In 1966, at the age of forty-one, Sidney Felsen moved from the world of accounting to that of art, founding the artists’ workshop and fine-art print publisher Gemini GEL in Los Angeles. With Gemini GEL, Sidney quickly got to work with some of the biggest artists of the twentieth century: Man Ray, Josef Albers, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg, to name a few. And Gemini GEL continues its work with new generations of artists, including Julie Mehretu, Tacita Dean, and David Hammons.

In this episode, Felsen talks about how Gemini GEL got started and grew into the organization it is today, sharing stories about the artists he’s worked with along the way.

More to explore:

Sidney B. Felsen Photography Archive

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

SIDNEY FELSEN: You can’t take a creative organization, creative endeavor, and tell them they have so many hours to do something or so many dollars to do something. You would absolutely thwart the creative spirit. So our business plan was there was no plan.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Sidney Felsen, co-founder of the renowned contemporary print workshop, Gemini G.E.L.

In 1966, college friends Sidney Felsen and Stanley Grinstein, with master printer Ken Tyler, opened the artists’ workshop and fine-art print publisher, Gemini G.E.L. Over the next fifty years, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, and Richard Serra would make some of their most beautiful and ambitious lithographs, screenprints, and mixed media prints at Gemini, just as today Julie Mehretu, Tacita Dean, Ann Hamilton, and David Hammons are making theirs. Sidney Felsen photographed these artists at work at Gemini. The Getty Research Institute recently received this archive of photographs as a gift from photographer and long-time friend of Sidney’s, Jack Shear, on the occasion of Sidney’s ninety-fifth birthday.

I recently sat down with Sidney to discuss the long and glorious history of Gemini G.E.L.

Thanks so much, Sidney for joining me on this podcast. Let’s start at the beginning, 1966, the year that you and your friend and business partner Stanley Grinstein founded the print publishing studio Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, on Melrose Avenue. How old were you then?

FELSEN: Forty-one.

CUNO: What happened before then? What brought you to the to the decision to start a business, as you did, at age forty-one?

FELSEN: Well, let’s see. To build it up from the beginning, all through my school education, I studied or major accounting. I went to Fairfax High School and USC. You know, in in that era of time, there was always an elective, I think they called it. You could take music or art. And I always took music, because I was probably afraid of art. I didn’t know anything about it. It was a different world.

And so I graduated college. I had zero interest in art. And then probably about two years after college, I did start to become interested in art. And it was the age of the moon and sixpence and lust for a life. So I decided I’d read about art. So that was by my introduction.

And then there was a gallery on La Cienega called Landau Gallery. It was run by Felix Landau. And I started going to exhibitions there, and I decided that I wanted to paint. You know, I didn’t think of myself as a professional painter; I just painted for fun. And so I took some private lessons and then I started a period of at least twenty-five or maybe thirty years, taking classes.

CUNO: Were you an accountant this whole time?

FELSEN: Yeah. When I graduated college, I worked for a small accounting firm and then a national firm. In order to become a CPA, you have to work two years for another CPA firm, and then you’d take these tests and all. So I became a CPA. And then I had my own office for several years. And so, say between 1950 and 1966, my whole means of ear— of a living was working in accounting.

But I became more and more seriously involved in art, as far as time. I won’t go into[?] probably Chouinard, which became a California Institute of the Arts. I went there for probably eight or nine years, maybe three nights a week and weekends. I ended up fairly quickly getting interested in ceramics, and wheel throwing, porcelains. And then the next sequence, as far as school, was Otis. And I went to Otis for probably seven or eight or nine years, at nighttime. And my teachers at Chouinard were Vivika and Otto Heino, H-E-I-N-O. And then at Otis, Peter Voulkos was teaching. Vivika was this very demonstrative woman, and she said, “You mustn’t go there. You mustn’t go there. That man is terrible. He’s breaking all the rules.”

CUNO: That was Voulkos she was talking about.

