Staff conserve a tapestry at the Mobilier National. Photo courtesy of the Gobelins Manufactory

In early modern Europe, tapestries were the ultimate expression of princely status and taste. Costly in time, money, and talent, they were designed by the most famous artists of the day and meticulously woven by hand from wool, silk, and threads of precious metals.

Louis XIV built the French royal tapestry collection to dizzying heights, amassing over 2,600 examples—a story told in the exhibition Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV, which evokes the splendor of the Sun King’s once-great collection.

Made of natural fibers, tapestries naturally attract dust and dirt as they age. In preparation for the exhibition, the Getty–with generous support from the Hearst Foundations, Eric and Nancy Garen, and the Ernest Lieblich Foundation–sponsored the cleaning and conservation of two tapestries, The Entry of Alexander into Babylon (shown below after conservation) and the Chateau of Monceau / Month of December, which are now on loan from the Mobilier National in Paris.

Totaling over 700 square feet combined, the two monumental hangings were sent for cleaning to the De Wit Royal Manufacturers of Tapestry, a 125-year-old laboratory in Mechelen, Belgium, that cleans nearly all of the tapestries of the Mobilier National before conservation treatment.

The Entry of Alexander into Babylon, about 1665–probably by 1676, made at the Royal Factory of Furniture to the Crown at the Gobelins Manufactory. Design by Charles Le Brun; cartoon for the vertical-warp loom by Henri Testelin; weaving by Jean Jans the Elder, Jean Jans the Younger, or Jean Lefebvre. Wool, silk, gilt metal- and silver-wrapped thread, 194 7/8 x 318 7/8 in. Le Mobilier National. Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis

Cleaning by Vapor

At De Wit, the two tapestries were cleaned using the “aerosol-suction” method, which takes about six hours per piece. It works like this:

- The tapestry is laid flat on a suction table measuring 5 meters wide and 8.75 meters long and covered with a stainless steel mesh screen to support all the fibers.

- A cloud of steam containing a very small amount of detergent is produced above the tapestry. The steam humidifies the fibers and is sucked through the entire textile.

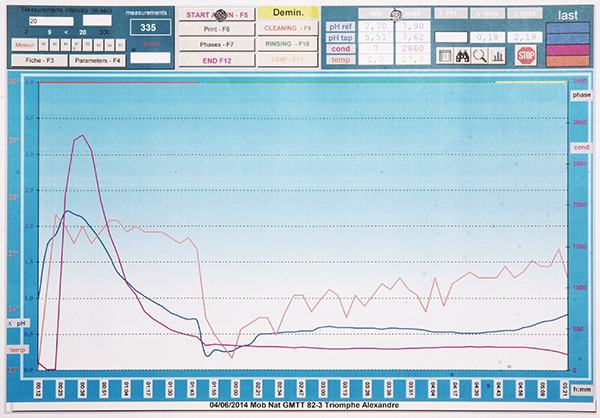

- Tapestry specialists monitor the temperature, the pH, and the conductivity of the water extracted from the tapestry throughout, and use a video camera with macro zoom to get a very close view of the evolution of the cleaning process.

A tapestry from the collection of the Mobilier National is cleaned at the De Wit Royal Manufacturers of Tapestry sits a suction table to be cleaned via a cloud of steam. Photo courtesy of De Wit Royal Manufacturers of Tapestry

This aerosol-suction process is a safe and high-tech way to clean tapestries. The constant suction helps stop dyes from bleeding and keeps the fabric still, preventing it from shrinking or warping and accomplishing very efficient cleaning without any possible re-deposition of the dirt. And the chemical and visual monitoring allows the process be closely controlled from start to finish.

Data from the cleaning of the tapestry The Triumph of Alexander showing the scientific monitoring of temperature, pH, and water conductivity during the cleaning process. Photo courtesy of De Wit Royal Manufacturers of Tapestry

Conservation and Display

Once the cleaning was done, Mobilier National staff performed conservation work on the two tapestries in order to preserve them for the future. Even with several conservators working side-by-side, the work took more than nine months.

Weavers conserve a tapestry at the Gobelins Manufactory. Photo courtesy of the Gobelins Manufactory

Conservators realigned undyed warp threads as needed and stabilized any loose colorful weft threads by stitching them to the warps. In some areas, threads were missing altogether. In these cases, conservators researched the original patterns and colors, then added threads in colors matching the surrounding areas. In some cases, they reinforced weak areas by adding cotton patches to the back (wall) side.

Once all this was complete, the tapestries were lined and fitted with a hanging strap—ready for their star appearance in Los Angeles.

Installation view of one gallery of Woven Gold at the Getty. Tapestries shown: The Entry of Alexander into Babylon, about 1665, probably by 1676 (Le Mobilier National); The Battle of Arbela, about 1670–76/1677 (Le Mobilier National); The Queens of Persia at the Feet of Alexander, about 1664, probably by 1670 (Le Mobilier National)

Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV was organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum in association with the Mobilier National et les Manufactures Nationales des Gobelins, de Beauvais et de la Savonnerie. The exhibition is on view through May 1, 2016; admission is free.

A longer version of this article originally appeared in The Getty magazine.

Bravo and thank you for this beautiful documentary !!!

Very interesting.

Impresionante !! Que trabajo tan preciso y apasionante. Gracias por compartir y conservar todo este fantastico patrimonio para las generaciones futuras.

Thank you for the article as I was searching how to clean the tapestry that i just purchased at auction.

XIX C. Aubusson tapestry. I do not have vacuum table but it gives some ideas how to clean it with controlled steam.

I will be happy for any suggestions.