A pair of Roman mosaics, first discovered over a hundred years ago in Southern France, have recently been reunited in the exhibition Roman Mosaics across the Empire at the Getty Villa. The mosaics originally decorated adjacent reception rooms in a Roman villa, and each one is now in the collection of a Los Angeles museum. Dares and Entellus resides at the J. Paul Getty Museum and Diana and Callisto is in the holdings of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

How and why did two mosaics from Southern France end up in Southern California?

Global Wars and Sugar Beets

The modern history of the mosaics begins in the 1830s. Strangely enough, their discovery was an inadvertent consequence of unrest in the Caribbean and the Napoleonic Wars. In the early 1800s, the Haitian revolution freed the colony Saint Dominique (modern Haiti) from French control. Meanwhile, Napoleon’s wars with everyone in Europe led to an extensive British Royal Navy blockade, restricting French trade with the West Indies and effectively cutting off France’s supply of sugar cane.

Without Saint Dominique or viable trade with the Caribbean, France had to look elsewhere for sugar. Napoleon, eager to strengthen the French economy and solve the sugar shortage, banned the importation of foreign sugar and, in 1811, financed domestic training programs for processing sugar beets, a relatively new technology. The French sugar beet industry was an immediate success; by the 1830s, there were over 500 new sugar mills in France.

The Marquis de Forbin-Janson, a wealthy landowner from Villelaure, eagerly jumped on the sugar beet bandwagon. In 1832, the marquis constructed a large sugar mill factory, Le Fabrique, and developed tracts of land for the new crop, which required very deep furrows for planting. In the spring of 1836, workers in an uncultivated field known as the Tuilière discovered an ancient Roman villa when their plows brought up large chunks of mosaics. The marquis’s steward, Monsieur Alique, had the site properly excavated, revealing four rooms with paved mosaic floors divided by an unpaved corridor.

Unfortunately, early reports of the mosaics do not describe their decoration. Despite appeals from Alique, the marquis had no interest in fully excavating the pavements. Alique reluctantly reburied the mosaics and their exact location was forgotten.

After 12 years of production, the Forbin-Janson sugar beet business ran into financial difficulties and ultimately failed, leaving the estate bankrupt. Upon the death of the marquis in 1848, the Forbin-Janson estate of over 3,000 acres—about five square miles—was sold at auction.

Newspaper clipping of the Forbin-Janson estate auction, October 1, 1848.

The 1836 discovery was not published at the time, but fortunately César Jacquème, a doctor from Marseille with an interest in local history, recorded the details years later. Jacquème first learned of the mosaics in 1866 while completing his medical residency in Paris. Coincidentally, Alique, the former steward of the marquis and a family friend of Jacquème, had moved to Paris after the dissolution of the Forbin-Janson estate.

Portrait of César Jacquème. Histoire de Cadenet. 1922. Reprint, Marseille: Lafitte Reprints, 1979.

Alique, homesick for Provence, would often visit Jacquème to reminisce. It was during one of these long evenings that Alique shared the story of his exciting discovery in the Tuilière field. Intrigued, Jacquème later followed up with friends in Villelaure; they reported back that sadly the mosaics had long since been destroyed—plowed up and lost.

Rediscovery and Popularity

Fast forward 30 years. The new owner of the Tuilière field, Monsieur Peyrusse, decided to develop the land as a vineyard. Soon enough, plows brought up small pieces of concrete with mosaic decoration. Unlike the marquis, Peyrusse was fascinated with this discovery and had the room carefully excavated. He later described the mosaic as a colorful scene filled with humans and animals.

Since it was the middle of winter, Peyrusse feared that frost and rain would damage the exposed mosaic, so the room was carefully reburied until excavations could resume in warmer weather. When the mosaic was re-excavated in the late summer of 1899, Peyrusse was horrified to discover that accidental plowing had destroyed the entire central scene. Excavations continued into the spring of 1900 and three other rooms were uncovered, all under just a few feet of earth.

