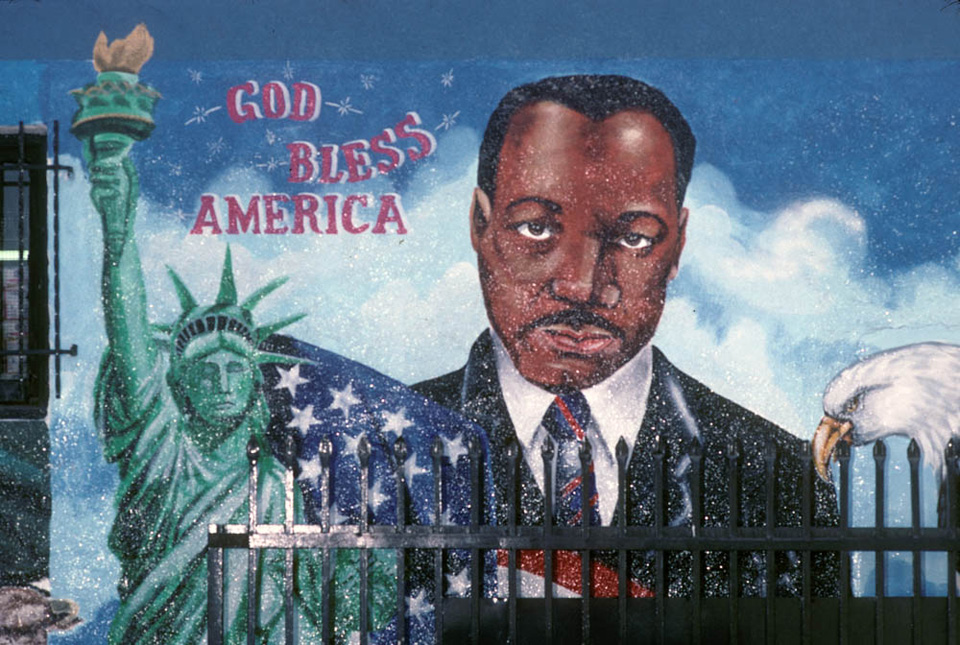

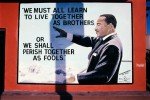

I did not set out to document murals of Martin Luther King Jr. in American cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Detroit. I just happened to find one back in the 1970s and photograph it, then many others, until a national collection developed. His likeness welcomes shoppers on the facades of liquor stores, barbershops, and fast-food restaurants. He is represented as statesmanlike and heroic, proud and thoughtful, friendly and compassionate.

