André Malraux, the French novelist, minister of cultural affairs, and art theorist, published his seminal book Le Musée imaginaire in the early 1950s. In The Book on the Floor: André Malraux and the Imaginary Museum, art historian Walter Grasskamp takes Malraux’s work as a launching point to explore Malraux and his contemporary André Vigneau, the early history of the illustrated art book, and how Malraux’s vision for a “museum without walls” anticipated a new approach to art history that was comparative and global in scope. Thomas Gaehtgens, director of the Getty Research Institute, joins the conversation.

More to Explore

The Book on the Floor: André Malraux and the Imaginary Museum book

Transcript

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

WALTER GRASSKAMP: He discovered that on two pages of a book, you have the possibility of comparison. That inspired him to combine the different artworks from different sources, from different countries, from different traditions, and this really make him kind of drunk by his own enthusiasm.

CUNO: In this episode, I speak with Walter Grasskamp, art critic and former chair of art history at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich, and Thomas Gaehtgens, director of the Getty Research Institute, about Walter’s new book titled The Book on the Floor: André Malraux and the Imaginary Museum.

The Getty publishes some thirty books a year deriving from or relating to the work of its museum and academic programs. Today we’ll talk about one such publication, The Book on the Floor: André Malraux and the Imaginary Museum. Malraux, the French novelist, minister of cultural affairs, and art theorist, published his seminal book Le Musée imaginaire in the early 1950s. Walter Grasskamp takes Malraux’s work as a launching point for an inquiry that is as much about the history of illustrated art historical texts and the place of Malraux’s books in that history as it is about a particular kind of art history, a transnational comparative art history, a way of looking at works of art across national borders.

Walter joined me and Thomas on the phone from his office in Munich. I started by asking him what it was that inspired him to write this book.

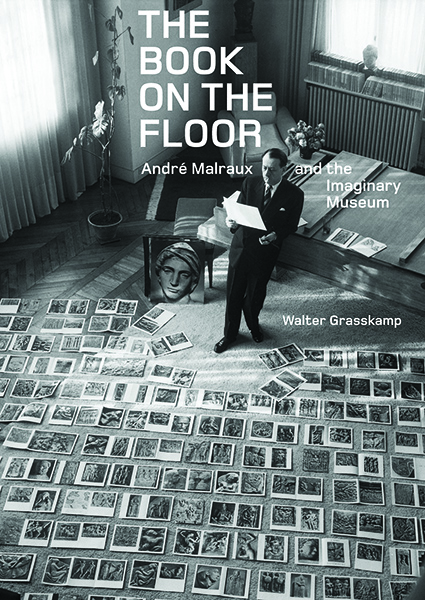

GRASSKAMP: I began with wondering about a photograph. And this is the photograph that is in the center of my book, a photograph that I think every art historian knows, at least in our generation, showing a gentleman in a Paris salon, looking over a hundred sheet[s] of printed paper, double spreads of a book he’s working on. A photo that is very ubiquitous in art historical literature of our days, but never printed very correctly. And so the first time I saw a complete print of this photograph, I admired it first. And then I wondered why all the illustrations laying on the floor were in the opposite direction to the person who was overlooking them. And so I wondered, what is he doing here?