FELSEN: Voulkos, yeah. And you know, and in Peter’s class was Kenny Price and Billy Al Bengston, amongst many other ceramists. And you know, when somebody tells you you mustn’t go, you’ve got to go. So we all sneaked out around, went to— went there a couple times, just to see what the classes were like and so— But by the time I got to Otis, Peter had gone to teaching at Cal at Berkeley, and Henry Takemoto was teaching at Otis. So he became my teacher.

And so really, you know, like my life was very much filled with involvements in art. I mean, you know, became aware of— My classmates were pals, I [had] friendships with teachers, going to openings, you know, every Monday night on La Cienega had art walks, and I’d go to that. I mean, I spent a lot of time in the art world.

And so I was interested in everything. I never had any idea that I was a professional artist or I wanted to be one; I enjoyed what I was doing, I had a lot of fun, and I produced a lot of ceramics. Most of the things, by the time I really got into it and realized what I liked, was ceramics. And so I liked what I was doing.

CUNO: So where was Stanley Grinstein at this time, your partner in the development of Gemini?

FELSEN: Well, At USC at that time, you needed 124 units to graduate. And Stanley had 175 units and couldn’t graduate because he didn’t want to have any major. He just wanted to take what you want to take. And so there was a bunch of us in a fraternity, and we left and graduated in June 1950. And Stanley left, but didn’t graduate. And so his father had a business. Was material handling, which means forklift trucks or much bigger units than that. And then, you know, he met Elyse two years after graduation, after my graduation. And they got married.

And they became very interested in contemporary art. And they started the Contemporary Arts Council at LACMA, and Stanley was the president. They were seriously involved in collecting contemporary art.

CUNO: So what got you to start Gemini? What was the spark that did it?

FELSEN: Okay, so what happened was in my accounting clientele, I had art galleries as clients. And there was one that was importing prints from Europe. And you know, the usual in those days was Chagall, Miró, Picasso, Marino Marini or Zao Wou-Ki[?]. And I liked them and I was buying them. And so I was interested in prints. And incidentally, in all my years in these art schools, I never took printing. And so I was sort of fascinated by what was going on in this whole print world, as far as the importing into the United States.

And I liked that I liked the object itself. And so I don’t know, just one of these days, I said— one of those days, I said to Stanley, “You know, there’s these workshops in Europe. And it’d be interesting to have one in Los Angeles. We’d get to know the artists and we’d build collections for ourselves.” And his words were something like, “I don’t know anything about it, but if you want to do it, I’ll do it with you.”

And so in order to have a print studio, a print publishing house, you need a printer. And so Ken Tyler— He was an artist. He got interested in printing. He went to Tamarind. Tamarind was a…

CUNO: June Wayne.

FELSEN: …teaching institution on Tamarind Avenue in Hollywood. And June Wayne was the force, and the financing was done by the Ford Foundation.

CUNO: Right.

FELSEN: It was started 1960. They gave a five-year grant. And so Tyler became the technical director of Tamarind, and then left to start Gemini Ltd. And it was a for-hire workshop. You were an artist, you wanted to make prints, you’d come to Tyler, you do your work in the studio, and he prints it for you and charges your fee.

The things is that you’ve got to shift your mind. There was no art market in those— I mean, the prices you could buy things for were embarrassing, if you think about it compared to today.

So the word was out that Ken was trying to get UCLA to take over his studio as a teaching institution. And he was working at it pretty seriously, and it wasn’t happening. And so every year, the Grinsteins had a Christmas party. And so in 1965, we invited Tyler to come to the party. And so Stanley and I sat with him and talked with him all night about possibilities—what we wanted was to be a publishing house.

In other words, you invite artists to come into your studio. You know, it’s a collaborative event. So the artist contributes all the art, the artwork itself, and we’re the collaborator. And we have expertise in, say, in our printers there. And so they work hand-in-hand. The artist knows what they want to accomplish, but they don’t understand the process itself. So as a publisher, you own the work. You pay all expenses. Everything—travel, living, production, and distribution and warehousing and everything. And the artist provides the art itself, the imagery itself. And then the artist gets a royalty, as their work is sold.