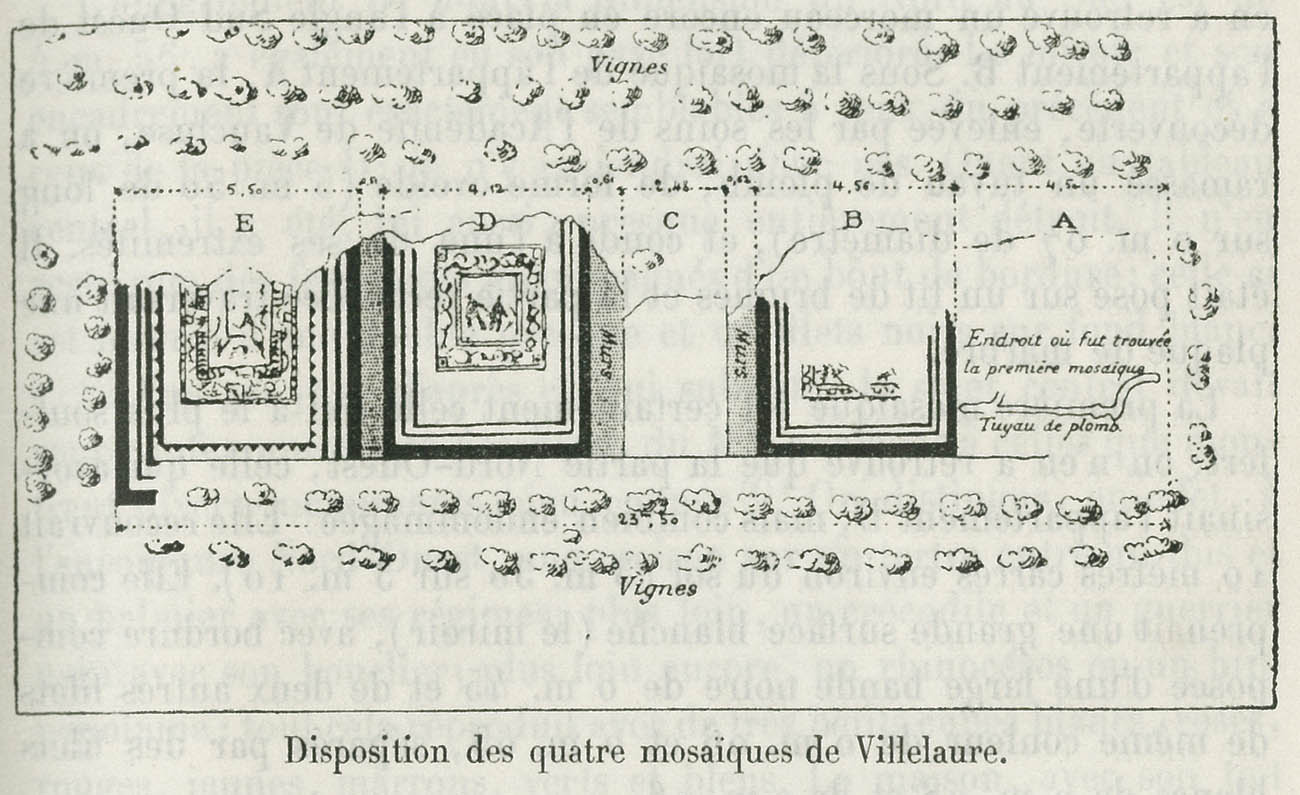

All four rooms shared the same decorative scheme—a colorful central panel surrounded by a white mosaic floor and a black-and-white border pattern along the walls. Like the first room, the second room’s central scene suffered extensive damage, with only a fragmentary corner depicting a Nile river scene preserved. The other two rooms contained the mosaics of Dares and Entellus, shown just after combat, and Diana and Callisto, surrounded by hunting scenes.

Peyrusse alerted French antiquities specialists of his discovery and the finds were carefully documented and published in an excavation report in 1903. The publication features a plan of the excavation and color watercolors of the three mosaics in situ before any restorations, and records other finds, including pottery, a piece of marble, and a lead pipe under the floor of the first room. The central panels of the mosaics were lifted and displayed on site. They quickly became quite the local tourist attraction.

Plan of the mosaics excavation (1903) by Henri Nodet. Originally published in H. Labande and Villefosse, “Les mosaïques romaines de Villelaure,” Bulletin Archéologique du Comite des Travaux historiques et scientifiques, p. 5.

Nile mosaic in situ, watercolor by Henri Nodet (1903). Originally published in H. Labande and Villefosse, “Les mosaïques romaines de Villelaure,” Bulletin Archéologique du Comite des Travaux historiques et scientifiques, plate 2. Reprinted in and scanned from Georges Lafaye, Inventaire des mosaïques de la Gaule et de l’Afrique, vol. 1, Narbonne et Aquitaine. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1909, no. 103.