CUNO: Meaning that the images are visible to—

GRASSKAMP: To the—to the viewer of the photograph, but not to the person photographed. And I think immediately, everybody who saw this photograph estimated that he was preparing the book, overlooking the production, rearranging the layout, whatever. But the situation was not according to this task. And so I wondered, what is he doing here? And it’s easy to find out that he’s not doing work, but he’s representing work. And that made me a bit skeptical about this form of self-representation of a famous art historian of his time, and I began to think about this photograph. That was actually the starting point of the book. It could have been an essay about a photograph. But then it turned out that there are so many themes entwined in this situation, and that the person who is in the center of the photograph is a very controversial and ambivalent person as well as a very prominent-in-his-time and fascinating figure. And so I had to deal with his biography not only as an art historian, as which he is representing in this photograph, but in his many-faceted roles that he played. And it’s very difficult to just make a short story of it. But I think there are some stages that are very important. And one is that he started as—not as an art historian, becoming one of the most prominent art historians of his time. He didn’t even study art history. But he was a young man when he entered the Parisian scene of boheme and avant-garde, and was very soon acquainted with Max Jacob. That’s in the 1920s. And he very soon began to be interested in making books. And so he started to edit books for publishing houses. And the second house that he came acquainted with was Gallimard of all editing houses, and this made him somebody who was, as well, dealing with art history as making art history by making books. But at the same time he was kind of an adventurer and never on a spot for a long time, and he took long journeys to South Asia. And on these journeys, he did something that made him not famous but notorious. He picked up pieces of reliefs in nearby Angkor Wat in Cambodia with a clear decision to sell them in Europe or in the United States for a market that was existing and that was very hungry and was, it seemed, easy to be fed. And as far as we know, even gallerists in—European gallerists were involved in sending him there and asking him to bring over some of these pieces. The market for world art as we call it today was at the time expanding. But he got caught. And so he was arrested together with his wife who was accompanying him. And after some time, his wife was able to go to Europe and organize some committee of solidarity and Malraux got free. And after coming back to Paris he immediately went back to Cambodia because now he was upset about the colonial circumstances in which the French ruled Cambodia, and was part of—the founder and part of a newspaper that was clearly anti-colonialistic.

So it’s a figure who changed his aims and his appearances in very short time. But all the time, he had the ambition not only to be an editor and a writer and—and he was a gifted writer as a journalist, as well, and he was a gifted person for dealing with photographs for the magazine that he did in Saigon. But most of all, he was ambitious to write his own books. And so he became a novelist—a famous novelist—with stories about South Asia where he was shortly before. It was the man’s fate—

CUNO: [over Grasskamp ] Yeah, and that—the Chinese Revolution, of the beginnings of it.

GRASSKAMP: Yeah, where he claims or at least suggests that he was involved in the preparation of the Chinese Revolution which he never was. But more important is La Voie Royale—I don’t know the English title; maybe The King’s Way or The Royal Way.

CUNO: Royal Way, yeah.

GRASSKAMP: [over Cuno] Which is about the story when he was in the jungle trying to steal these reliefs. And he makes it a story of securing them for his novel. So he’s a person that from the start invents his own life as well as living different roles. And after that, he comes back to France. He joins the Spanish Civil War—on the Republican side, of course, because he was, at the time, more or less part of the socialist-communist-bohemian scene in Paris. And staged himself as an officer of the Republican army, responsible for the planes, never having a pilot license himself. And after that, he went to the Resistance and he fought against the Germans. Nobody knows how long, how engaged; it’s disputed in the literature.

After he has published a lot of his own books and published a lot of books as editor in the Gallimard publishing house, now he becomes, after the war, the minister for—of information for Charles De Gaulle, a role that perfectly suits him and his vanity. [laughter] But what is most astonishing till today is that his life was adventurous enough so he would not have to invent a lot of other legends and stories and myths. Which he did and which makes his biographers busy up to today just demystifying all the myths that he invented to brush up his position which was fascinating as it was without all these legends.

CUNO: Okay. Now let me bring Thomas into this discussion because of course Thomas is a specialist in the history of French painting and culture. Thomas, what do you make of Malraux and of his reputation in France? And does any of his reputation, as Walter’s just given it to us so clearly, does it affect his reputation as an art historian or how we think of him as one and what he’s—and the books that he’s written?

THOMAS GAEHTGENS: Well, the reception is very different in France, in England, in Germany, and the U.S. One can say that generally, there was a great interest in his publications after the Second World War. I’m not talking about the novels, but I am talking about the art history books. However, he was not really accepted as an art historian—or let’s say an academic art historian. He never studied art history, as Walter says, he seemed to connect to earlier periods of art history, to Wilhelm Worringer, and first stepped into kind of a comparative art history, times when anthropologists were interested in art, like [Ernst] Grosse, Leo Frobenius, for example. And the idea of world art was heavily discussed by others like Karl Woermann who edited three volumes about the history of art of all times and all peoples already published in 1904. After—

CUNO: [over Gaehtgens] So he was building on a prior bibliography.