CUNO: Was this standard practice or is this something that you made up or—?

FELSEN: No, no, no, no. It was standard, but there’s a lot of other standards.

M y awareness of the whole print publishing world was in Europe, so— We had no business model at that time.

CUNO: But like, Tatyana Grosman and ULAE, was that the similar situation?

FELSEN: At the time Gemini started, I had no awareness of Tanya Grosman’s ULAE or Kathan Brown’s Crown Point Press. But ULAE was very similar.

CUNO: Yeah.

FELSEN: Yeah, and Crown Point Press, up in San Francisco.

Look, there are publishers who do not have a printing facility. They farm it out to somebody like Tyler was in the beginning. It was just a for-hire shop. But we’ve always— From day one, we wanted to have our own printing studio, and at the same time be a publisher. So anyway, so Tyler accepted very quickly, and so we went about deciding who to invite.

CUNO: Which artist to invite?

FELSEN: Who, yeah.

CUNO: Yeah.

FELSEN: In the very beginning, we were chasing all the old timers: Hans Hofmann, Mark Rothko—

CUNO: Josef Albers?

FELSEN: Well, Albers was, yes. And what happened was Albert said yes, and he had been at Tamarind, working with Tyler. And so there was a relationship. And so Ken asked Tyler to work with us, and he immediately agreed that he would be the one that would, in a sense, open the shop, you might say. So that happened. And Josef did a series called White Line Squares.

So let’s see. Well also in the early days, the Los Angeles County Museum had a retrospective for Man Ray. And they asked Stanley and Elise if Man Ray could stay at their house. So we had a captive audience. But seriously, we were too timid to ask Man Ray to work with— We felt like we didn’t know—You know, Tyler was experienced, but Stanley and I had no awareness of what it would be like to have a print studio. We continued our own lives and earning a living, but we’d go there almost every night or on weekends.

So anyway, so we didn’t ask Man Ray. And then one day he said to us something about— He knew we had this shop and he said, “Well, what if I made some prints there?” So we said yes. So he did. One lithograph on paper. Two lithographs—they were screen printed, I think, onto Plexiglas. So he did three editions.

But however, you know, if you want to speak in the terms of in the beginning, in the first four or five years, it was amazing, you know. It was Albers, then Man Ray, and then Bob Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Claes Oldenburg, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Ed Ruscha, Ken Price.

CUNO: How difficult was it to attract the New York artists to Los Angeles to work?

FELSEN: Well a combination of, I think, the idea of coming to California.

CUNO: Especially in the wintertime?

FELSEN: Palm trees, sunshine, ocean, skiing. And if you looked at the calendar of who arrived when, all the East Coast artists came out in January and February, for some unknown reason.

Tyler did more of the actual going to talk to the ar— I went with him several times, but you’d had to give him credit for being more the salesperson of the thing

CUNO: With the migration of New York artists to Los Angeles, was any sense of competition among Los Angeles artists?

FELSEN: You know, as time went on, you’d have to define what’s a Los Angeles artist, because in those days, Bruce Nauman lived here when he when he worked with us, and Vija Celmins lived here when she worked with us. Ken Price, David Hockney. But most of the artists that worked with us were from outside of Los Angeles.

CUNO: There’s a great photograph you took of Frank Stella, Richard Serra, maybe Ken Price, playing basketball.

FELSEN: I think this would be 1971. We, the three of us owners, felt that Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, and Keith Sonnier were the three most interesting of the younger artists in the scene. And we invited the three of them, and they all came to work with us.

CUNO: It’s a little surprising because Keith Sonnier is a light artist.

FELSEN: Yeah.

CUNO: And to transfer that kind of interest in that kind of technique and talent into lithography or into printmaking isn’t a natural transition, I shouldn’t think.

FELSEN: Well, for one thing, he got us into making handmade paper, and the paper becoming the object itself. I mean, paper, you know, as big as this desk or bigger. You know, again, it was a different time. You know, when we started, prints were twenty-two by thirty inches. That was the standard and that was pretty much what printmaking was.

