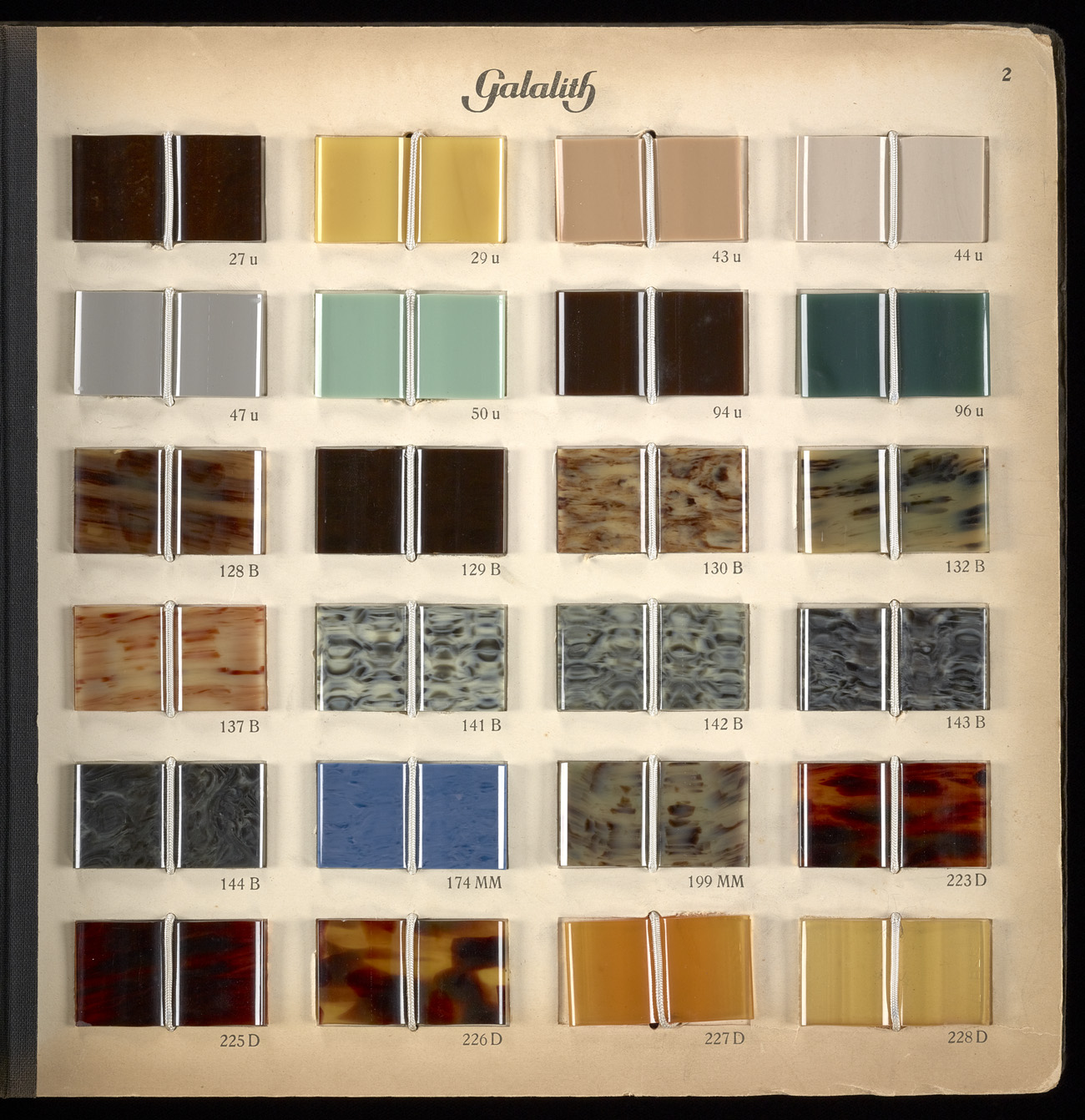

This trade sample book, created in the 1920s by Internationale Galalith Gesellschaft Hoff & Co., contains the product galalith, a synthetic plastic made of formaldehyde and casein, first developed in the late nineteenth century as part of an effort to create a new “dustless” chalkboard material.

The name galalith comes from the ancient Greek for “milk stone,” a reference to the fact that its major ingredient, casein, is a protein commonly found in milk (and a major component of cheese). While the modern Age of Plastics was ushered in by the development of industrial chemistry in the nineteenth century, producing many new kinds of synthetic materials—including other cheap plastics like Bakelite, celluloid, and Lucite alongside new pigments like aniline coal tar dyes—its basis is as old as civilization.

Lidded Pyxis, AD 1–100, unknown, Roman. Glass, 2 × 2 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.256. This small container from the Getty Villa provides a striking comparison: swirls of colored glass in this ancient Roman vessel imitate the variegated hues of agate, a much more expensive material.

The intriguing brilliance and translucence of galalith was inspired by another common material: glass. Used in the ancient world as we use plastic today, glass could be molded and blown into a panoply of different shapes, and mixed with pigments to imitate precious stones and gems, such as emeralds, chalcedony, pearls, and even gold.

While galalith was ultimately unsuitable for its original purpose, it was capable of being drilled, embossed, and cut, and became a go-to material for various odds and ends of everyday life, from glasses frames, buttons, and piano keys to combs, barrettes, and compact mirrors. It also became an excellent substitute for expensive materials like horn, pearl, and ivory—and was able to take on all the colors of the rainbow.

Galalith (“Milk Stone”) sample book, milk protein, formaldehyde, and pigments in Galalith (Harburg-Wilhelmsburg, ca. 1920), plate 2. Getty Research Institute, 2990-802

One of the first designers to see the potential of galalith for jewelry was the French merchant Auguste Bonaz, who began creating brooches made of the new material inspired by the Bauhaus style in the early 1920s. This trend eventually caught fire when, in 1926, Coco Chanel published a picture of the now-iconic little black dress in Vogue magazine and accessorized it with costume jewelry made of galalith. The German designer Jakob Bengel elevated costume jewelry and other plastics from fake to chic with his creative, sensitive products and a high level of workmanship. High fashion was made available to the growing middle class, who might not be able to afford real gemstones, but could afford galalith.

Galalith (“Milk Stone”) sample book, milk protein, formaldehyde, and pigments in Galalith (Harburg-Wilhelmsburg, ca. 1920), plate 3. Getty Research Institute, 2990-802

The urge to replicate the artistry of nature (for pennies on the dollar) has dominated artistic culture since antiquity, and is still alive today. The goals of the earliest alchemists have been realized in our new synthetic world, where we have discovered how to harness the chemical bonds of nature to create what we need in the laboratory.

_______

Seven plates from Galalith are included in the exhibition The Art of Alchemy at the Getty Research Institute (October 11, 2016–February 12, 2017).

The Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena has two early paintings with a small brown and white dog in them. I didn’t write down the information (Sorry!), but I remembered the dogs.

Why is the comment section in pale, pale, PALE, nearly unreadable gray? — Bjo