GRASSKAMP: [over Cuno] He was building on a[n] earlier time. And after the war, Malraux inspired a whole generation. And especially in Germany. Also Arnold Bode, the founder of the first Documenta in 1955. In Germany and France, we can discover recently renewed interest in Malraux. Authors and scholars like [Georges] Didi-Huberman, Henri Zerner published about him, but also several PhDs have been published about him in Germany. They focus more on Malraux using photography as a medium and compiling these images into a new way of transferring or better provoking an immediate aesthetic reaction of a common, let’s say, universal aesthetic.

CUNO: Yeah. And that’s really what Walter’s book is about. It’s not so much about Malraux the mythomaniac, as others have called him, but it’s about the making of his books and particularly the one book, The Museum Without Walls, as it’s called in English, Le Musée imaginaire, and the role that illustrations have played in the writing of such history. Walter, tell us about the origin of Malraux’s project, about his book, Le Musée imaginaire, which early on, you call his “art album,” to distinguish it from a book, I assume. And of course, it is related to the title of your book, The Book on the Floor, it is that book on the floor.

GRASSKAMP: Yes, it is. I think talking about Malraux we have to differentiate between the writer and the editor. The writer is completely different from the editor. The editor is very matter of fact, very intelligent in his editing work. The writer is very pathetic, pathos-laden, very enthusiastic. And it’s close to a kind of self-excitation to—when you follow his writing. And it’s very tiring, on all the pages that he’s written, to follow him in this kind of enthusiasm. And I think this more or less damaged his reputation in the academic world.

But on the other hand he wrote about the media, about photography, about cinema earlier on than any art historian or Wissenschaft, as we say today in Germany, has done. He was not only focused as art that—as it is seen in the museum. So that makes him a very interesting person in the art historical text—the context. But on the other hand, what makes his renommé today, at least to me, is that he discovered the images as the central element of art publishing, of art mediating. Working in a publishing house like Gallimard and seeing the products of other publishing houses, he was among the first to see that the possibility to print black and white photographs of art in books would make a new market that made Gallimard famous in France. And this is mainly his merit, I think, that he did so. And he discovered that on two pages of a book, you have the possibility of comparison. That inspired him to combine the different artworks from different sources, from different countries, from different traditions. And this really made him kind of drunk by his own enthusiasm, because now he—the possibility of comparison given on the double spread of a book, he was taken away from these possibilities of comparison, and made a kind of visual thesis about world art that came into fashion not only by art historians about texts, but that he made a fashion in illustration as well. And so what I called an art album, or more or less Fiona Elliott, who made a good translation, called the art album—would be kunst bild buch in Germany—that’s very difficult to translate. It’s an image, an art image volume. If you translate it literally, it would sound stupid. The art album is a book that is not focused on text with illustrations but on images with commentaries. And that’s the decisive change that he did not invent.

CUNO: Yeah, we should clear for our—for our listeners that if you can ima—the listeners can just imagine before them, a book open to a spread—one page on the left, one page on the right—sometimes it’s putting an image, a photograph of a work of art on each, the left and the right, and making a point about that comparison. Other times, it may have multiple images left and multiple images right. But it is the argument based on comparisons side by side, of similarities and differences between them. I want to get to that in a—in a minute, but I want to get back to the point of that comparison, which is the point of opening up one’s understanding of the world’s art history across national boundaries, and looking for relationships that exist between European, let’s say, and Asian. And that was a contribution that he built on earlier precedents. Thomas, did this structural basis of comparisons have any relationship to university-based art history in Europe at the time?

GAEHTGENS: Well, I think we have to distinguish different directions in art historical scholarship. One is very seriously devoted to analysis based on historical context, stylistic comparisons, iconographic tradition. In a certain way, academic art history. Others—not only art historians, writers on art—after 1900, were interested to explore the idea of world art. These were often museum curators like [Alfred] Salmony who was a curator in Cologne who met Malraux in Paris; or authors like Carl Einstein. These scholars or writers were inspired by dealers like [Alfred] Flechtheim, [Daniel-Henry] Kahnweiler; [Michel] Leiris in France; collectors like [Eduard] von der Heydt, [Karl Ernst] Osthaus, and others. And of course, one should not forget the reception of Oceanic and African art by modern artists from Cubism to Surrealism. So in a certain way Malraux was very much aware or even part of this artistic scene.