But you know, it didn’t take long for this whole era, whether it was Tanya’s or Gemini, the two to most likely, would reach out and try to— You know, like Bob Rauschenberg, in 1967, made what was believed to be the largest hand-printed lithograph. It was called Booster. It was primarily an X-ray of his body.

CUNO: So it was life-size?

FELSEN: Well, yeah, it was six feet tall.

CUNO: Yeah.

FELSEN: Bob wanted one X-ray plate that would be six feet. And we were quickly told by Eastman Kodak, “All plates are one foot.” So the Eastman had a machine in Rochester that had six-foot plates. It was the only one in the country. And Bob didn’t want to travel, so it was six one-foot plates.

CUNO: But you had the reputation for being a kind of artist print publisher. You go to lengths to follow the interests of the artist, beyond but others would do and would tolerate. How did you manage all of that into kind of a business plan that would make it work for Gemini?

FELSEN: Yeah. Well, we made up our mind at the beginning that amongst the things we wanted to do, you know, was like, quote, “everything you could do for an artist.” Including any process they wanted to try, any material they wanted to use. And we did. We did that. We’ve done it for— You know, we’re in our fifty-third year now, and we’ve never denied an artist anything that we wanted to try.

CUNO: So then what was your business plan? How did you make it work financially for you?

FELSEN: Well, let’s see. Let me go back a step. In accounting, one of the things that I was exploring and [had] gotten into a little bit, as far as for a small company, business management, right? You know, accounting was really about record keeping for many, many decades. But somewhere in that period—we’re talking about the early days of Gemini and just before that—accounting firms started having business management sections.

And so when Gemini started, I coined the phrase that you have to run this place like a business. And at the same time, you can’t run it as a business. You can’t take a creative organization, creative endeavor, and tell them they have so many hours to do something or so many dollars to do something.You would absolutely thwart the creative spirit. So our business plan was there was no plan. We wanted to work with the people we wanted to work with and to do it. You know, again, Stanley had a growing business and I had a business, so we had outside income. We weren’t wealthy, but we had funds.

CUNO: I remembered that you had a subscription program, whereby, I think, someone would pay a certain amount of money and would get a print from each of the series that you printed.

FELSEN: Yeah.

CUNO: Do I remember that correctly, and was it successful?

FELSEN: Oh, yeah. yeah. Well, what happened was—going back to, you know, the time difference. Like, the first project that Frank Stella did, the prints were seventy-five dollars. And Jasper did black and white numerals that were forty inches, I think, by thirty inches. Did a series of ten, and they were $350 each. And then the next year he did colored numerals, the same size, some of the same plates. And they were $800 each. And so a set of eight color numerals was $8,000. And Bob Rauschenberg did Booster. Again, the largest print ever in that time. It was a thousand dollars. And you know, it has sold for probably $350,000 for that one print. It was a different time.

CUNO: Was one part of the business plan that you chose to limit the edition size?

FELSEN: Oh yeah, going back to a subscription. So what happened was, we were an amazing success. Almost everything sold out. The editions were probably fifty. And so we created this subscription program. The idea is you buy one of everything we do and you get a 25% discount. And so what we want— what we were trying to do was build collections.

We thought it’d be great to have, you know, a dozen or so collections around the country or the world, of things that we did. I would say, if I had to guess, it was two or three years or we started to see what was happening. Some of these, quote, “collectors” were putting the prints on the auction or selling them in the market in some way. And it was really totally against the philosophy of what we were trying to create. And so we stopped the subscription program.

CUNO: Oh. How long did it last?

FELSEN: I’d say at the most, three years.

CUNO: Yeah. How has the market for prints changed over the last fifty years? Because there was a time in the sixties and seventies when it seemed to be just thriving. Every artist wanted to make a print, every collector wanted to collect a print. Is that still the case?

