Car Hood, Judy Chicago, 1964. Sprayed acrylic lacquer on car hood, 42 15/16 x 49 3/16 x 4 5/16 in. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Acquired 2007 with means from The Second Museum of our Wishes. Artwork © 2011 Judy Chicago / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © Donald Woodman

In 1964 Judy Chicago created this wall-mounted sculpture, Car Hood, from a steel car hood and traditional automotive paint. The work was on loan to the Getty for Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture 1950–1970, and my colleagues and I had the opportunity to examine it before it went on view, and to stabilize it for further travel afterwards.

The sculpture is owned by the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and the risks of transporting it over such a long distance became clear when, upon unpacking the object, we observed flecks of paint in the bottom of its crate. Though the structural problems with Car Hood were pre-existing, the transport aggravated the condition. The backplate was lifting across the bottom and on the left side, causing the paint to crack and spall. It was the courier’s judgment that both cracks had opened further during the shipment, causing more paint to be lost.

The back (wall) side of Car Hood. Photo: Raina Chao

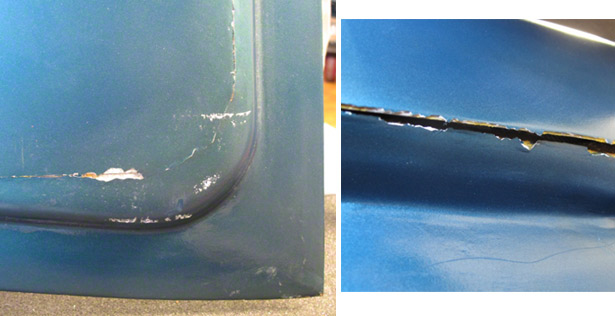

Two details of the cracking on the back of Car Hood. Photos: Julie Wolfe

A car hood isn’t a typical material for a sculpture, but Chicago was one of several California artists in the 1960’s who adopted techniques and materials from L.A.’s car culture. She attended auto-body school and learned the skills for spraying the unfriendly paint. Her talent is clearly apparent in her paint application on Car Hood. The artist created the abstract painting on the front using traditional paint layers and careful taping.

Car Hood was originally thought to be made from a Chevrolet Corvair hood from the early 1960’s, but the artist’s husband, Donald Woodman, recently explained that the exact type of car is actually unknown. Our X-rays of the object revealed a construction that does, in fact, differ from that of a ’60s Corvair hood, though we don’t have enough information to pinpoint the make and model.

An early 1960’s Corvair car hood. Courtesy of Katarina Havemark

Chicago started two other car hood paintings at the same time as the Moderna Museet’s Car Hood, which were only recently revisited by the artist and completed.

We spoke with Chicago at the Getty Center about the piece in December 2011. She didn’t remember putting a plate on the back—it was likely put on by someone at the auto-body shop she attended (presumably by welding). She then filled the edges with Bondo putty herself and sanded them. She said Bondo came in a lot of different densities and there were numerous car fillers available, so it’s likely several different filler products were used.

