a tail through here. You need to leave this space.” So he probably drew out something for the scribe to write around. And what I think is exceptionally clever about this particular one is the place where the tail interrupts the text for the first time is the portion of the text that talks about the power of the tail of the dragon.

So they clearly were working incredibly closely together to give meaning to the interaction between text and image.

CUNO: Well, tell us about the text. What is the story here?

MORRISON: So the text talks about the dragon as king of serpents, because he is the most powerful. It talks all about his different powers. But the most sort of amazing power he has is in his tail. And his tail is so powerful that it can knock over the strongest animal on the face of the earth, which is the elephant. So the dragon sort of lurks on the paths that he knows that elephants take, and when the elephants come along, it wraps its tail around its feet and takes it off its feet. And as we know from previously, poor elephant can’t get up.

CUNO: Right, right. Now, I would’ve thought the fire-breathing dragon would’ve been the most frightening.

MORRISON: You know, it’s interesting. The bestiary doesn’t really talk about the fire-breathing dragon. It talks about these other aspects. And the fire breathing is something really that the artist adds in, probably because it was a popular idea that dragons breathed fire.

CUNO: So now you include in the exhibition objects other than manuscripts including tapestries, capitals, parts of a painted ceiling, aquamanilae—which are water vessels—ivory caskets, even board game pieces. How do these relate to bestiaries

MORRISON: So as we talked about, one of the things that’s interesting about bestiaries is that the iconography, or the elements and the way they’re composed on the page, is very stable throughout the entire history of the bestiary. So if you see the lions breathing on their cubs, they’re done in exactly the same way. The unicorn leaping into the virgin’s lap, she’s always on the left. The unicorn is coming from the right, the hunters come from the right. And so those images were really readily recognizable. And they spread. They kind of leapt off the pages into all these other objects.

And because these other objects, of course, have no text, they were expecting you to know these bestiary stories, which everyone did, because it formed this kind of visual language with which everyone was familiar.

CUNO: So we’re now moving into a section of the exhibition that looks to the broader context in which the bestiaries could be seen, in which they had a kind of resonance. And we’re standing in front of two long pieces of a painted ceiling, comprising five medallions each, within which there are animals and figures. Tell us about these, and tell us about the way this would’ve been seen in a structure.

MORRISON: So we really decided that we wanted to kind of surprise viewers in the exhibition. So you come out of this intense area of looking at bestiaries and you move into this next room, and all of a sudden you have enormous panels, tapestries, these large-format architectural features, that help give you a sense of how much this bestiary iconography could be found on all sorts of different things.

As you mentioned, these were ceiling panels. There’s very few painted medieval ceilings that survive. And the fact that the museum in Metz, France, was willing to send these thirteenth century panels to us was really a testament to the way that the Getty is seen sort of internationally. These have never been lent before. I can’t imagine that they’ll be lent again anytime soon. And here they are in Los Angeles, which is really extraordinary.

CUNO: Would they have been in a dining room? In other words, would you be sitting at a table with aquamanile around you and plates and ivory elements that would have the animals depicted on them? Then you’d look up and there would be tapestries around the walls, and above them there would be wall paintings like this? So there’s a whole universe of such references, in which you’d be a small part.

GROLLEMOND: We do think that these were originally part of a context in which there would’ve been objects of many different media. These were actually rediscovered in 1896. And we think that they were originally part of the cathedral chapter house in Metz. So a kind of quasi-religious space, but also a space in which the canons and the people who were associated with the cathedral would have spent time.

And these were rediscovered in the nineteenth century because there had actually been a false ceiling installed just under them. And so they were quite well preserved and almost the entire ceiling survives.

And these rondels have a number of different bestiary creatures. So we have the unicorn in the center, that we’re familiar with, and then a few other ones. So just to the right of the unicorn is the story of the wolf. And the bestiary talks about how the wolf likes to hunt sheep. And while it’s prowling around a sheepfold late at night, it actually steps on a stick and alerts the sheep to its presence. And the wolf gets so angry at himself that he bites his own leg. He bites the offending leg. And you can see that that’s what’s happening here. And this is a reference to the bestiary that would have been made without text, without other context, and people would have recognized this as a bestiary story.

And you can also look up to one of the top rondels, where you see kind of an upside-down bird. And we know that this is an ostrich by his cloven hooves and the fact that he has horseshoe in his mouth. And the bestiary talks about how the ostrich can digest anything, even iron. And so he’s often shown with a horseshoe in his beak.

But many of these other animals are not specifically bestiary stories, but they’re hybrids. They have kind of these monstrous features. Many have two heads or sort of curly tails. We have something that looks a little like a griffin up at the top, but instead of a lion body, he has kind of a snake-like tail.