FELSEN: In a way, it’s hard to compare. But you know, oh like, say just to go back to 1966, when we started, the quantity of the artists, the quantity of collectors, quantity of museums, the quality of galleries, I mean, it was so tiny compared to what it’s become. The print market is tremendously active. But I’d say well, you know, some of the differences between then and now— In those days, you either bought a print from a publisher or from an art gallery. You know, these days between the art fairs, auction houses, and the internet or— You know, the belief is that the number of people coming into art galleries these days is much held down compared to earlier days, because of these other attractions and ways to do art business.

CUNO: Yeah. Now, you’re still working with young artists. And I think of Tacita Dean and Julie Mehretu as among the young artists you’re working with. Is that still what keeps you going, working with artists, younger artists?

FELSEN: Well, the reverse of that is the important-to-us artists who are no longer living are Roy Lichtenstein, Bob Rauschenberg, Ellsworth, Diebenkorn. I think we’ve worked with about seventy-five artists now, and over thirty of them died. And so you’ve got to do something. And so we’re always looking. You know, how do we choose artists? You go to galleries, you go to museums, you ask your friends, you ask artists. I regularly ask the artists who we work with, “Who do you think we should consider?” So like that.

There’s always going to be a need for looking for another artist. You know, like one example I think of quickly, we picked up with Elizabeth Murray at the airport one day. This was probably fifteen years ago. She says, “Oh, I’ve got an artist for you,” you know? “Who is it?” “Julie Mehretu.” I’d never heard of her. And so I went home and then amazingly, in the L.A. Times there was a box set or display out or whatever they call. It said Julie Mehretu was opening that night at the Redcat.

And so I— Joni and I called Elizabeth and said, “Well, let’s go see Julie’s opening at the exhibition.” And so we went that night and we introduced ourselves and started a friendship, which you know, led into a great relationship with— between her us. But well look, we’ve been busy since the day we started.

And one of the worst things that you can do as a publisher is have an artist come in and do proofing. Proofing session is when the artist comes in and does their part, the creating of the art itself. And they’ll usually last anywhere from one to four weeks. I think Roy Lichtenstein was a six-week to approve proofing artist; but otherwise, it was less than

CUNO: Does it happen then, if I understand the process, that an artist might come and initiate the printmaking process, then go back to New York or go back to where they are, and then come back and proof later?

FELSEN: Every time Jasper Johns came to Gemini, that’s what he did. Every time Bob Rauschenberg came, he finished. He never came back to start something. But there’s a lot of both of those ways, as far as proving sessions.

But in publishing, one of the most undesirable things that can happen is the artist comes in and does their proofing, leaves, and then we can’t get to the actual editioning until a long period of time. It frustrates the artist and it makes ’em angry because they felt like they did their share; now you should be doing your share of actually producing this work so they can sign it and it’s out in the world.

CUNO: You must have a tremendous number of stories about artists. You’ve already said some. What are some of your favorite stories about them, working with them?

FELSEN: Well, in Los Angeles, stories will evolve around movie stars. And so we became fairly friendly with Dustin Hoffman. Dustin was a, let’s say, a fairly serious collector. And so one time he— I don’t know whether he told us that he wanted to meet Bob Rauschenberg or Bob told us he wanted to meet Dustin. And so we made a date for them, that they would meet each other. They’d come to Gemini at lunchtime. And so Joni was up in front and Dustin came in and he sat down with her and he said, you know, “How do I— How do I look? Am I okay? Am I [inaudible]?” And I was in the shop with Bob and Bob, “How am I? How am I doing? It’s my time.” Oh, Bob made a paper bow tie to wear. And so we introduced them, you know, and they went off halfway on their own lunch, and we both laughed. You know, we each told each other what the other had been doing. So that was one.

Let’s see, Norman Lear would have a, like a preview, showing a movie at his house every Sunday night. So he invited us to come over and to bring Bob Rauschenberg with us. Bob was at Gemini at that time. So we did. And Gregory Peck was there. And so Gregory Peck and Bob found each other at the party, and they spent the evening talking about creativity. And so— and so I guess Bob tells Gregory Peck to, “Why don’t you come in and, you know, keep me company or we get talk.”

