Kelmscott Manor: In the Attics (No. 1), 1896, Frederick H. Evans. Platinum print, 6 1/8 x 7 15/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.444.89

When Samuel J. Wagstaff Jr. met Robert Mapplethorpe in 1972, he had a rather dismissive attitude toward photography. As Wagstaff’s relationship—as both a patron and lover—with the young artist developed, the former curator came to view photography as an underappreciated art form. He embarked on mission to become photography’s champion, making his first major purchase—twelve prints by the British photographer Frederick Evans—in 1973. Over the course of a decade, Wagstaff used his inherited wealth to assemble a collection of 26,754 photographic objects, all with the intent of raising the prominence of the medium.

The J. Paul Getty Museum acquired the entire collection in 1984, making it a foundational holding in the recently formed Department of Photographs. The current exhibition The Thrill of the Chase: The Wagstaff Collection of Photographs showcases a selection of the tastemaker’s collection, presenting artworks from the 1830s to late 20th century by both well-known and unknown masters.

In preparation of the exhibition catalogue, associate curator Paul Martineau answered questions from the book’s editor, Dinah Berland, on the significance of the collection, the aesthetic appetite of its patron, and some of its many visual highlights.

Dinah Berland: What makes the Wagstaff collection so important?

Paul Martineau: The Wagstaff collection is the largest single holding of art—in any medium—at the J. Paul Getty Museum. It spans from the experimental beginnings of the medium to the 1980s. The collection is renowned for the quality and depth of its holdings of rare works by nineteenth-century masters such as William Henry Fox Talbot, Hill & Adamson, Gustave Le Gray, Nadar, and Julia Margaret Cameron.

Mrs. Herbert Duckworth, 1867, Julia Margaret Cameron. Albumen silver print, 13 3/8 x 9 13/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.443.21

Did Wagstaff have a distinct method or purpose in acquiring new works?

The collection was assembled over the course of a decade, from 1973 through the first half of 1984. Photography was an undervalued art form and one that Wagstaff thought that he could have an impact on. Wagstaff collected photographs by recognized British, French, and American masters, as well as by unknown makers. He traveled to London and Paris regularly to attend auctions and often trolled secondhand shops and flea markets, returning home with shopping bags full of prints.

Collecting became an obsession and within a few years he was considered one of the preeminent collectors of photographs. Wagstaff enjoyed the attention he was getting and went a step further—he began to promote photography as fine art by exhibiting, publishing, and lecturing on his holdings.

How did you go about selecting the 147 works reproduced in the exhibition catalogue out of such a large field of images?

I selected the masterpieces first then added the more unusual objects and images—the daguerreotypes, the cartes-de-visite, the stereographs, the mug shot album, the medical photographs, and those by unknown makers. The blending of these works was essential to convey the unique character of the collection.

Dalí Atomicus, 1948, Philippe Halsman. Gelatin silver print, 10 3/4 x 13 9/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XP.727.12. © Halsman Archive

What was Wagstaff’s individual aesthetic as a collector, and how did it evolve over time?

Wagstaff was attracted to photographs that had the power to get his imagination going. For example, a photograph of a flooded street in Lyon by Louis Froissart (1856), a photograph of 18,000 soldiers in a formation that represents the Statue of Liberty by Mole & Thomas (1918), and a photograph of an elegant woman dressed in a satin ball gown and a mink stole entering a building through a revolving door by Robert Frank (1952) are all fodder for a mind eager to spin esoteric tales beyond the frame. His taste for the idiosyncratic—the images that surprised him because he had never seen them before—became more pronounced as his collection grew in size.

Wagstaff had an abiding interest in American history and was drawn to photographs of the Civil War, Native American people and their cultural traditions, and images of the American West that were made following the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. Another thread that runs through the collection is that of suffering and death. This can be felt in the chilling absence of people in Roger Fenton’s Crimean War battlefield, Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855), as well as in the shriveled blooms at the base of the stalk in Frederick H. Hollyer’s floral still life Lilies (1885).

The Great Wave, Sète, about 1857, Gustave Le Gray. Albumen silver print, 13 1/2 × 16 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.637.1

What do you consider to be among the most outstanding photographs or groups of photographs in the Wagstaff Collection?

