On August 27 at the Getty Villa, dance artist taisha paggett and sound artist Yann Novak presented their collaborative work “Mountain, Fire, Holding Still.” Part of the Getty Museum’s ongoing project that invites contemporary artists to respond to the collections and sites through research and interactive programs, this daylong, site-specific performance and sound installation in the Outer Peristyle invited viewers to meditate on our experience of race, time, and the body as a vigil spanning antiquity to today. In this interview, they shared with me insights into their creative process for developing the program.

Audrey Chan: Could you each describe your practice and values as artists?

Yann Novak: I think of myself as a sound and visual artist. My work is rooted in experience, so I use sound, light, and projection to focus awareness on the present moment. I like how sound and dance communicate experience and transcend written and spoken language.

The jumping-off point for my work is the transition from hearing to listening. Hearing is passive: it’s not an active process. When you’re listening, you are actively gathering. I find that transition to be the place that I’m most interested in exploring because it’s a shift in consciousness.

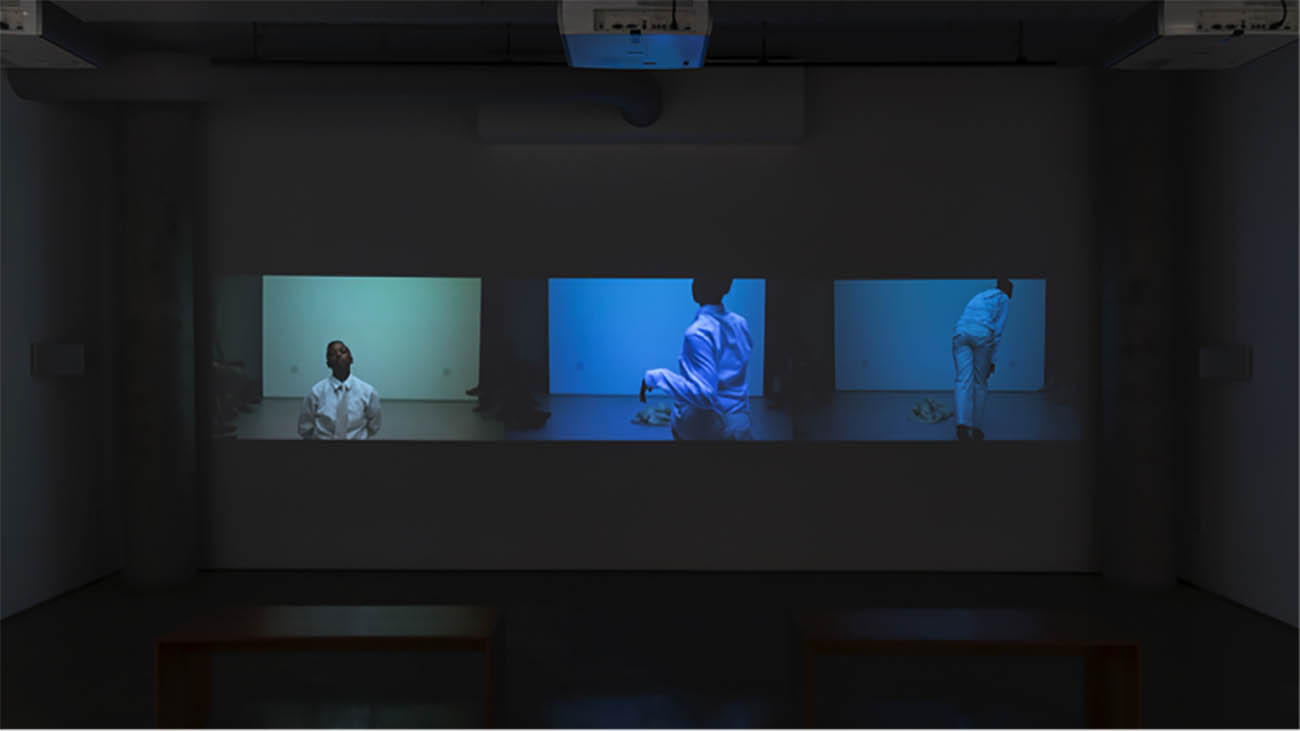

taisha paggett and Yann Novak, Composite Fields, 2015. Cinematography by Ashley Hunt. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy of the Doris McCarthy Gallery

taisha paggett: Yann and I have a shared interest in the experience of the performance, in bringing people together and making that togetherness more substantial by getting one’s sense of time and space to shift. A lot of that is in slowing down time, stretching out time. What frames my work is this sense of how the performer and the audience can simultaneously contribute to a shared experience. The experience of a performance for me is more important than the details of what actions my body does.