So the next morning the phone rings and this voice says, “Sid, I don’t know if you remember me, but this is Gregory Peck.” And so I said, “Yeah, Gregory, I remember you.” So he said, “Well, Bob told me I could come in and be with him when he’s working.” “Yeah, come on in.” So it was August. And we have a big patio, and we had set a, like a scrim across the top so the artists could work outside. And Gregory showed up about noontime and Bob was working on chairs. He was making brass chairs and they were fabricated. And then Bob was taking dyes or paints and he was painting the material. And so for six hours, you know, Bob would walk and Gregory would follow him across. And they’re were having a great time and, you know, and the Jack Daniels was flowing. And for me, it was sort of a miracle to watch this. These two characters, the way they were interacting. But they kept talking about creativity all the time. They were seriously involved in the subject.

I remember one time, David Hockney you wanted to meet Billy Wilder, and Billy Wilder wanted to meet David. And so I arranged a luncheon. The three of us want to Spago. And they were so excited about meeting each other that it was like— You know, sometimes on a tennis match, where you watch where the ball goes this way. It goes to the right and then to the left. And so they started talking to each other. And you had the feeling nobody was listening, because they both kept talking all the time, you know? I’m just sitting here, and they were to the left and right of me. And this went on for, I don’t know, one or two hours, where it was just amazing, just watching the activity.

CUNO: Did it result in anything?

FELSEN: Oh, yeah, they became good friends.

CUNO: Yeah?

FELSEN: Yeah. It went well. David did a series called Friends, and he invited twenty-two guys, I think, twenty-two guys to sit for him. And they were very serious sittings, like two or three days.

CUNO: That was fairly recently, right?

FELSEN: It was 1976.

CUNO: Oh, that early? ’Cause he did it again recently. And I think you were the subject of one of those prints.

FELSEN: Yeah.

CUNO: Or one of those paintings anyway.

FELSEN: Well, the way that happened, a lot different than the way it happened— You know, David, in the last many years, is totally involved in digital, as far as printmaking. And so Joni and I went up to visit him. And he asked me to sit in a chair and he took my picture. And the same day, I think, he asked Joni to sit in a chair. And the next thing we saw, he sent us a picture with about twenty people. We were all sitting in chairs. He made a print that was, I think, thirty-six feet long. You know, machine-printed. It was huge.

CUNO: Now, you’re a photographer, and you’ve been taking photographs of life and work at Gemini since it opened, I think. Tell us about that and about your interest in photography.

FELSEN: Well, look, as a teenager, maybe even before a teenager, I got interested in photography, only in the sense of a little boy who read magazines or I used to read photography magazines. And with a neighbor friend of mine, we decided we want to set up a darkroom. We bought a book on what to do, as far as processing film, black and white film. And used the bathroom in my parents’ house. We made pictures. And then in World War II, I was a GI, and I was stationed in Europe for twenty-three months, and I took a lot of fun pictures, so to speak. And so when the war ended, I was stationed in Paris. They had these— They were like you’d call ’em black markets, I guess. The European people had a lot of cameras. And we had chocolates and cigarettes and stuff, so you could trade. Good deal for both sides. So I did trade for a better camera.

So when Gemini started, again, Ken Tyler ran the shop and I ran the administration and sales. And I really didn’t have the confidence in myself as a photographer to try to take pictures of the artists. But the Tyler hired— Well, Malcolm Lubliner[sp?], his photos, they’re in part of the Getty collection. So well, for the first, well first five years, Malcolm was a Gemini photographer.

CUNO: Oh, documenting the artists at work?

FELSEN: Yeah. From ’66 to probably ’71. But then Tyler left Gemini in ’70— Well, the beginning of ’73; but by ’72, he was pretty much out of there. I still was timid about doing ’em. I didn’t think I was that good. So what I started doing was photographing the printers. And I suddenly got my confidence. And then Bob Rauschenberg was the first artist that I photographed in the shop. And he was very kind and very encouraging, saying, “You know, your pictures are really good. When I look at them, you capture something that I really appreciate.” And so that gave me a certain amount of confidence. And so then I started. But when you look back at my early pictures, they’re not great.

