Cover of Artists’ Cookbook, 1977, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 1977 The Museum of Modern Art

“When I make a show it’s like when you arrive at home and you open your fridge at night and there’s two potatoes and one sausage and two eggs, and with all that you make something to eat. I try to make something with what is in my ‘fridge’.”

—Christian Boltanski

In the 1977 ring-bound volume The Museum of Modern Art Artists’ Cookbook, the very first entry just happens to be a chronicle of Op-artist Richard Anuszkiewicz’s gusto for salad. Next to a photograph of the artist tossing a pile of greens in his New York kitchen, the editors, Madeleine Conway and Nancy Kirk, offer the following commentary: “Richard treats his lettuce carefully, washing, drying, and refrigerating it for extra crispness. He adds the dressing at the last minute to prevent a watery taste. Along with the greens, Richard uses whatever is at hand, especially cold cuts and cheeses.”

Anuszkiewicz’s “salad” recipe, in which cubed cheese far outweighs lettuce, is anomalously unhealthy in a book filled with talk of diets, calories, and seasonal eating. Screeds against junk food and paeans to organically grown food make Artists’ Cookbook feel contemporary—although the single mention of arugula, italicized and sporting its Italian spelling (“arugola”), charmingly dates it. With some careful adjustments and substitutions, one could attempt signature dishes that once graced the tables of Christo or Romare Bearden—I, for one, plan on trying Alex Katz’s family recipe for “remnant pie,” consisting of a week’s leftovers stuffed between flaky layers of dough. But on the whole, we might gain more from treating the book as an incisive historical artifact, a rich anecdotal snapshot of bohemian late-1970s New York (and its well-to-do suburbs) captured through colorful accounts of what the city’s artists were putting on their stoves and into their mouths.

It isn’t surprising that hints of misogyny creep in—the discourse around food, after all, tends to be gendered. Robert Motherwell offers a particularly egregious example with his declaration that his wife “is a born cook, better than I am in execution, as most European women are—such devoted care and discretion! But I think men are usually better menu makers, of what goes with or contrasts with what.” (The same prejudice has been invoked recently to explain why men still dominate the field of top international chefs.)

Enter Alice Neel, who offers a much-needed palate cleanser a few pages later, recalling, “I worked with Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline on the WPA in the 1930s, but I never cooked for them. Oh no. I wanted to have a man who would cook for me.” Neel, who once traded a painting for caviar, also notes nonchalantly that she only eats eggs “where no rooster ever ruined the hen—because they’re better for you.”

Alice Neel in the kitchen. Originally published in Artists’ Cookbook, 1977, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 1977 The Museum of Modern Art

Other historical tidbits are innocuous but revealing. Many contributors gushed to the editors about their revelatory early experiences of Parisian food, betraying their status, in retrospect, as the last generation to enjoy a de rigueur coming-of-age in Paris. I can only imagine what sort of recollections will populate such a cookbook twenty years from now, when today’s young artists have reached mid-career and look back on days spent eating bibimbap during residencies in Korea (or Los Angeles, for that matter), or scarfing currywurst and doner kebab in the wee hours of the night in Berlin. (Whether those culinary achievements will inspire the same platitudes as French patisserie, we can only hope.)

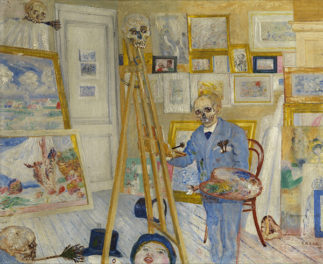

MoMA’s Artists’ Cookbook is an early example of an ever-growing sub-sub-genre of cookbook-cum-art book, or vice versa. It was preceded by The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook, published in 1954, which featured a recipe for hashish fudge that became instantly infamous, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s The Art of Cuisine, published in English in 1966, with Toulouse-Lautrec’s charming illustrations gracing nearly every page. Since then, we’ve seen cookbooks from the kitchens of Georgia O’Keefe, Jackson Pollock, Salvador Dali, and even Joseph Beuys, whose recipe for “Drakeplatz Stew,” named after the address of his studio in Düsseldorf, calls for alternating layers of cabbage, onions, and ground meat, but notes that “you can let your imagination guide you.” (Another recipe for salt cod is less forgiving, demanding that the chef soak the fish in running water for two weeks. Not recommended in drought-stricken California.)

My favorite forays into the genre are perhaps the most fanciful. Ryan Gander’s Artists’ Cocktails, which catalogues drinks consumed during the run of his Absolut-sponsored bar installation at Documenta 13, is the only book I’ve seen to include a lengthy disclaimer. “The recipes in this book should be considered as a series of artworks. For this reason the authors and publishers will in no way be held responsible for any consequences in relation to the realisation of the recipes. The cocktails in this book”—which range from Liam Gillick’s glassful of vodka to Pierre Bismuth’s MSG-soaked Excitatory Neurotransmitter Cocktail—“should only be interpreted by a competent, well-adjusted adult, with an impeccable moral compass.” Mixologists and drinkers beware.

Unsurprisingly, art and cooking have also found one another on the Internet, where one can still find the video that appeared on the website of The Wall Street Journal around the time of Marina Abramović’s 2012 MoMA retrospective, documenting an encounter between Abramović and actor/writer/artist James Franco. I won’t give it all away, but it suffices to say that Abramović prepares a special treat for Franco and he eats it ceremonially. It will make you uncomfortable; you might feel compelled to watch it twice. On the more palatable end of the spectrum is the tumblr Starving Artist, the brainchild of Sara Zin, who landed a book deal to publish her “illustrated cookblog” with recipes for asparagus and eggs, galettes, and chocolate raspberry birthday cake, each coupled with a lusciously detailed watercolor reminiscent of the drawings that grace the back of Cook’s Illustrated. It’s a predictable but also undeniably appealing “slow food” answer to the Instagram culture of food porn, which is as quickly consumed as it is produced. You won’t want to swipe through Zin’s watercolors at a breakneck clip; you’ll savor them, slowly, as you would a soul-satisfying plate of really good food.

Text of this post © Andrea Gyorody. All rights reserved.

Comments on this post are now closed.