One thing I think is really interesting about bestiary creatures when they appear outside of manuscripts is that not only would have people have been encouraged to identify the bestiary animals, but this provides a lot of opportunities for additional meditation. So you might wonder about how these other animals work together, what they signify. And this would’ve been a religious exercise for the people who would’ve seen these in the cathedral chapter house.

CUNO: Well, over here we have something that looks to be like ivory elements of a game, like a predecessor to chess of some kind. And what is this about and what role would it have played in the culture of the bestiary?

MORRISON: So you can see that we have multiple game pieces here. When I originally saw these pieces, I thought they’d actually be about the size of checkers. But as you can see, they’re quite a bit larger than that. And they’re each beautifully and deeply carved pieces of ivory. One of the things that’s interesting about them is, for instance, at the top, you can see one of them is represented as an elephant with soldiers on its back, in a castle. So again, it’s referencing imagery that you would have known from the bestiary.

Now, unfortunately, we don’t know how these pieces would’ve been used in a game. They’re probably draughts or [changes pronunciation] draughts pieces, depending on whether you’re American or English. And we don’t really know how they would’ve been deployed during a game, may have been related to the way that the animals were structured in the bestiary. So for instance, you might’ve had, you know, certain type of land animals versus the domestic animals or something like that.

But one of the other things that you’ll notice is a number of the animals—and we’ve grouped them here in the center, four—have little babies. So it may’ve been a sort of, you know, battle of the sexes. Maybe the female pieces against the male pieces. We don’t really know how they were used.

But these are on loan to us from the British Museum. And the curator there became very interested when we started talking about this, and so he’s doing some research into games. And I think that’s one of the things that’s wonderful about these exhibitions is it spurs institutions themselves to become interested in their own collections in ways they hadn’t thought of before.

CUNO: Well, this world of animals includes these fabulous aquamanilae, these bronze depictions of fantastic animals, in which water or wine would’ve been put, and from which water and wine would’ve been spouted.

MORRISON: Yeah, so aquamanilae were used in the Middle Ages for purified water. And we think that they were used at feasts; you might want to ritually wash the hands of your guests before the meal started. Or they were used in liturgical services, where the priest would want to wash his hands before mass or some other religious service. I think it’s particularly appropriate to find an aquamanile in the form of a unicorn, because as we mentioned, the unicorn’s horn was thought to have miraculous powers, including detecting poison in water.

CUNO: So now we’re in a part of the exhibition in which there are three aquamanilae, and they’re extraordinary, each different from the next, but all serving the same purpose, I assume.

GROLLEMOND: Yes. So we often see aquamanilae in animal shapes. And you can see here, this trio of aquamanilae is all different feline shapes. So we have two lions and a cheetah. And what’s really interesting about this grouping is they really represent the diversity of religious practice, and then geographical diversity as well.

So on the left, we have a lion aquamanilae that actually has a Hebrew inscription on his side. And so we think that this was actually used in Jewish services. And the inscription says, “Blessed be the king of the universe, who has instructed us to wash our hands.”

In the center, we have another aquamanilae, probably from Western Europe, and probably used for Christian services or, as Beth mentioned earlier, for feasts and ritual hand washing. And then on the right, we actually have a cheetah.

And you can see the incised stripes that he has kind of carved into him. And this aquamanilae is actually from Italy or Egypt, and was probably made in an Islamic context. And we think that Islamic courts made use of cheetahs as pets or as hunting companions. And what I think is really interesting about this grouping is that it shows the really wide diversity of animal symbols to be used in many different religions and across many different geographies.

CUNO: I think one of the most startling subjects which features the animals out of this bestiary world that we’ve been looking at and talking about, the female pelican, who is cutting herself with her beak, causing herself to bleed from her breast, to feed the young pelicans at her feet. And this one in particular, because the kind of next in which the pelicans are situated, waiting for the blood to come from the breast of the mother, is almost like a crown of thorns.

MORRISON: Exactly. This is a really unusual survival. We don’t have too many alter sculptures like this made of wood that have survived. And as you said, it’s the story of the pelican, which is a little bit of an odd one. I don’t think you associate that story with the pelican. But the idea is that the mother pelican is a good mother, but her children annoy her constantly, until she gets so fed up with them that she actually kills them. And she feels really bad about this. And she realizes the only way to bring them back to life is to cut open her own breast and pour her blood over her chicks. And of course, this is another metaphor for the crucifixion and Christ being willing to spill his blood to save mankind, his children.

One of the interesting things about this case, you can see that there’s four different pelican objects that are completely different in medium, but also in time period and place. And at the far right-hand side of the case, you actually have a beautiful object from Italy.