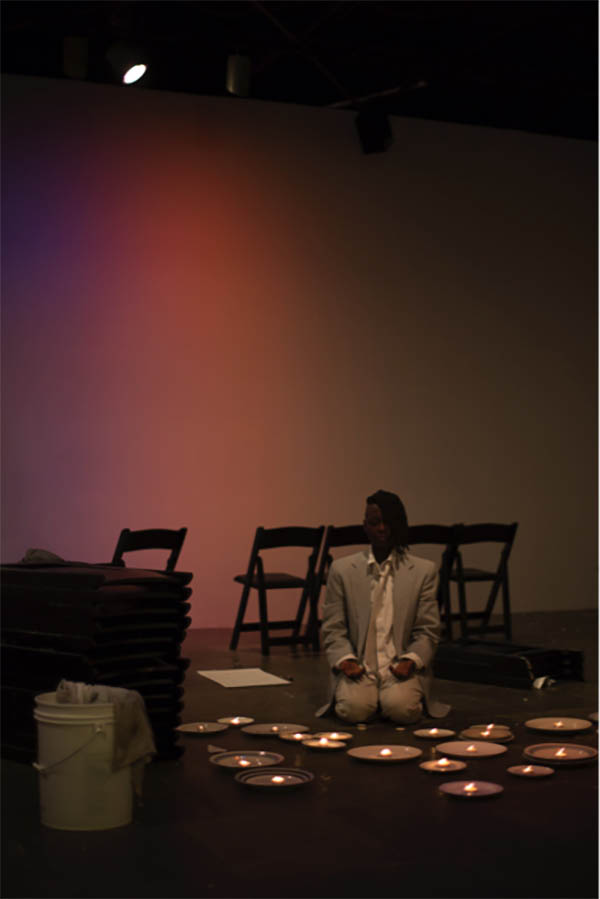

taisha paggett performing Underwaters, (we is ready, we is ready) at the 2014 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Christopher Golden

Novak: It’s about creating a situation for an experience to happen. We’re also not delegating what the valid experience is.

paggett: I think we spend the majority of our lives inside of question marks. In general, we’re constantly filling in the blanks of what we don’t understand, and we do that at such a rapid rate that it’s impossible to distinguish what we’re trying to understand from that which we understand already. There’s something political about bringing people together to create contemplative spaces, particularly in this time in which desire to share and produce and be a part of public space intersect with a new reality, the fear of flying bullets, the fear of becoming another victim of public violence. There’s something important about the slowing down and the parsing apart, creating space for this perpetual tenuous state.

Chan: Tell me about your current collaboration at the Getty Villa, “Mountain, Fire, Holding Still.”

paggett: I’ve been thinking about what it means to be a body on display in this presentational space of the museum, where it’s a different type of extended looking. There’s something about being present and also concealed in sight that’s interesting.

Novak: We’re also in an interesting moment to be thinking about those things in time and not just [at] the Getty, but how bodies, how people as bodies move through space. It’s changing drastically year by year right now.

taisha paggett and WXPT (Joy Angela Anderson, Charmaine Bee, Fonzy Cervera, Heyward Bracey, Rebecca Bruno, Erin Christovale, Loren Fenton, Maria Garcia, Kloii “Hummingbird” Hollis, Meena Murugesan, taisha paggett, Sebastian Peters-Lazaro, Kristianne Salcines, Ché Ture, Devika Wickremesinghe, Jas Wade, and Suné Woods), evereachmore, 2015. Commissioned by Clockshop for the Bowtie Parcel at The LA River. Photo: Ashley Hunt

Chan: What informed your decision to have the performance span morning to night?

paggett: Time is material and space is material. I was interested in a time frame that allowed one to experience a shift of the day, to feel the day move—just to know that. We are very familiar with what five minutes feels like, but what does it mean to feel 10 hours?