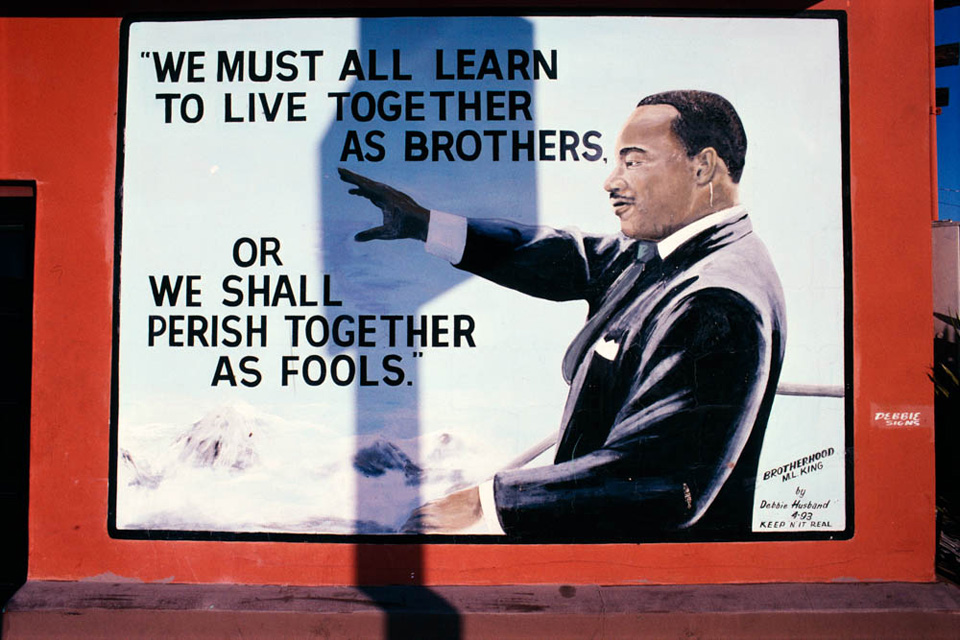

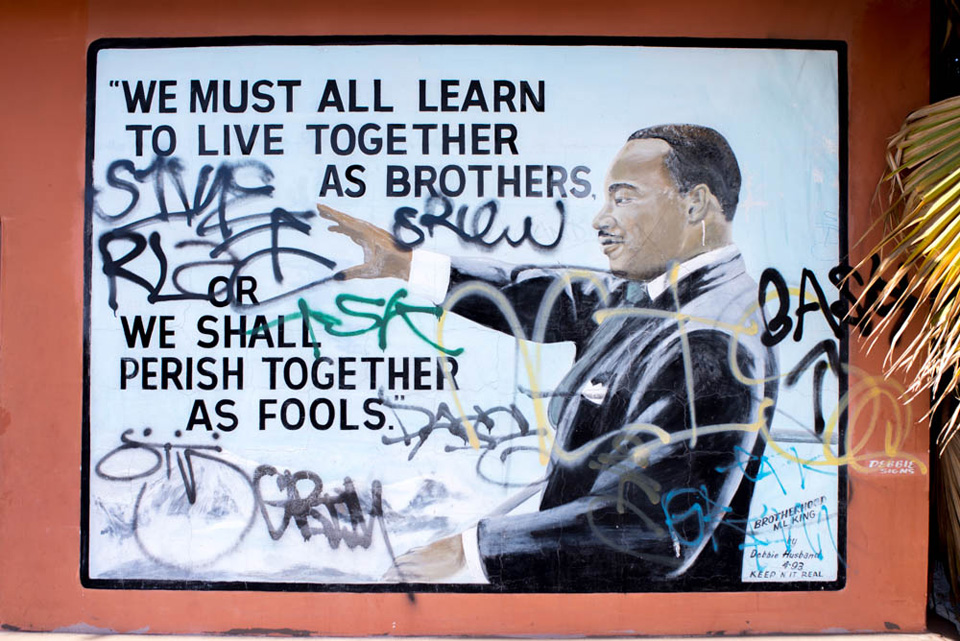

The street portraits of King are made mostly by sign painters, almost never by trained artists. Street portraits of Dr. King don’t last forever. Murals get defaced, paint fades, businesses change hands, and neighborhood demographics shift. King is typically depicted accompanied by great figures such as Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, Harriet Tubman, and Rosa Parks (though in recent years I’ve been seeing less of Mandela and Malcolm X).

The slain civil rights leader doesn’t just appear in historically African-American neighborhoods, but appears—reinterpreted—in others as well. I found a version of King in a mural remembering Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American autoworker who was the victim of a racially-motivated murder, in the ruins of Detroit’s former Chinatown. In Los Angeles, King is often depicted in the same style as other brown-skinned Mexicans in street murals by the self-taught sign painters. A friend upon seeing a photo of a mural of King remarked that he looked “Tolteca.”

Images of King mushroomed on the walls of South Central Los Angeles after the 1992 race riots. In South L.A. in 2016, King is accompanied by Pancho Villa, Benito Juárez, Cesar Chavez, and the Virgin of Guadalupe; most popular since 2009 are portraits of him alongside President Obama. Following population changes, King murals have moved west, across the 110 and toward South Western Avenue. I’ve seen street images of King disappear as his likeness is substituted by the suffering Christ or by President Obama.

As we celebrate a national holiday honoring King, we can enjoy the dialogue he inspires showing how ordinary Angelenos—and other Americans—incorporate him into their culture.

Text of this post © Zócalo Public Square. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.