Peyrusse advertised the mosaics in local newspapers and crowds of people came on Sundays to see the ancient artworks. Visitors were charged three sous (about three cents), though wealthier guests paid six, presumably for a less crowded view. Each night the mosaics were covered with straw and tarps; during the day, farmhands kept them damp with a humidifier to heighten the color contrast and create a glossy appearance.

A World War and Art Dealers

Peyrusse’s tourist attraction flourished, but in 1913, with war imminent, France expanded the draft and all of the young men, including the farmhands taking care of the mosaics, left for the barracks. The mosaics were stored in a nearby farm building until 1919. After the war, the French economy crashed and Peyrusse, likely on the brink of bankruptcy, sold his prized mosaics.

A few years later, the mosaics turned up in a small antiques shop owned by Frederick Rinck in Avignon. According to one anecdote, in 1920, the shop owner complained to a visitor, “See, these come from Villelaure; I’ve had these [mosaics] for years and they are in my way!” Rinck unburdened himself of the mosaics when they were purchased by R. Ancel, an antiquities dealer in Paris.

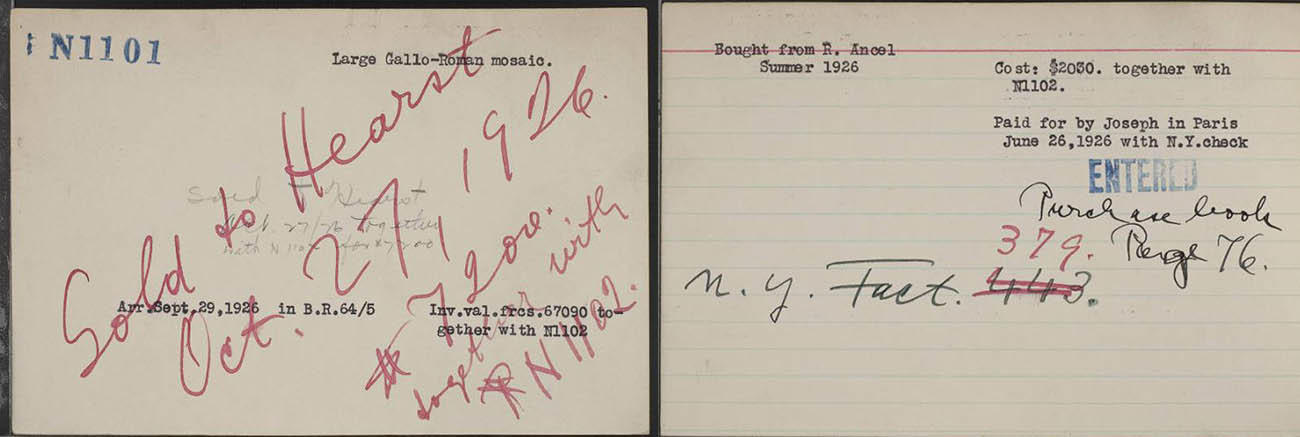

In 1923, Ancel offered the two mosaics to the Louvre and the antiquities curator Étienne Michon was eager to acquire them. (Ancel seems to have not acquired the fragmentary Nile mosaic. Peyrusse’s wife later claimed it had been left with the Musée Calvet in Avignon, but the museum’s records do not support this. Perhaps it ended up in a private collection, or, as is more likely, the mosaic was damaged, repurposed, and lost.) The museum, however, refused the purchase due to a lack of space, so Ancel sought out other buyers. Three years later in the late summer of 1926, Joseph Brummer, a famous art dealer, purchased the mosaics from Ancel and shipped them to his New York gallery. Within a month, Brummer had an American buyer, the newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst.

Brummer Gallery catalog card (l–r: front and back) for pair of mosaics purchased from R. Ancel for $2,030 on June 26, 1926, in Paris. The card notes the mosaics arrived in New York on September 29, 1926 and were sold as a pair to Hearst on October 27, 1926, for $7,200. Depending on the shipping costs, Brummer made a profit of around $5,000. Brummer Gallery Records N1101 and N1102.