Novak: One of the things I really love about durational work is that you’re giving the audience agency to direct when the performance begins and ends for their own experience, so one person can watch for five minutes and another person can watch for three hours, and both of them are valid experiences. It allows us the opportunity of discovery; it can be stumbled upon.

paggett: There’s always something of interest for me in territorializing space, and occupying a performance longer than it’s meant to go on. And also thinking of performance itself as a kind of research, my own interest in what happens over time, how do I experience time.

Novak: I always want my sound work to be experienced [as] like a really beautiful air conditioner. In technical terms, there’s the “attack” and “decay” of sound. The “attack” is how the sound comes into being. “Decay” is how it dissipates back into silence. I never want to work with either of those aspects; it’s all about the “sustain” in between the two.

Chan: taisha, how do you approach the Outer Peristyle as a performance site for movement? The architecture is very geometric with a manicured garden. It’s designed for a wealthy villa owner to walk with a guest while musing on subjects like philosophy, politics, and literature, as a means of displaying his status. How do you make space in an environment that’s already replete with decoration?

The Outer Peristyle Garden at the Getty Villa

paggett: The space conjures up this type of reverence and grandness. I’m going back to an earlier idea of layered silhouettes of bodies and how black is a type of layering that creates a void or saturation of all color. I began thinking of what other materials exist and disappear, and are covered over time, that exist across the body. I will be developing the physical aspects of the performance through a research and rehearsal process with Marbles Jumbo Radio, who is based in the Bay Area and lives in an environment that is very rural and woodsy. We’re going to be feeding material to each other through our different processes and what will be interesting will be seeing how our two worlds and different relationships to space connect in the Getty.

Chan: You’ve been thinking about the performance as a vigil, a meditation on the recent succession of human tragedies in the U.S. and globally.

paggett: I’m interested in gathering movement material and structuring it with the thought of a vigil. I feel sensitive to questions—not just of artists’ responsibility—but of how we are in dialogue with what’s happening and how we are an interface for people coming from elsewhere, coming from different perspectives, And what are we not saying and how is that not saying a type of permission or avoidance? In all that, I think what came up for me is that what we are needing is a space of reflection.

Novak: At the Getty Villa, these layers kept opening up. The [replica] bronze statues in the gardens already felt like a vigil for the people who died [when Mount Vesuvius erupted] because the grey patina replicates the effect of the ash rather than what the bronzes would have originally looked like. Now we’re overlaying a vigil for the people who have fallen in our contemporary world.

Bronze sculpture of a praying woman in the Getty Villa’s Outer Peristyle.

We questioned ourselves in this time and moment, asking how do we even create something aesthetic? How can I want to create a beautiful sound environment in such an ugly time? What does it mean to do that? Bodily movement, dance, is to me—even when it tries to be as ugly as possible—it’s still beautiful to me. Both of us work in these mediums where we’re constantly having to push up against an inherent aesthetic quality to the work. How do we deal with that in such heavy times?

We were talking in the galleries about how beauty was often utilized in objects for people to be buried with, or the things that they would take with them. We’re going to make a piece that these fallen can take on to the next life. A vigil is as much for them as it is for us.

paggett: With all this said, I also feel that it’s important to say that the vigil is a very ambivalent gesture. All these people are dying and we’re just going to commemorate it? It’s less “this is how we solve it” but more of a “what else is there to do”? It feels like a compromise, a placeholder, and I think the idea is to think of a vigil as “being with” but also where questions are still being generated, especially as we’re standing inside of this.