CUNO: Yeah. And I guess as Walter’s pointed out, it’s integrated between the university, the museum, and the marketplace or—and the artist’s studio, in which there’s a common interest in relationships across national borders. But did it have an implication for how one wrote a new art history? Or was it just how it provoked an understanding of current practice in art history or current opportunities in museums? I mean, what is the—what is the intellectual legacy of this enterprise?

GAEHTGENS: The intellectual legacy is not a legacy to academic art history first, but it is an extremely important legacy to understand that a Eurocentric interest on art history changed. And this was, especially after the Second World War, a very, very important new element in the discourse. And the younger generations, especially after World War II, were very much interested in looking beyond Europe, and they had suddenly the feeling that there was more to understand and to analyze, and bringing these other worlds into contact with European art. And that’s what, in a certain way, Malraux did in his albums.

CUNO: Yeah. And important to Walter’s thesis in the book is the role that photography plays in the development of art history books. And Walter, you mention Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” and its influence already on Malraux when it appeared in a French translation from the original German in 1936. Tell us about Malraux’s response to Benjamin’s essay and its effect on his conception of Le Musée imaginaire project.

GRASSKAMP: Malraux was often criticized for producing all these legends and myths about his life, and it’s not easy to defend him in this respect. But I think he should be defended in one of the myths that art historians created and prolong, that he did plagiarize Benjamin, if that’s the word. He knew Benjamin, and he heard of Benjamin’s thesis about the reproducibility of art as a very important change in the reception of art. But I think he came to the same conclusions from a different angle. He was producing books, he was producing reproductions, he was editing reproductions, he was playing with reproductions of art, and he discovered this game on his own. And so he was possibly one of the first to be able to understand what Benjamin was about, because nowadays, this essay is one of the main essays of the twentieth century. But I doubt if, at the time when it was published, very many people would have understood what Benjamin was after. And so I think they met on eye level, if I can put it this way. But he never mentioned Benjamin after two essays, never in his books. But this fits into his normal way of ignoring and not mentioning influences that of course he had.

GAEHTGENS: [over Grasskamp] He never quotes. He never quotes his sources.

GRASSKAMP: He never quotes. No, he’s fascinating by an originality that he had but that he augmented by others. [chuckles]

CUNO: Well, you make the point, Walter, that Benjamin was interested in photography and in this concept of the mechanical reproduction of works of art from a political, theoretical point of view. And of course, Malraux is interested in it from a commercial perspective.

GRASSKAMP: Yes. I think we can put it this way. But what the—one of the results of my book that I was surprised with myself was to find out that Benjamin himself referred to a model of publishing photographs on art that he doesn’t mention himself in his essay but he could have mentioned. And this is the encyclopedia that André Vigneau published since 1936. And which appeared at the same time when Benjamin wrote this essay. An encyclopedia that sounds like an encyclopedia, but in fact, was a book of illustrations, of hundreds of illustrations with very few commentaries, that Benjamin must have known. But I never could prove that there was a connection between both of them—both worked in Paris at the same time—till I found, in the youngest edition of Benjamin’s collected works, there is a hint that he was working on a review of an encyclopedia in 1935, which obviously was the start of his essay when he began to think about the reproducibility of art through photography. And this was an encyclopedia where Vigneau was published, and the name is mentioned, so Benjamin knew what Vigneau was doing and that Vigneau was one of the theorists of photography.

And the essay of Vigneau was called “Les besoins collectifs et la photographie” that was more or less the same position from which he worked. And so I think it’s much more interesting to see Benjamin in relation to Vigneau than Malraux in relation to Benjamin. This was one of the results of my book that surprised myself, and I think which is one of—of one of the crucial points, that the book can give a new view on how this thought transference worked on—in Paris.