Hearst, Getty, and the Hollywood Elite

Hearst bought the pair of mosaics during a period of energetic collecting. In the 1920s, the postwar art market was booming and Hearst needed material to furnish and decorate his six large residences. The Villelaure mosaics were sent directly to his unfinished hilltop estate in San Simeon, California.

A year later, Hearst purchased another Gallo-Roman mosaic from Brummer—an entire floor in 22 parts with a central scene of Orpheus surrounded by animals (which is also on display in Roman Mosaics across the Empire). This mosaic had been stored in Hearst’s New York warehouse in the Bronx. Financial difficulties in the late 1930s forced Hearst to liquidate assets, and, in 1941, he sold over half of the objects in his Bronx warehouse, including the Orpheus mosaic.

As Hearst’s fortunes were falling, those of a California businessman were rising. In 1949, 57-year-old J. Paul Getty purchased the Orpheus mosaic for his new ranch house in Malibu. Getty took great pride in the successful installation of the mosaic in his “Roman Room.”

The Orpheus mosaic installed in the Ranch House’s “Roman Room” (1950). Some of the border elements were cut down to fit the room, but the central panel remains intact. Photographer unknown. Source: J. Paul Getty Museum

Sometime after Hearst’s death in 1951, James N. Evans, the former chief guard at San Simeon, bought the Villelaure mosaics from the Hearst estate for a fraction of their original value. Phil Berg, a famous Hollywood talent agent (Clark Gable and Judy Garland were his clients) and an avid art collector, learned of Evans’ lucky acquisition and in 1962 bought the mosaic of Diana and Callisto. (According to Berg, it was Hearst’s son Randolph who alerted him to the mosaic. The connection between Berg and the younger Hearst is not entirely clear, but perhaps the Hearst family’s Hollywood connections played a part. Berg later donated over 200 objects, including the Diana and Callisto mosaic, to LACMA.)

Evans remained in possession of the Dares and Entellus mosaic until 1970, when he offered it to the J. Paul Getty Museum. Burton Fredricksen, the antiquities curator at the time, sent photos of the mosaic to Getty, who had taken up permanent residence in England and though working remotely, remained actively involved in his museum’s acquisitions. Fredricksen endorsed the mosaic for its high quality and excellent state of preservation. He also connected it to the Orpheus mosaic, as it was erroneously believed that the two mosaics came from the same excavation site. Fredricksen noted that the mosaic once belonged to Hearst and had a companion piece in Berg’s collection. Getty approved the Dares and Entellus mosaic for purchase.

Reunited at Last

Gallery installation of (background) Combat Between Dares and Entellus, A.D. 175-200, Villelaure, France, stone and glass. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 71.AH.106; (foreground) Diana and Callisto Surrounded by a Hunt, A.D. 175-200, Villelaure, France, stone and glass. Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Phil Berg Collection (M.71.73.9).

For the past 30-plus years, these two mosaics from Villelaure have quietly resided in their respective Los Angeles museums. Now for the first time in over a hundred years, they are reunited for public display. To top it off, they are joined by the Orpheus mosaic, offering a glimpse into the now-dispersed Hearst collection and a space to compare and experience three superb Gallo-Roman mosaics from Southern France.

A Postscript on Villelaure

View of the Tuilière field, Villelaure, 1988. Photo: Jean-Claude Rey

As the Villelaure mosaics made their journey halfway around the globe, the excavated villa was reburied. The site remained undisturbed until 2006, when a development proposal led to a survey excavation that uncovered traces of the large agricultural villa, including a long pool, foundations for walls and aqueducts, and, most excitingly, a fifth mosaic.

The central panel of the fifth mosaic found at Villelaure. Photo: Robert Gaday

The fragmentary mosaic depicts a caped figure with long boots (his torso and head are lost) surrounded by a circle guilloche set inside a square. Like the other mosaics excavated in 1900, this central panel is surrounded by a white floor with black borders along the walls. This mosaic has been reburied until further excavations can be undertaken.

The survey was not able to confirm the original location of the previously excavated mosaics, but perhaps future excavations will. To that end, a local organization, The Association of Villa Lauris en Luberon, has been working to preserve and promote the history of the site. (More information about the Villelaure excavations can also be found in the online catalogue of Roman mosaics in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum.)

Fun to hear the whole story, Nicole! Thanks for telling it.

Interesting article!