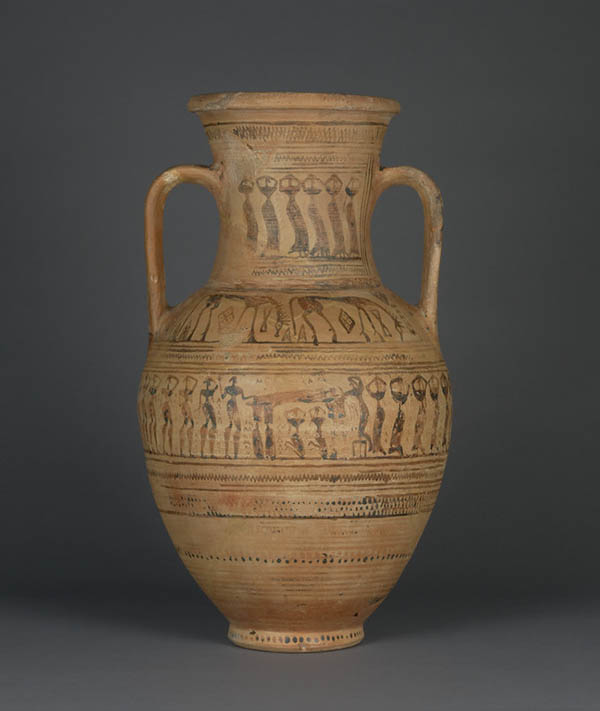

Chan: Many of the objects that have survived antiquity were used in funerary ritual to commemorate the dead, typically for the social elite. There is a Greek archaic vase in the galleries that depicts a funeral procession with mourners. There’s also a sarcophagus depicting Dionysian revelry that is identified as being for a child because of its small size. It shows how the process of grieving could be represented in a visual way and it implies all the sounds that would accompany it, like the wailing of the mourners, the cymbals and the reed instruments of the Dionysian rites. In both cases, there is a catharsis in the physical expression of grief.

Storage Jar with a Funerary Scene, 710-700 B.C., attributed to the Painter of Paris CA 3283. Terracotta, 17 3/4 × 9 5/16 × 9 11/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, VL.2010.22. Rabin Collection

Sarcophagus with Scenes of Bacchus, 210-220, Roman. Marble. J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.AA.275

paggett: We revert to things of beauty because they give us . . . this space [of the museum] is so much about beauty and this type of aesthetic that we’ve come to valorize. I’m thinking about the drapery [of ancient Greco-Roman garments] as the symbol of a certain opulence, but also of an impossibility—the tenuousness of holding and having for oneself all of that fabric. Inside the postures of robed statues and sculptures is the effort of power . . .

Left: Statuette of a Woman, about 460-450 B.C., Greek. Bronze, 6 5/16 × 1 3/4 × 1 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 96.AB.47; Right: Wreath with detached stem including leaves and detached berries, 300-100 B.C., Greek. Gold. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 92.AM.89

Chan: That’s something that your costume designer, Gregory Barnett, is going to be thinking about a lot. What inspired you to have a costume element to your piece?

paggett: Greg comes out of the form of burlesque and a type of performance that is very much about the adornment of the body. My typical contexts are very much about the muted and minimalist elemental body, white lights and streamlined silhouette on a bare stage. Greg has always been interested in ornamentation, and his sensibility felt like a good match for this piece at the Villa.

Chan: I see your project as making space. But the Getty Villa, which was based on the architecture of the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum, is a far cry from a minimalist “white cube” space. You’re re-characterizing what this space can be, making the Outer Peristyle a porous and communal gathering space and allowing it to perform with you over the course of a day.

paggett: The site itself is already so full … I see myself more like a shadow in the space, where moving or action happens as a result of, or in dialogue with, the passing of time. Time is what I have to grapple with, what I have to sit beside, to mourn, and to perhaps make feel expansiveness again. I’m thinking of time here as a chronological marker and also as a type of material, which, being invisible, returns me to thinking about absence, translation, loss … Time feels so synonymous with death, perhaps because, these days, every moment you blink, another black life has been taken away. The work may be ephemeral and the performing body may be ephemeral, but you can say that from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. on August 27th, that conversation will occur. The holding of time and the action of making visible that which is perpetually made invisible, will be the substance.

______

“Mountain, Fire, Holding Still.” is a durational performance/installation by dance artist taisha paggett and sound artist Yann Novak created in collaboration with visual artist Gregory Barnett and movement artist Marbles Jumbo Radio. Presented in the Outer Peristyle of the Getty Villa, it is a meditation on death, labor and blackness in antiquity as it relates to the contemporary body, and a performance-as-vigil for past and future lives. The performance took place on Saturday, August 27, 2016 from 10 a.m.-8 p.m. in the Outer Peristyle of the Getty Villa.

Related Posts

Conveying Metaphor Through Costume

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks