This is the first in a series of conservator’s reflections on artworks in Pacific Standard Time.

Stephan van Huene is recognized for his acoustical sculptures—which he called “machines”—that combine movement and sound. With the flip of a switch, the sculpture becomes a show.

His 1967 machine Tap Dancer put on a performance every half hour in Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture, 1950–1970.

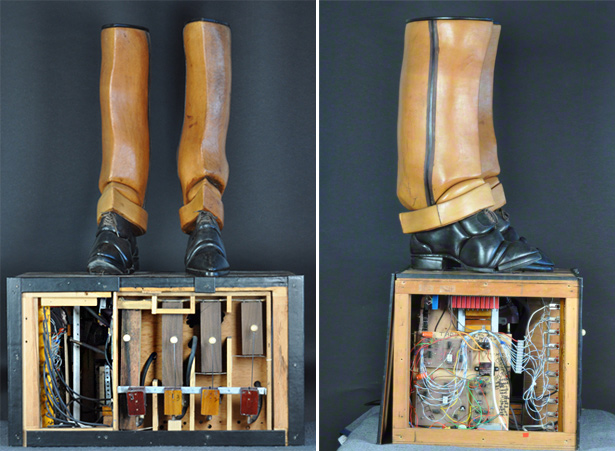

Tap Dancer (front and side views, with base panels removed), Stephan Von Huene (American, 1932–2000), 1967. Wood, metal, and mechanical components, 120 x 90 x 75 cm. Collection of Nancy Reddin Kienholz. Artwork © Petra von Huene, Hamburg

Beautifully crafted wood and leather boots stand on a simple base with four removable sides that conceal a complex network of circuit boards, wiring, and mechanical constructions. The photo above shows a rare view of the Tap Dancer in the sculpture and decorative arts conservation laboratory at the J. Paul Getty Museum with its sides removed. The movement runs for three minutes and then freezes. If your first glance is during the static pause, the start of the tapping and the accompanying abstract sound composition is a pleasing surprise.

John Gaughan, who restored the sculpture prior to the exhibition, found the initial startup to be magical, and discussed Tap Dancer with us in a video here.

Much like the electro-pneumatic action that controls pipe organs, first used in the 19th century, Tap Dancer integrates circuit boards that control the “wind” of vacuum air pressure through valves and piping linked to recycled musical components. The percussive sound comes from wooden-headed mallets striking four wooden blocks from a xylophone—an interesting choice as some of the first Western uses of the instrument was for theatrical acts of Vaudeville.

Detail of the bellows, mallets, and idiophone of Tap Dancer, with piping and wiring on the left.

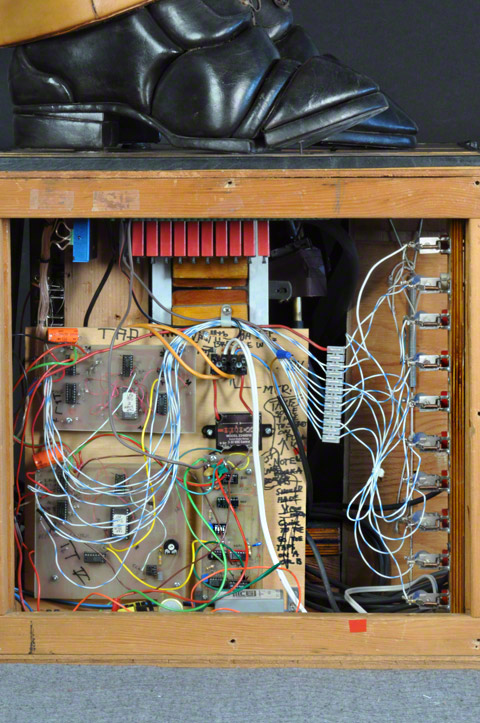

Tap tap, move move: Detail of the piping and wiring of Tap Dancer

Von Huenes machine-sculptures have many conservation issues, particularly when they are on display and plugged in for action. The condition of the wiring and circuitry is critical to allow the boots to perform their composition, which is intended to be random by way of an EPROM-circuit with a devised connection to a E050 timing circuit. The EPROM is a memory chip that contains the data for the timing-circuit that permits the flow of electricity to power the program at regular intervals.

When the Tap Dancer arrived at the Getty, the electrical component was not functioning. It had suffered wiring problems in the past. In 2002 the connection to the pins was resoldered for an exhibition at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. Also, the restorer smartly backed up the EPROM data for future conservation. Data stored in an EPROM circuit is not expected to remain for longer than a decade, so without backup, the original musical composition could be lost.

In 2010, prior to Tap Dancer‘s exhibition at the Getty, John Gaughan and Associates restored the circuit boards and made repairs, leaving the original components intact. At that time, we discussed with John our additional concerns about the mechanical stability of the sculpture and whether the handmade assemblage of components could withstand the rigors of a six-month exhibition. In fact, the artist designed the sculpture so its three-minute show could be activated two ways: automatically by the original timing circuit that triggered tapping every 15, 20, or 25 minutes, or manually via an attached foot pedal. In an attempt to control the amount of movement over a six-month period, we decided to use a timing circuit option, but John installed a new one that would start the tapping every 30 minutes.

Right side of Tap Dancer‘s base showing the original circuit boards and wiring. The red box on the top is a Gilderfluke & Co. PB-DMX/32 relay controller added by John Gaughan during the 2011 restoration.

Unfortunately, the construction suffered a lot of strain during the exhibition at the Getty. Only weeks before the end of the exhibition, Tap Dancer lost the tap in his left boot. And soon after that, the same boot stopped moving from side to side. It had to be removed from the exhibition early, and we are now working again with John to restore the sculpture.

Detail of the metal plate in Tap Dancer that broke due to mechanical strain.

This time the issue is mechanical rather than electrical. A metal plate that shuttles connections from the bottom of the heel to the air mechanisms has broken in half due to strain in the metal. Also, one of the mallets has distorted, so that it no longer hits the top of the idiophone when struck. The plate will have to be replaced and the mallet readjusted to get the Tap Dancer operational again.

Why not just repair the plate? The break occurred along an axis of strain, and no adhesive would be strong enough to withstand future operation. Welding the plate would be invasive and result in distortion. It is critical that the shape remain the same in order for the adjoining mechanisms to align correctly. So John will remove the entire plate and replace it with a replica—though the original plate will stay with the object. Then the mallet will be repositioned so it can lift the toe again.

By default, the Tap Dancer has been forced to take a rest, and could not accompany the exhibition to its second venue in Berlin. Our experience with the Tap Dancer has informed us about the conservation issues for his “machines,” and revealed that, with the desire to exhibit the works as intended, the endurance of their structures are inevitably at risk—a matter of concern that will continue to resonate for conservators and curators in the future.

Detail of Tap Dancer‘s boots. Soon they will tap again.

Fascinating insight into the ‘backstage’ of this piece, which I happened to come across when it was exhibited in 2010. The electronics and mechanics obviously come from another age, and it is interesting to think of restoring them in the spirit of their times rather than upgrading them to contemporary technology. If you haven’t thought of it already, it would be nice to display the video you linked to on a screen beside the Tap Dancer when it is next exhibited.