So we don’t know of any illuminated bestiaries from Italy. But we know that the stories made it down there, and one of the most popular was the pelican.

CUNO: Well, it’s featured, the pelican is featured, prominently in this tapestry just to the left over here, which is remarkable. And it looks like a 1920s German Bauhaus tapestry. Tell us about this.

GROLLEMOND: This tapestry comes to us from an abbey in Germany, Lüne Abbey. And we have a number of pieces that feature bestiary animals, and in particular pelicans, from this Abbey around 1500. And this is one of the objects in the show that we think was made by female artists, for the use of females in this convent kind of space. And what’s really striking about it is, as you say, the color. It’s so graphic and so sort of interesting in the way that it organizes the composition.

So you can see the familiar pelican mother, with her wings kind of outstretched behind here, but then this one single claw that she has, that kind of forms the basis of the composition. And then her three chicks, which all are reaching up. And they have these really dramatic-shaped eyes that kind of fall down their bodies. And they’re all waiting for the three drops of blood that have appeared on her breast to come down to them.

And although we don’t know the original purpose of this particular tapestry, we have another tapestry in the exhibition that was used as a pew cover. And so the nuns of Lüne Abbey seem to be extremely interested in this kind of imagery, and often we see them in these long pieces of tapestry. This one would’ve been part of an even longer piece of tapestry. And there is this colorful fringe that hangs off the bottom. So this could be used in a lot of different contexts.

CUNO: Beth?

MORRISON: As Larisa pointed out, there are three chicks and three drops of blood, which probably is a reference to the Trinity—God the Father, God the Son, and the Holy Ghost. And so when we were talking recently about how this tapestry could’ve been used, we were wondering whether this was a decorative sort of border that might’ve gone along the top of a cathedral or top of the church at Lüne, and may have been brought out on things like the Feast of the Trinity.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, this brings us to the end of the kind of medieval portion of the exhibition, because then you leap into the sixteenth century over here, with a couple of paintings.

One a German painting of a hare, or a rabbit, set within a wooded landscape. By Hans Hoffman, from the sixteenth century. And then another painting to the right, by Jan Brueghel the Elder, called The Entry of the Animals into Noah’s Ark. What is the context? How do these relate, then, to the predecessor bestiaries?

GROLLEMOND: So these two paintings appear in a section of the exhibition that explores the bestiary as foundational for the development of natural history and the nascent fields of zoology. And as we move into the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and even the seventeenth century, we have the same idea of observing animals in their natural spaces and kind of getting to know animals in a different way.

These two paintings, obviously, take the level of observation to new heights and new details. And something that people always say about the Hare in the Forest, the Hoffmann painting, is that it’s larger than they expected. Because it’s so carefully observed, it has such naturalistic detail. And so we see these kinds of paintings as the kind of natural progression of bestiary illumination, into a world that is more concerned with collecting natural specimens, observing them very closely, and cataloging them in more scientific ways.

MORRISON: Both of these paintings are actually from the Getty’s collection. But one of the things that I love about these two paintings is they sort of show the two sides of how the bestiary develops. One, as Larisa was saying, into forming something like a hare into basically, a monumental painting and showing the diversity, in excruciating detail almost, of the natural world; and then this image by Jan Brueghel the Elder, which shows Noah’s Ark. And so it’s still putting the animals within a religious narrative. These are all the animals of the world, just the way the bestiary was all the animals of the world.

But here, you’ll notice there’s no unicorn, but there’s things like guinea pigs. And guinea pigs had just been brought over from the New World, as a new sort of scientific specimen. And so that’s what’s being incorporated into this ongoing legacy of the bestiary.

In fact, the animals are arranged into their categories, just the same way they had been in the bestiary. So all of the land animals are sort of grouped together, all the small animals appear in the front center, and then all the birds are grouped together. So you’re seeing them in these categories that were inherited from a very, very long tradition.

CUNO: Now, we leap, in the final gallery in the exhibition, into the twentieth century and the twenty-first century. And there’s a range of objects comprising the end of the exhibition, including modern bestiaries, the theme revisited. But there also are just wondrous animals. Tell us about these.

MORRISON: As we wanted to start the exhibition with a bang, and that’s why we chose the unicorn, we wanted to end the exhibition with a bang. And we really wanted to show that the bestiary is not some dusty, old, dead tradition, but in fact, continues to inspire artists today. And so we gathered together a group of books, which as you said, are actually called bestiaries.

In the nineteenth century, the bestiary had a kind of revival, and so artists began working with it. But we have artist books that go all the way up to 2017. And nowadays, we use the word bestiary to refer to any sort of collection or series of animal images, often related to text.