GAEHTGENS: But what is very striking is, of course, your comparison of Vigneau and Malraux. And it is absolutely clear that Malraux started from Vigneau. However, I think it should be very clearly stressed that Malraux’s idea why he didn’t quote Vigneau was that his start was completely different. Vigneau only had photographs from one collection, let’s say from one museum. Mostly, by the way, from the Louvre. But the idea of Malraux was, of course, to combine very different sources. Is that correct?

GRASSKAMP: That’s right. That’s right. Malraux, we should mention as well, was not—he did not come to an art history that is combining different traditions, different nations, different cultures, by reading or by visiting museums, but by traveling. He is a person that was inspired by his own traveling to Asia and made his connections much earlier than the art world did. And of course, Vigneau focused on the Mediterranean. It’s a classical position to make an encyclopedia of art that focuses on the Mediterranean and starts with Greece and the Roman culture and Egyptian culture while Malraux from the start had a much broader horizon and was inspired by what he saw on his travels, as well [as] by what he saw in the museum. That’s right.

CUNO: And Vigneau was himself a photographer, is that correct?

GRASSKAMP: Vigneau—I should have co—I should have written a book that would have been called André Malraux and André Vigneau, because Vigneau is more or less forgotten. He is very important as a source of inspiration for Malraux. He was an art editor before Malraux became an art editor. And the encyclopedia of—the photographic encyclopedia of art that Vigneau started in 1935 is a very important date in the history of the development of art books and art mediation. But he’s more or less forgotten even in France. It was very difficult to find out about him. And he, on the other side, is as multifaceted a person as Malraux was because he began as a sculptor very early, was a trained artist, a very promising artist. But then turned to music and playing the cello in the cinema with all these films that had no sound at the time. People say he was not a very good cello player, but at least it was the way he earned his money. And he began to deal with photography as an amateur, and then went into professional studios and became a very well-known man for advertisement photography and he made his living from that.

He came into the focus of a Paris publishing house that was establishing a program of photograph-based art books. And he was the main contributor to this program, Éditions “Tel,” as Malraux was to Gallimard; but he was earlier than Malraux. And after that he went to Egypt and became a manager of a film production and then ended up in television. It’s a life as fascinating, as different as Malraux’s. No politics. No politics in it; that’s interesting. But he is completely forgotten. So I could have stressed in the title of my book much more than I did that this book is also a rediscovery of André Vigneau.

CUNO: We should remind ourselves that while we’ve been talking about Malraux and Vigneau and we’ve been talking about the thirties and the forties, that some of the reproduction of works of art in books about the history of art date slightly earlier—let’s say 1920s and thirties—but certainly between the twenties and the fifties is the time in which there’s a di—a creation of a number of books about history of art that are accompanied by rich illustration. And now we take it for granted that illustration of books about art history, whether printed or increasingly more digital, will have great images associated with them. But Thomas, can you tell us about how revolutionary it was in the thirties to the fifties to have these substantially illustrated books on the history of art? And were they equally attractive to a general public as they were to scholars or was it more to the scholars than the general public?

GAEHTGENS: Well, as Walter has convincingly demonstrated, some of Malraux’s books and especially the one Malraux is standing on in this iconic photograph is in a certain way not an illustrated book. I would like to stress this difference. It’s not an art historical book which—with illustrations, as [Heinrich] Wölfflin’s Principles of Art History or any other book. They are albums on the basis of comparison mostly with very short captions. He was criticized for this. There is not a lot of basic information. The illustrations are facing each other and seemingly have some kind of resemblance, or the work of—the works of art have some kind of resemblance, although they illustrate works of art or details from very different backgrounds, times, and cultural context. And they are sometimes taken out of the context, so you have no idea of the proportions, of the sizes, in the comparisons. This is the difficulty. Comparison might or might not be evident. And above all, what to make with the resemblance?

For an art historian, the resemblance is more or less for—I am talking about a academic art historian—the resemblance is more or less sometimes a random choice. As I already mentioned, Malraux never studied art history; however, Malraux was a magic collager. He offered images of cultures never seen in combination which are striking, astonishing, sometimes disturbing. If you like, one could say that the albums represented a collection of works of art of the same level of beauty overcoming traditional hierarchies; European and non-European art combined; a respectful vision of global art. Would you agree, Walter, with that?

