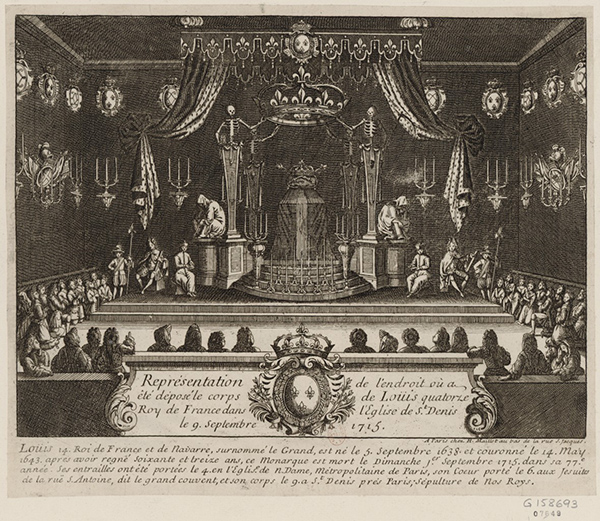

Representation of the Place Where the Body of Louis XIV, King of France, Was Laid Out in the Church of Saint-Denis, 1715, H. Maillot, publisher. Engraving, 27.2 × 32.5 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie, Qb-1 (1715). Photo credit: BnF

After suffering from gangrene, Louis XIV died a few days before his 77th birthday on the morning of September 1, 1715. His reign was the longest in French history, clocking in at 72 years. The king’s body lay in state in Versailles before it was transported to the traditional resting place of French kings, Saint-Denis, and laid to rest on September 9.

According to the inscription in the print above, one of the very few pictures commemorating the king’s death, his entrails were taken to Notre-Dame on the 4th, and two days later his heart was transported to the church of Saint-Louis des Jesuites (now the church of Saint-Paul and Saint-Louis), where his father’s heart had been deposited seven decades earlier.

It’s strange to think that the death of one of the greatest supporters of the arts, including the art of printmaking, was marked by a print of relatively modest size and quality. As one of my collaborators wrote in his catalogue entry, “Images related to [Louis XIV’s] death are rare, as if people had sought to forget this event and move on.” Costly wars, precarious state finances, religious intolerance, and a type of religious devotion that was sometimes more puritanical than spiritual cast a shadow over the final years of his reign. People wanted to move on.

This print published shortly after his death shows the covered casket of Louis XIV laid out in the abbey of Saint-Denis, where the walls were covered with dark shrouds. The king’s corpse was raised upon a pedestal, surrounded by four pillars surmounted by skeletons. One served as a symbol of Time, holding an hourglass, and another a symbol of Death, holding a scythe. Together, the four macabre figures held an enormous crown bearing the royal fleurs-de-lis. Atop the casket sat the king’s personal crown, along with a scepter and the so-called hand of justice, both of which had belonged to Louis’s grandfather Henry IV.

At the time of a ruler’s death, such symbols of earthly power were reminders of that power. But those symbols could also be employed to underscore the very futility of power. In the face of death, power is meaningless. This idea is driven home in Michel Mosin’s engraving Death Is the Wages of Sin. Here we are confronted by a large skeleton that rests upon now-useless symbols of authority while the amazed skulls of popes, cardinals, kings, and princes confront us and each other about their inevitable fate.

Vanitas with Skeleton: Death is the Wages of Sin, ca. 1680, Michel Mosin after Jean-Baptiste Corneille. Engraving, 51 × 72.3 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie, Réserve AA-5 (Mosin, Michel). Photo credit: BnF

These prints and many more are on view in the exhibition A Kingdom of Images, closing September 6, organized by the Getty Research Institute in special collaboration with the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Comments on this post are now closed.