But we also wanted to include contemporary works of art that spoke to how three-dimensional artists are dealing with the bestiary and with animal imagery. This was a part of the exhibition that I really asked Larisa to take over and curate, and so I’m going to turn it over to her to talk about some of the individual works of art.

GROLLEMOND: Sure. So the quintet of contemporary artists that we’ve put together are all working with the idea of the human and animal worlds and the interaction between them, and in many cases, using animals as allegories for human sufferings and themes. And they’re, to varying degrees, familiar with the medieval bestiary and using the medieval bestiary as a direct inspiration; but they’re all interested in the idea of mythologies and animals as vehicles for telling stories.

CUNO: So let’s take a look at this sculpture, I guess you’d have to call it, of an impala, which is actually the animal itself, that has been preserved and stuffed and into which there is integrated a very human-like face. Describe it for us.

GROLLEMOND: This is a tough one to describe, I think. This is one that you kind of have to experience. So we hope that you’ll be able to get to Los Angeles and see this piece in person. As you said, it’s a taxidermied hide of an impala, kind of antelope-like animal, that the artist has actually combined with a sculpted human face. And this is characteristic of this particular artist’s work. Her name is Kate Clark; she’s working out of Brooklyn. And she’s really interested in the fusion of human and animal. In this case, quite literally.

So she uses human models, on which she bases the specific features of the faces. And each of her works combines different species of animals with different faces.

CUNO: It looks so natural there that it seems so convincing that this animal would have this face.

GROLLEMOND: Yeah. She really incorporates the face into the hide by using bits of the hide to form a kind of skin of the face. But then the face is also heightened with these silver pins that really give it a sense of lifelike presence. And this piece is particular in Kate’s work, because it was commissioned by the African-American poet Claudia Rankine, for use in one of her books. And the poet felt that the piece actually was too beautiful to use in her book, so ended up choosing another of Kate’s works. But that was the original commissioning of the work.

And she calls it Pray, P-R-A-Y. And the wordplay of the title references the poet’s feelings about growing up as a young African-American girl and the struggles she faced in doing so, and the idea that she needed to take refuge in her faith, while at the same time feeling pursued.

CUNO: We’re coming over here to the final object in the exhibition, and it is appropriately, as we began with the unicorn, it is a scull of a unicorn, so to speak.

GROLLEMOND: Yes.

CUNO: Describe it for us.

GROLLEMOND: So this is a work by the artist Damien Hirst. And it is a unicorn skull. It’s a horse skull that actually has an attached horn. Or is it? It might be a unicorn skull. But it’s gilded silver, and so it has this really amazing presence, in terms of color and shine. Although it dates from 2010, I was originally exhibited in the 2017 installation in Venice. It was called Treasures From the Wreck of the Unbelievable.

And the sort of conceit of this installation was that divers had recently discovered a shipwreck of the ship The Unbelievable. And it was packed full of all of these different treasures, many with mythological connotations. So there’s Medusas and other things. But this unicorn skull is one of a few that were supposedly found amongst the ruins of the shipwreck.

And I think it’s interesting because it asks the viewer to consider the limits of their belief, and the kind of fine line between fantasy and fiction. We sort of talked about the rise of science and naturalistic cataloging, and this kind of challenges that. It presents the physical remains of a creature that we know that doesn’t exist, and kind of asks us to consider, to unicorns really exist?

CUNO: Yeah, well, it’s a very beautiful exhibition. Congratulations. It brings out the magic of the culture within which these objects had a role to play.

MORRISON: That’s what we were thinking this final room does, in a way, is that when you walk in, you’re like, oh, look at that creepy impala thing. And you know, is that really a unicorn skull? And we think it really, in a way, replicates the experience that medieval viewers had in looking at the bestiary for the first time, because there were all these fantastic and wonderful creatures that really induce thought and encourage conversation. And we’re really hoping that’s what this exhibition does.

CUNO: Yeah. Well, congratulations and thank you so much for letting us bring you onto the podcast.

MORRISON: Thank you so much for your time, Jim.

GROLLEMOND: Thank you so much.

CUNO: Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World is on view at the Getty Center through August 8, 2019.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

ELIZABETH MORRISON: Lions and unicorns and dogs and cows and manticores and phoenix were all evid...

Music Credits

“The Dharma at Big Sur – Sri Moonshine and A New Day.” Music written by John Adams and licensed with permission from Hendon Music. (P) 2006 Nonesuch Records, Inc., Produced Under License From Nonesuch Records, Inc. ISRC: USNO10600825 & USNO10600824

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.