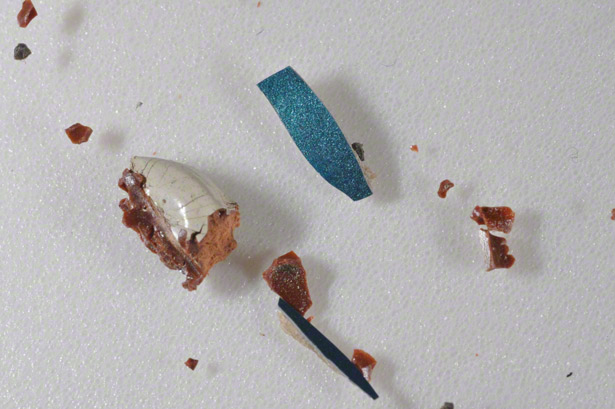

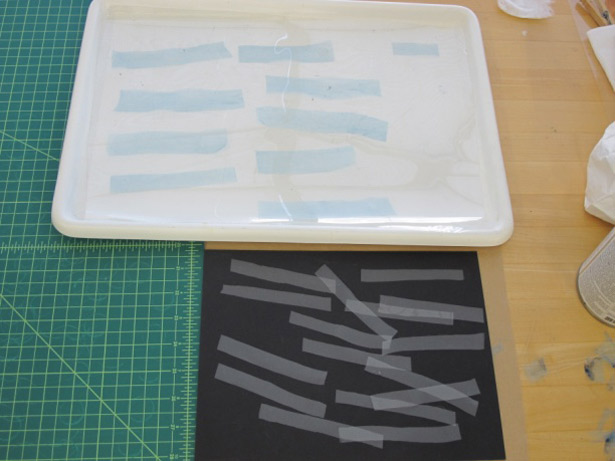

Paint fragments from the bottom of the crate used for analysis

Science helped us better understood the exact materials used in making the sculpture. Colleagues at the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) analyzed paint fragments from the crate and found that the red-brown fill included a natural resin, such as a colophony, along with calcium carbonate and possibly some polyester. After filling, Chicago applied a primer (which we saw in magnified cross-section images) based on a PVA (polyvinyl acetate) along with calcium carbonate. Then she sprayed on an automotive paint—the manufacturer of which she could not remember—and finished with a clearcoat.

Our GCI Science colleagues said that they have often identified nitrocellulose in automotive lacquers used by Los Angeles artists in the 1960’s, but the one on the back of Car Hood is different. The sample analyzed was a complex copolymer containing acrylonitrile, acrylic, styrene, and polyester.

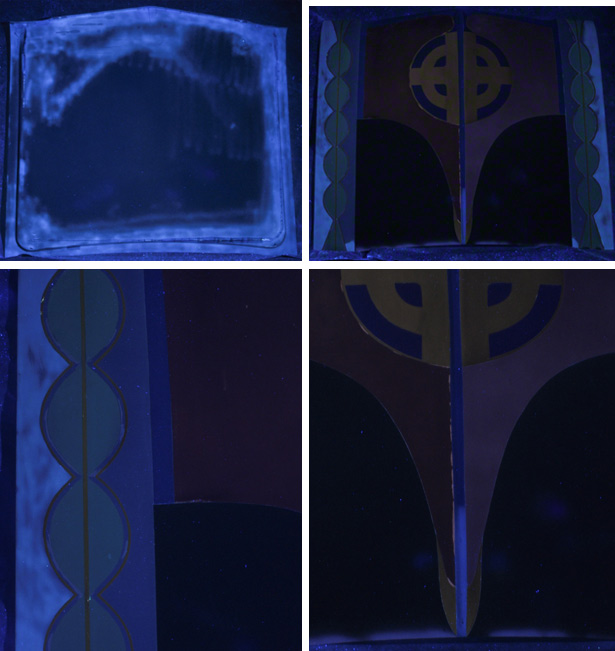

Chicago recalled that it was toxic paint, and she had to use acetone to clean out her spray gun. She described how she intentionally applied thick layers of clearcoat so she could buff and polish the surface without removing paint—although examination under UV light revealed limited clearcoat application, seen fluorescing as the whitish film in the photos below.

The back of the hood is loosely sprayed with clearcoat primarily around the edges, and on the front it only seems to exist in the side banding element. Our UV examination of the front also showed that the orange paint used for the central round-cross shape is different on the right and left sides, although the two sides appear quite similar in natural light. We made the same observation about the red sections surrounding the circle.