GRASSKAMP: Yes. Abs—I couldn’t have—I couldn’t have said it better. [chuckles] That’s absolutely right. It is the idea that instead of visiting the museum from room to room, you sit at home and you turn the pages and you go from image to image, from picture to picture, from sculpture to sculpture, just by turning the pages. Not disturbed by too much commentary, fascinated by superficial and/or essential similarities, and of course, in a way that is completely ignoring scale. I think this is something that Vigneau saw different. Vigneau’s—Vigneau is not only important as the inventor or producer or maker of the Encyclopédie photographique de l’art, but he’s also a very good photographer, and he’s very ambitious to give sculpture a realm, a space in which it can function even in photography which of course is two-dimensional. While Malraux, on the other hand, is trying to—he has a magic grip as Thomas has said, and he tries to put this magic into the lighting and the situation in which this art is photographed. And so he’s mystifying a lot of art pieces that, from themselves, would be interesting enough to be not mystified, while Vigneau is always very matter of fact. And he’s very not only ambitious, but very serious about what he’s doing while Malraux is fascinating by himself and by the possibilities that are open to him with making books. And it’s important, of course, to—Thomas already mentioned—to stress that Malraux began from a different point. He made—first he made books with illustrations. The first, Musée imaginaire, was a book with illustrations. And when Gallimard took over les Éditions “Tel,” for the first time, he changes completely. And it’s obvious that Vigneau gave the model for making—to making books with images in the foreground and texts and commentaries in the background. Afterwards, he returned to what he originally made. But for this book on the floor—and this is the book which is more an appropriation of Vigneau’s model—he was in Vigneau’s shoes, more or less, without mentioning him in the first volume. And this is one of the points of the first volume was The Book on the Floor, this is one of the points that are important, that in the credits of the photographs at the end of the book, some photographs are mentioned as authors but Vigneau is not. And so it’s one of the points where Malraux’s habit not to quote turns out also as a habit not to respect what other people have done before him.

GAEHTGENS: But Walter, can—may I just add one point to this? You know, he didn’t quote Vigneau, but it was evident that he used his books. On the other hand, Malraux even went further—he manipulated the photographs. So he changed the backgrounds or he turned them even in another direction. So he really interfered in the photographs. So he was an artist with these photographs in a certain way. He used Vigneau, but he changed Vigneau. So we have to then stress his own way of dealing with these photographs. And he is the author, in a certain way, also of these photographs.

GRASSKAMP: That’s right, in the way he appropriates them. That’s right. What I would like to add to the—what I said before is that it’s about time that somebody who is familiar with French culture, with French language excavates Vigneau’s legacy which is in the Paris library as a legacy and give him more publicity than I do with my book. My book is just a hint at what he did. But I think it’s about time somebody starts to decipher all the notebooks that he left there, an put him in the place that he deserves to have.

CUNO: You know, Walter and Thomas, one of the legacies of this kind of photographic layout, with images on left and right, in this two-page spread of a book, has to be the use of slides, photographic slides, in the lecturing of—in art history courses that we all took as undergraduates, and even in some cases as graduate students, I suppose, in which we had two images on the wall. And there was a point of the selection of the two to show some comparison or some difference between them, something that—some indication that there were some similarities or differences. The sense that one—pedagogically, one learned art history by looking at two images in comparison. Is that—that’s at least the way it was in the United States and in the United Kingdom. Is that the way it was in Germany as well, that actually this book layout had a kinda influence in how one lectured to students or how students learned from lectures?

GRASSKAMP: It’s an interesting question, but I think it’s—we cannot really answer it. It’s inter—they interfere. They’re two starting points for a new reception of art. The one is that you can buy a second projector for slides, and the—and the other is that you can print illustrated books and bind them. I find it very interesting that one of the possible models for Vigneau’s Encyclopédie photographique de l’art possibly was this series of reproductions that was published as The Museum in Germany in the 1890s, starting. But they did not make a bound volume, but they sold solitary plates. The principle was to print plates on a high—very high standard and sell them as single sheets, and collectible single sheets, and then give commentaries as a kind of installment. This is the 1890s. It was—the decisive development was that it was—it became cheaper to reproduce black and white photographs on paper that could be used in books, that would not be too thick and not too heavy, and so the paper would be thin enough to be bound to volumes. And this is the birth of the album as a double spread reproduction, while before, obviously, it was easier to have them as single sheets and plates and sell them that way.

