Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1854, Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869). Hand-colored albumen silver print. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013

At age 17, Alexandrina Victoria, soon to be Queen Victoria, was in a bit of a quandary. While she knew that finding the proper husband was one of the most important decisions of her life, she was also feeling the pressure to walk down the aisle. In less than a year her uncle, William IV, would die, and she would be crowned as queen. It seemed only proper that she find a suitable mate to share in her reign—but it was slim pickings in the royal line.

That is, until she met Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Technically he was her cousin, but Albert’s uncle Leopold thought it was a good match. They met in 1836, and afterwards Victoria wrote in her diary:

The Queen and Prince Albert, 1854, Roger Fenton (English, 1819–1869) and Edward Henry Corbould (1815–1905). Salted paper print, hand-colored. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013

“[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large & blue, & he has a beautiful nose, & a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful”.—Queen Victoria’s Journal, May 18, 1836

Thus began one of history’s greatest love stories. Their courtship lasted until 1839, when Victoria proposed to him—as was the proper custom—and they tied the knot on February 10, 1840. Although she spent their wedding night in bed with a headache, she wrote:

I never, never spent such an evening!! My dearest dearest dear Albert … his excessive love and affection gave me feelings of heavenly love and happiness, I never could have hoped to have felt before! He clasped me in his arms, and we kissed each other again and again! His beauty, his sweetness and gentleness, – really how can I ever be thankful enough to have such a Husband! … [to] be called by names of tenderness, I have never yet heard used to me before – was bliss beyond belief! Oh! this was the happiest day of my life! —Queen Victoria’s Journal, February 10, 1840

That is some serious devotion.

What makes the love between Victoria and Albert so unique is that it was the first to play out in front of the camera—a story told in the exhibition A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography. The exhibition features substantial loans from Royal Collection Trust, including several photographs created as personal souvenirs and never meant for public view.

In January 1839 Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced the invention of photography, and William Henry Fox Talbot followed quickly with his own claim to the medium. It is known that Victoria was shown photographs by Talbot as early as 1839, and just a few years later Victoria and Albert were collecting daguerreotypes.

The Crystal Palace at Hyde Park, London, 1851, John Jabez Edwin Mayall (British, 1810–1901). Daguerreotype. The J. Paul Getty Museum

For royals to take an interest in such a young medium meant that photography could only grow in popularity among the general public. Victoria and Albert amassed a large collection of private and public photographs, and the public ones were distributed as easy-to-transport cartes de visite (calling cards) during the 1860s. For the first time in history, the public could carry around actual pictures of the royals in their pockets, or admire them on a wall. In 1851 Victoria and Albert presided over the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, which featured nearly 700 photographs as part of an international celebration of art, invention, and culture. They also had practical concerns about photography, such as fading, and donated funds to the Photographic Society of London to establish a “Fading Committee” to investigate the causes.

More than an art form, photography became a mutual hobby and expression of affection for Victoria and Albert. They would sit for both private and publicly distributed portraits, arrange photo albums, and give each other prints as gifts for birthday and holidays. Even their nine (nine!) children got in on the act, and they were often photographed individually and as a family.

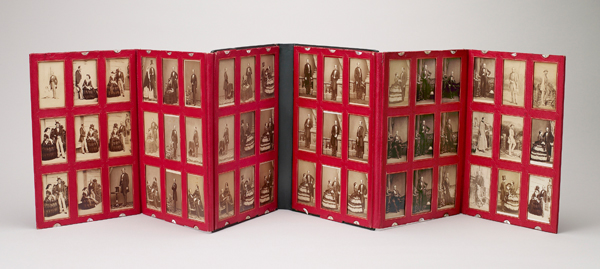

Folding portfolio containing portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (1859–1861), Camille Silvy, John Jabez Edwin Mayall, Frances Sally Day, William Bambridge. Albumen silver prints. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013

In 1854 Albert was photographed by Bryan Edward Duppa, and as a birthday present to Albert, Victoria had herself photographed by Duppa while holding that same photograph. Très romantique.

Lovebirds. Left: Portrait of Queen Victoria Holding Portrait of Prince Albert (negative, July 1854; print, 1889), Bryan Edward Duppa (English, 1804–1866) and Gustav William Henry Mullins (English, 1854–1921). Carbon print. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013. Right: Portrait of Prince Albert, 1854, Gustav William Henry Mullins (English, 1854–1921) and Bryan Edward Duppa English (1804–1866). Carbon print. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013

In 1861 Albert died suddenly, leaving Victoria a widow at age 42. She embarked on a long period of mourning in which she withdrew from public life. Even in death, Albert never left Victoria’s side in photographs. In this 1862 photograph, Victoria is seen seated, dressed in black, and gazing at a picture of Albert. Other photographs feature a bust of Albert present with the royal family.

Portrait of Queen Victoria Seated, Gazing at a Photograph of Prince Albert, about 1862, Ghémar Frères. Albumen silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum

While Victoria and Albert’s love story was tragically cut short, their devotion to photography offers a vast historical record of their relationship and family life. On this Valentine’s Day, we celebrate a royal match whose relationship remains a model to this day.

Comments on this post are now closed.