Four images of Car Hood under ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Clockwise from top left: back, overall; front, overall; front, detail of bottom edge; and front, detail of left edge

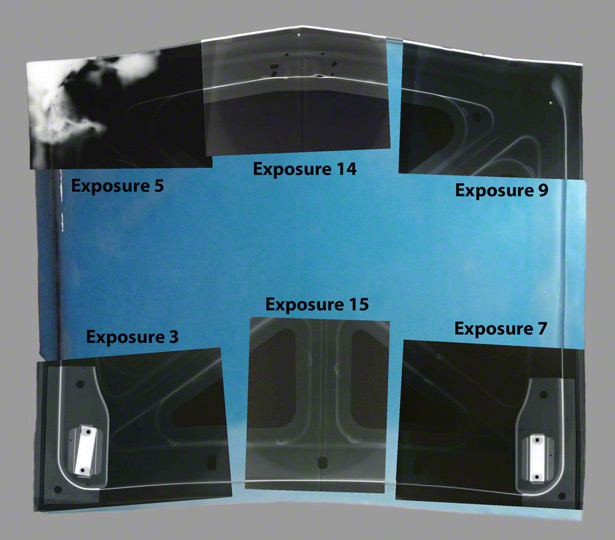

We also X-rayed the sculpture in six different areas around the perimeter of the hood. Unfortunately, it was difficult to distinguish between the original hood construction and the backplate added by the artist. There are several holes where hardware would have been removed, such as the box containing the lock to pop the hood open and the areas where hinges would have been attached for connection to the body of the car. There are also circular dense areas that could be welds, though they more closely resemble adhesive. It’s not clear if those rounds are between the hood and the backplate Chicago added, or between the original two components of the hood itself. There are also two or three screws within the sculpture, likely mechanical attachments for the backplate and hood.

Diagram of six X-radiographs over a photo of the reverse side of Car Hood

Based on the X-ray examination, we determined that the backplate was structurally stable, and that the edges of the backplate had lifted from the vibration during travel. The gauge of the plate was thin enough to allow the metal to warp, releasing tension at the edges.

There wasn’t time for a conservation treatment of Car Hood while it was at the Getty, but it was clear that the backplate needed to be reinforced prior to the sculpture’s being shipped again. The Moderna Museet asked us to stabilize Car Hood after Crosscurrents ended, and, in close consultation with our Swedish counterparts, we decided to apply a temporary facing over the splitting edges to prevent more paint from being lost during the trip back to Europe. Once the object returned to Stockholm, conservators could easily remove this protective layer with cotton swabs dipped in water before embarking on a longer-term treatment plan.

Before gluing on the facing, we tested the solubility of the blue paint on the backplate so we could choose an appropriate adhesive. Fortunately water was not harmful, so we chose a water-based adhesive, Aquazol 500 in deionized water. For the facing itself, we chose a fine fabric made from polyester multi-filament yarn called Stabiltex. We cut strips out of the fabric and toned them blue using paint to improve the appearance of the linings, which was partially visible from the side when the sculpture was installed on the wall.

Detail of Stabiltex strips used to create the facing for Car Hood

Toned Stabiltex linings applied to the cracks on Car Hood

Car Hood was shipped to Berlin in February for the exhibition’s second venue, and it was a relief to get the final report that the sculpture made the trip without any further paint loss.

It’s amazing to see that the achievements of women in fields traditionally male, which Chicago’s car hood and her practice at large so elegantly advocated, have expanded to the degree that the conservation of her powerful work of art is now being undertaken by three women – something I doubt would have been possible in the 1960s. Thanks to the women of Chicago’s generation for fighting, and bravo to these conservators who continue to prove what past generations of feminists knew women were capable of!

I think it could be a 1964 Buick Skylark hood, if that’s any help, conservation-wise.

‘Flight Hood’ looks 1964 Mustang. ‘Birth Hood’ and ‘Bigamy Hood’ are the often-mentioned 1965 Chevrolet Corvair. (A banal ‘man comment’, I know. Irony not lost on me.)

The Corvair hood shown here is from late 1960’s. Look at one from before 1964 and you will see that the x-rays confirm the Corvair hood.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=images&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwiYtsuRlLXXAhWRGOwKHULeAJoQjRwIBw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.corvair.org%2Fchapters%2Fnjace%2Fcorvair50th.html&psig=AOvVaw14eaM85PnFkWYp3MCirD64&ust=1510442637687809