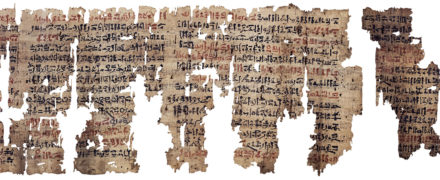

Memorial for the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall in a shopping mall (the Potsdamer Platz Arkaden). Photo: Christof Zwiener

November 9 is a peculiarly fateful date in Germany history. In 1918 this date marked the end of monarchy and declaration of the first German republic. In 1923, a young Adolf Hitler attempted to overthrow the republic with his failed “Beer Hall Putsch” in Munich. Fifteen years later, again on November 9, Hitler had achieved his ambition and, with the eager assistance of thousands of Germans, declared a night of attacks on Jewish property in what has become known as Kristallnacht, but is more accurately called the November Pogrom. And twenty-five years ago, again on November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall opened for the free flow of people between the two halves of the city for the first time since the barrier popped up overnight in 1961.

As the world celebrates the breach of the monumental barrier that divided nations and caused considerable misery, we wonder what forms of commemoration can effectively recall the process of German unification and focus attention on lessons learned from the experience of a divided Europe. As an artist whose work engages fading traces of East German culture (Christof) and a museum educator who encourages audiences to think with objects (Peter), we are both concerned with how artworks can evoke and create memories, thoughts, and reflection, as well as how the process of memory can benefit the present.

Rigged memories? Artificial section of the Berlin Wall at the Babelsberg Studios outside Berlin, in the former GDR. Photo: Christof Zwiener

The Story Behind November 9

Though the opening of the wall on November 9 resulted from a series of misunderstandings and improvisations on that day, the process making German division unsustainable had begun long before, playing out in many places far away from the Wall. In Leipzig, opposition groups held weekly meetings for many months under the watchful eyes of the notorious State Security officers. They eventually ventured considerable risk by taking their demands for reform onto the streets. Their slogan began as “We Are The People” and was only later co-opted into “We Are One People” and a call for German unification. In the years and months before the opening of the Wall, thousands of East Germans reached the point at which they were willing to abandon their homes and risk their lives to seek better conditions. Hundreds of people devised schemes to go under, over, or around the barrier. In 1989 masses of East Germans made their way to Prague and to Hungary, where the Iron Curtain was drawing back.

These movements had as much to do with discussions of opening the Wall as anything taking place in Berlin, and ultimately made the demise of the Wall inevitable.

The Wall’s Aftermath

The aftermath of the Berlin Wall’s removal forms another, still unfinished, chapter in its history. Social and economic divisions between parts of Germany formerly in East and West remain considerable. Germans are still confronting ongoing challenges: high unemployment in eastern provinces, imposition of less-generous benefits on workers, erasure of appreciated aspects of life in East Germany, and other unresolved political and cultural tensions. For many Germans, the real story of the Wall’s absence is their daily lives, including the ongoing engagement with the massive archival legacy of the Ministry for State Security, or Stasi, which compiled files on millions of citizens.

Berlin today Berlin aujourd’hui Берлин сегодня Berlin heute – III by Christof Zwiener, 2014. GDR flagpole, steel, concrete foundation (wall segment). Christof’s three-part work Berlin Today draws attention to the once-ubiquitous East German flagpoles now disappearing from Berlin’s cityscape. The first installation displayed whole flagpoles found in Berlin. A second cut a pole into 131 pieces, symbolizing transformation and destruction of East German society. In the third (shown here), Christof adopted a typical East German “make-do” attitude and utilized the pole pieces as available steel for a sculptural work, displayed near a Berlin Wall fragment as public art in Dusseldorf. Photo: Alexandra Hoener

How can an anniversary observation celebrate a triumph of democracy while also recalling this tumultuous history? How can the ceremony remind people in Germany and around the world that as we look to Berlin we must remember that democracy often means having the courage to criticize the powerful and risk one’s own well-being for the sake of progress?

In Berlin a ten-mile line of light-filled balloons has been erected along the former path of the Wall through central Berlin. On the 9th, the balloons will be released to recall the triumphant disappearance of the Wall. But will this spectacle (or the domino-like toppling of wall segments enacted at the celebration five years ago) spark serious reflection on the courage of those who opposed the Wall and the challenges of the “New World Order” that has emerged since?

“No Thinking Here”

So what exactly should we do on November 9 to promote reflection on historical change and lessons learned? The official enactments in Berlin focus attention on the path of the Wall, which was, after all, a small portion of the barrier between East and West Germany. Other significant traces of life in East Germany can still be found throughout Berlin and the eastern states but do not receive the same attention. Works of public art, for instance, have been removed or covered without consideration of how they might serve ongoing reflection. The former border crossing at Bornholmerstrasse, where guards bucked hierarchy and decided on their own to raise the barrier rather than risk injury to individuals in the crowd gathered there, could be a focus for lessons about moral action. Currently the area is marked with an uninspiring plaque and an art installation originally planned for a different location.

Fragments of the Wall (many of them genuine), which have now spread to museums and personal collections around the world, also provide an appealing physical form for memory. However, like an object in a museum, chunks of the Berlin Wall are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg, reminding viewers of a much broader and more complex story.

While material objects can usefully (and, in this case, literally) concretize moments in history, the work of artists and museum educators is to connect viewers to objects in ways that inspire active thought and a desire to make the world a better place. There is no simple or single way to do this, but we believe that celebrations and congratulatory moments must give way to more creative engagement.

“Ich bin ein Berliner.” John F. Kennedy’s words echo hauntingly in this graffito on the Israel-Palestine wall. Photo: Alexandra Novosseloff

This week we heard news that artist-activists removed 14 white crosses marking the deaths of Germans who tried to escape the Wall and placed them on new walls on the periphery of Europe, built to prevent immigrants with similar motivations from entering. In the empty spaces left by the absent crosses, they wrote, “There’s no thinking going on here.” And in Israel a photographer captured the grafitto “Ich bin ein Berliner” on the West Bank Wall. There are, in short, many contexts in which the lessons of 1989 still need application.

_______

Meet Peter and Christof on Saturday, November 15, at the free symposium New Walled Order, which considers the human urge to build—and destroy—walls.

Comments on this post are now closed.