The thing is I had this audience. I feel like my photography collection has certainly— one strong element is the friendship with the artists.

CUNO: Yeah.

FELSEN: ’Cause Bob Rauschenberg was my first pal, you might say, amongst the artists; but then, you know, pretty quickly became strong friendships with a lot of the artists. And as I did, I got more confidence. You know, I felt it’s one thing to have a hired gun who comes in and photographs; and I think it keeps the subjects a little bit maybe ill at ease by this outsider. But in my case, I had a friendship. And I always asked, them and they always said, “Oh yeah, sure, absolutely.”

Every time I took a picture of an artist, I would send them a print. And I had a few times where the artist said to me, “You know, I didn’t even realize you were taking my picture.” You get a whole ’nother message that, you know, again, I was buying Leica cameras because on the range finder cameras, the shutter is so quiet you probably don’t hear the— Whereas a single lens reflex—whoom—you hear that clumping and all.

CUNO: Yeah, yeah.

FELSEN: And I sort of tiptoed around. Well, you know, then later on, I started really understanding more about photography and my pictures, probably the last twenty or twenty-five years, got much better.

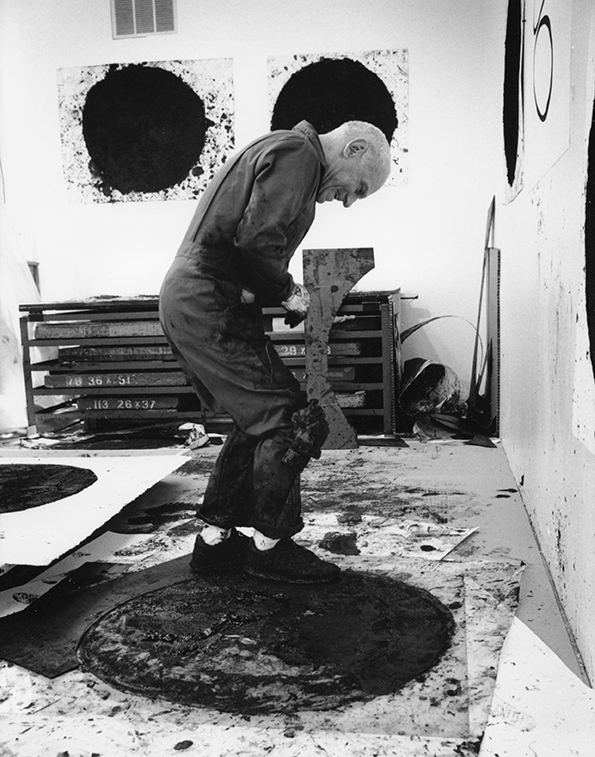

CUNO: Well, I’ve got a book of your photographs here. And I’ve identified three that I like, three of the photographs that I like very much, and I wanted you to talk about them. This one is showing Richard Serra. There’s this two-page spread, and Richard is making prints of rounds, pouring this pigmented material on to the—

FELSEN: Yeah, yeah, okay.

CUNO: To this paper, or onto something. Tell us about this and describe it for us.

FELSEN: Yeah. Well, Richard is an amazing collaborator, in that he gets into it and he gets all the printers really into it with him. We have a etching studio, we have a lithography studio, we have a screen printing studio, and we have a Richard Serra studio. Richard is so active in printmaking. He’s done 325 editions with us now.

CUNO: Wow.

FELSEN: And everything is black and a lot of the subject interesting to him is texture. In other words, he makes his own drawings, but he wants his prints to be different than his drawings. And so here, those items on the floor are aluminum plates. Well, they could be copper plates. I think maybe they’re copper plates. And so Richard puts paint stick on the plate. And then it—

CUNO: Which is a waxy, tacky substance.

FELSEN: It’s a crayon. It’s soft and very tacky. And it’s very moldable. It’s very easily shaped. And so he— I had a big collection of jazz records, and he likes rock and roll. Sometimes he brought his own records in. And so he plays the music real loud, and he starts dancing on top of the plates. He’s creating texture from the bottom of his shoes. And so you’re watching this phenomenon of an artist creating texture by dancing to rock and roll.

CUNO: And there are two prints attached to the wall behind it. Had they proofed those prints? Is this what these prints are going to look like?

FELSEN: Yeah. And that’s in the artist’s studio, so anything on the wall is something he’s working on right now.

CUNO: Mm-hm, mm-hm.

FELSEN: At that time, I mean.

CUNO: Yeah. What about this photograph? Photograph of Jasper attending to a crosshatched print? And he’s— it’s his striped shirt, the combination between the striped shirt and the crosshatch on the printing that—

FELSEN: Yeah, well, that was the attraction. To look at the two different designs clashing with each other, so to speak. The crosshatching and this very striped shirt. So he was molding the image itself embossing in it. And so he’s pounding on an embossing plate to get the shape he wants.

CUNO: But you were interested in the play of the lines.

FELSEN: Yeah, we’re looking at— You know, it’s very, very normal, say Jasper or an artist is in the studio working. I felt I will follow them around. I usually, before digital came in, I had three cameras. One was black and white film, one was color film, and one was slides. And so I would follow the artist around. As soon as I saw something that looked interesting, I’d start photographing. And that happened to be a very visually interesting moment.

CUNO: What about this photograph. Ellsworth Kelly and you.

FELSEN: Well, everybody wants to into the act. And so I figured out by the use of the mirrors, that I could get Ellsworth and me both in the picture. So that’s photographed into a mirror that reflects off of that, so—

CUNO: So we have Ellsworth Kelly on the left side of this two-page spread, looking into the spread, and then turning his head to the right. And you’ve captured that on the other spread by the reflection in the mirror, so we’re seeing his right side of his face on one side, left side of his face on the other. And there’s a round mirror on the table, and you and your camera are dead center in the round mirror.

FELSEN: Yeah. The mirror was sort of a standard item in the shop, because artists like to use mirrors a lot of times and—

CUNO: Because the print prints the reverse.

FELSEN: Reverse.

CUNO: Yeah. Well it’s terrific. You know, and you’ve compiled this great archive of artist photographs, photographs of artists, and we’re very happy to have that now in the collection of the Getty Research Institute, thanks to Jack Shear, who made it possible. And Jack Shear, of course, is the husband of the late Ellsworth Kelly.

FELSEN: Incidentally, just as an add on, Jack Shear was a partner, owner of a photo lab called Photo Impact. Began in the days of film. I would have my— all my black and white film done at Photo Impact.

And so one day I just said Ellsworth, “Keep me company. I want to go drop off this film.” And he said, “Yeah.” So we drove down there. And Jack Shear was behind the counter. And like if you ever see these magical moments where two people look at each other and the sparks start to fly. And the sparks started to fly. And I’d say within a few months, I lost my lab man, who moved back to upper state New York, and lived with Ellsworth for many, many years.

And then I think it was Ellsworth’s birthday, probably 2010 or something like that, that— In the morning, Ellsworth said to Jack, “We’re going to get married today. “And they got married. And they stayed married for five years, until Ellsworth died, so—

CUNO: Yeah.

FELSEN: But I felt that I helped create a very important romance.

CUNO: Well, which led to the archive of your photographs coming to the Getty. And we’re very pleased and grateful to you for that, and also grateful, of course, to Jack, to make possible. So Sidney, thank you for your time this morning.

FELSEN: Thank you.

CUNO: This episode was produced by Zoe Goldman with audio production by Gideon Brower and mixing by Myke Dodge Weiskopf.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music.

Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other podcast platforms.

For photos, transcripts, and more resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Or if you have a question or idea for an upcoming episode, write to us at podcasts@getty.edu.

Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

SIDNEY FELSEN: You can’t take a creative organization, creative endeavor, and tell them the...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.