Among the most outstanding photographs in the collection are those by Gustave Le Gray. His beech tree is stunning in its play of light and shadow, and his marines are exquisite examples of composite printing. Le Gray was a relative unknown when Wagstaff began purchasing his prints. Wagstaff marveled at how he could have been overlooked, saying, “It’s like leaving Rembrandt out of a history of Western art!”

Another category of outstanding works are those by unknown makers. These prove that Wagstaff had a great eye and had the courage to hold them up against works by established masters of the medium. For example, there is a sixth-plate daguerreotype portrait of a girl wearing a dress with a bateau neckline and triangular-shaped cap sleeves—her hands are folded over her forearms at her waist in the shape of an ourobos. Another is a dynamic photograph of two boxers in the ring—above them is an array of lights and below is a line of photographers with their cameras ready to capture the knock out. Both of these images are memorable in different ways despite the fact that their makers remain unknown.

What does the exhibition and catalogue tell us about the nature of collecting photographs? Did the Wagstaff Collection inspire the J. Paul Getty Museum to acquire other artworks by particular photographers?

Wagstaff taught us to look beyond the established canon to photographs by unknown makers or to those that were not created as art. Wagstaff once stated, “Beauty can be found in truth, or better still, in unexpected places.” This collection led the Department of Photographs to acquire bodies of work by a number of artists. Some of these were under the radar, so to speak, such as Jo Ann Callis, William Garnett, and Edmund Teske.

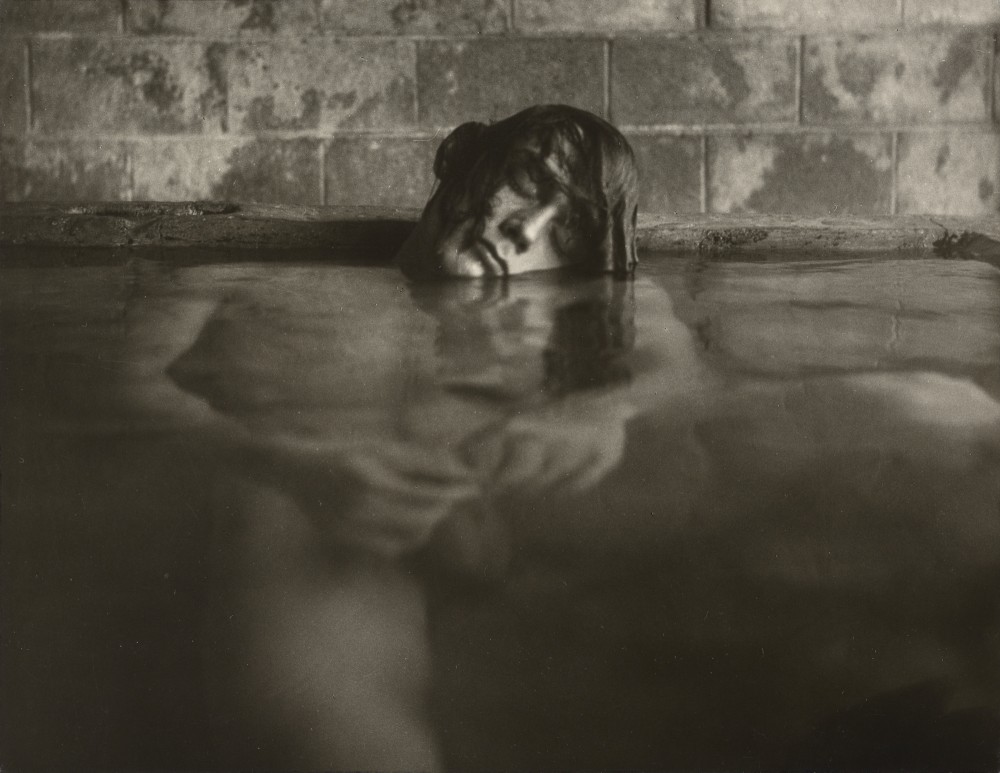

Mineral Baths, Big Sur, California, 1967, Edmund Teske. Gelatin silver print, 7 5/8 x 9 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.690.1. © Edmund Teske Archives/Laurence Bump and Nils Vidstrand, 2001

What might photography scholars and enthusiasts find in the overall collection that might be helpful or inspiring?

The collection—as represented in the exhibition catalogue—follows the thread of the history of photography in its many historic, aesthetic, and technical permutations from its birth in the 1830s to contemporary photographs created in the early 1980s. It also serves as complex portrait of the life, times, and taste of the man who assembled it.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.