I’m not sure if that influenced each other because the production spheres are too distant. I think that a lot of innovation in the publishing of books was made on the spot in the offices, in the—in the studios, without any contact or too much contact to what was done in the—in the lecture halls and in the seminaries [read: seminars]. We made a conference about Fritz Burger, which was one of my predecessors in the academy. And when he began to teach in 1912, he just ordered one slide projector. And I think when Wölfflin ordered his second one, this was a revolution, but it did not spread immediately over the place.

GAEHTGENS: But Walter, I think that Malraux knew Wölfflin’s Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe. And the book itself and the idea of the book is of course the basis of comparison. So I don’t think either that there is a direct relationship to—from this book to his later album. But the idea of comparison was in the air. And that inspired of course many, many people. Although I have to—also to say, when I studied in Paris in the 1960s in the lectures of the French professors, there was only one slide. No comparison.

CUNO: You make mention, Walter, that Malraux, of course, titled his book or his album, Le Musée imaginaire, The Imaginary Museum, and that there was the—that Vigneau’s encyclopedia of art was referred to by the author of its afterward as “an entire museum in one’s home.” That the effect of the—of the way that these comparisons are made can—you contextualize that in world art in colonial terms. This was also something that was a critique of contemporary museum culture as well, that in their concept of displays that Western museums colonized foreign cultures and subject them to a kind of intellectual colonialism, according to modern European aesthetic standards. So is there a common critique that could be applied to both the book projects and the modern museum project in decontextualizing these different works of art and making them seem as if there could be simplistic similarities between them when there’s no substantial similarity that exists?

GRASSKAMP: Let me tell you, I was not happy that—when I found out that I had to deal with this theme as well. [chuckles] When I started to make the journey through this room in which Malraux stands with the leaves with the double spreads of this book, I thought this would be a journey around a room, it would be a discussion of ways of reproducing art, of combing art, of publishing art. It would have been an essay I would have been completely content with. But then I saw some of his other sources. For instance the publication of Phaedon in Vienna as well as in London, which he certainly knew as well as Wölfflin. If he knows Wol—if—Thomas, I’m not sure if he knew Wölfflin. Claudia Bahmer, who wrote on Malraux, tried to find out in his library, what was there, what he had read, and when he bought it and in which edition he bought it. And it turned out Malraux wasn’t much of a reader. But of course, he was professionally interested in what other publishing houses were doing, so he must have sifted through hundreds and thousands of books. Not only to find the photographs that he would combine for his own purposes, but also to see what are they doing. Because this was a market that was expanding and each book was like a test, what the public would buy and what they wouldn’t. And so he certainly was one of the best-informed persons about what other publishing houses were doing.

But back to the question, Jim, that you posed. I was not very happy when I discovered I had to deal with the theme of globalization of art, of the universal character of art, which Malraux was very fond of, because I think that the discussion of and the history of this discussion is not yet ready to be quoted or cited or to really give a foundation. But of course it was inevitable to deal with it because most of the material that he worked with came from the Louvre, as well as the material that Vigneau worked with came from the Louvre, but with a decisive difference. The material that Vigneau worked with came from the Mediterranean; the material that Malraux worked with came from the Louvre as a result of colonial exchange between France and the colonies.

And so the horizon broadened. And I think this was politically delicate. But in retrospect, we should not over-emphasize this point, because in the horizon of their time, it was progressive what they were doing because they gave importance to images by baptizing them as art, that before had no importance at all—as for instance, as they said at the time, the “native” culture and the “native” art of Africa. It was a valuation. They gave value to things by calling them “art” and publishing them in art books in context with European pieces that made—that gave a new perspective, although the foundations of that—and the Louvre is a colonialist museum in this respect, the foundation of them was based on imperialism.

But this reminds [us] of Walter Benjamin’s dialectical remark that there is no piece of culture that is not also a piece of barbarism. And so I think we have to judge them in the horizon of their times. Nowadays, it’s much more complicated. And that was one of the reasons that I wasn’t glad to have this theme as well in the book. But I had to face it. Nowadays, it’s much more complicated. It begins with the terminology in which you write about it. Do you call it “art” or do you call it “images”? Can you—can you as easily decontextualize it as they did when they made these art albums? It’s a very complicated situation. But to give it a historical view, not only in text but also in illustrations, that was one of the aims that I had to fulfill.

CUNO: Let me ask you another question that might be related to this, and you can tell me if you think it is. Near the end of the book, you introduce the idea and the meaning of the imaginary museum. And that is that you point out that in the roots in Latin, imaginaire meant relating to images, and that in modern French, it means dreamed up, not real, fictive, false. And that in Malraux’s usage, that it was posed somewhere between image and imagination, between the pictorial and the fanciful. Tell us more about that. Because partly, what you’ve been describing with regard to other cultures is imagining a relationship that might not in fact exist, but that has been ultimately, ironically perhaps liberating in some respects.

GRASSKAMP: [chuckles] Besides being a politician, an adventurer, and a soldier, he was a poet. And I think most of his writings are poetic even if he thought them art historical. And so every notion that he uses certainly has double or triple meanings. And he loved this game with the we—meanings of words, not only in his novels and his—but also in his art historical writings. And if you would do a philological study Malraux’s use of the term “imaginary” you would see that over forty years of his publishing, it changes from a good marketing slogan, a good idea in the beginning, that foc—that gave the reproduction, the art album, a kind of metaphor, to the late Malraux, who is fascinated by the possibilities that images foster imagination, and imagination kind of re-fosters what you can do with images. That is what he’s playing with in his photographies as well. Or the photographies that he has made for his book. But it’s difficult to find a thread to follow in his use of the word “imaginary.” I think he loved the openness of his notions much more than the precision.

CUNO: [chuckles] Okay. Thomas, let me give you the last word on Walter’s important book. The Getty is publishing it because it relates directly to the Getty Research Institute’s interest in the historiography of art history and the history of museum culture. What are your final thoughts on the contributions of Walter’s book with regard to your project?

GAEHTGENS: Well, this is a complicated question. The—there are so many aspects in Walter’s book that are really inspiring. We are very much interested not only in the history of art but also in the history of museums. Museums have their history of collecting. In most cases, they cannot present the history of world art. That is impossible. Some by their history embrace an almost encyclopedic collection. However, museums are always incomplete, and the collections are displayed by geography.

This is, in a certain way, what Malraux wanted to overcome. He reached out with ambition to transfer the idea that art is universal. The media he developed, and in a certain way improved to perfection in his view were these albums of photography, which Walter has interpreted in such a fabulous and convincing way. Photography allowed to bring the examples of the creativity of mankind, wherever they came from, together. The medium [of] photography, in his view, was able to educate and to, in a certain way, transfer the beauty of art from all over the world. This is the imaginary museum, in my view. The legacy of Malraux is also that the encyclopedic museum is extremely important, in a certain way, in our global society. But this is only one way to go. You need photography and the albums and other ways to demonstrate importance of beauty all over the world.

CUNO: Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and SoundCloud or visit getty.edu/podcasts for more resources. Thanks for listening.

JIM CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

WALTER GRASSKAMP: He discovered that on two pages of a book, you have the possibility of compari...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

There are lots of mistakes in this podcast. For example, Malraux was NEVER an “art historian” and never sought to be. He was an art THEORIST. If you actually read his books on art, you will see that he specifically denies that they art histories. Many of the comments on Malraux’s life in the podcast are also dubious. What a pity that even new books on Malraux in 2017 are rehashing badly researched stuff like this.

Thanks, Mrs. Arthur L Keith III The view of Andre Malraux and examination of his work and perspective was quite insightful, learning a few gleams of the period in which the writer worked – helpful to a amateur artist.