Be careful during your visit to the exhibition Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment. Cupid will catch you by surprise. Using the sword of his father, the god of war Mars, Cupid is cutting a bow for himself from the club of Hercules, the divine hero whom the god of love defeated by stealing his weapon. Cupid’s mischievous smile shows his satisfaction with the flexibility of this large bow, which he is testing, and his delight with all the harm he is about to inflict. Indeed, as soon as he is finished carving, Cupid will use the bow to shoot the arrows kept in the quiver at his feet. No heart will be able to resist!

French sculptor and draftsman Edme Bouchardon carved this exceptional statue out of a single block of marble between 1747 and 1750, and it is currently on loan to the Getty Museum from the Musée du Louvre. Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club has a history befitting its passionate subject matter. It once decorated the orangery of the Château de Choisy, an intimate refuge for one of the most famous couples of eighteenth-century France: King Louis XV and his mistress Madame de Pompadour.

Cupid, 1750, Edme Bouchardon. Marble, 68 1/8 in. high. Musée du Louvre, Département des Sculptures, Paris. Image © Musée du Louvre / Hervé Lewandowski

Bouchardon’s carving skills are evident Cupid’s accessories, each of which corresponds to a mythological god or hero. The advantageously feathered helmet, the sheath, with the artist’s signature on the baldric, the sword—the hilt of which is decorated with a French fleur-de-lis, as the statue was a royal commission—and the shield with its cord are the weapons of Cupid’s father, Mars. The club, nearly carved out entirely, and the Nemean lion skin resting on the tree trunk, which serves as a support for the statue, are the attributes of Hercules. Of course, the bow and the quiver, decorated with foliated scrolls and filled with arrows, are the weapons Cupid will wield to make his victims fall in love.

Many details, such as Cupid’s wings with their thick, soft feathers that taper downward, are truly virtuosic. The incredible variation among the surfaces provides a contrast with the smooth skin of the young god, enhancing his elegant body. By giving the figure an amazing twirling posture, which entices the viewer to keep moving around it, Bouchardon created a statue whose captivating nature wonderfully echoes the powers of Cupid.

Installation view at the Getty Center of Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club (detail) by Edme Bouchardon, courtesy Musée du Louvre, Paris

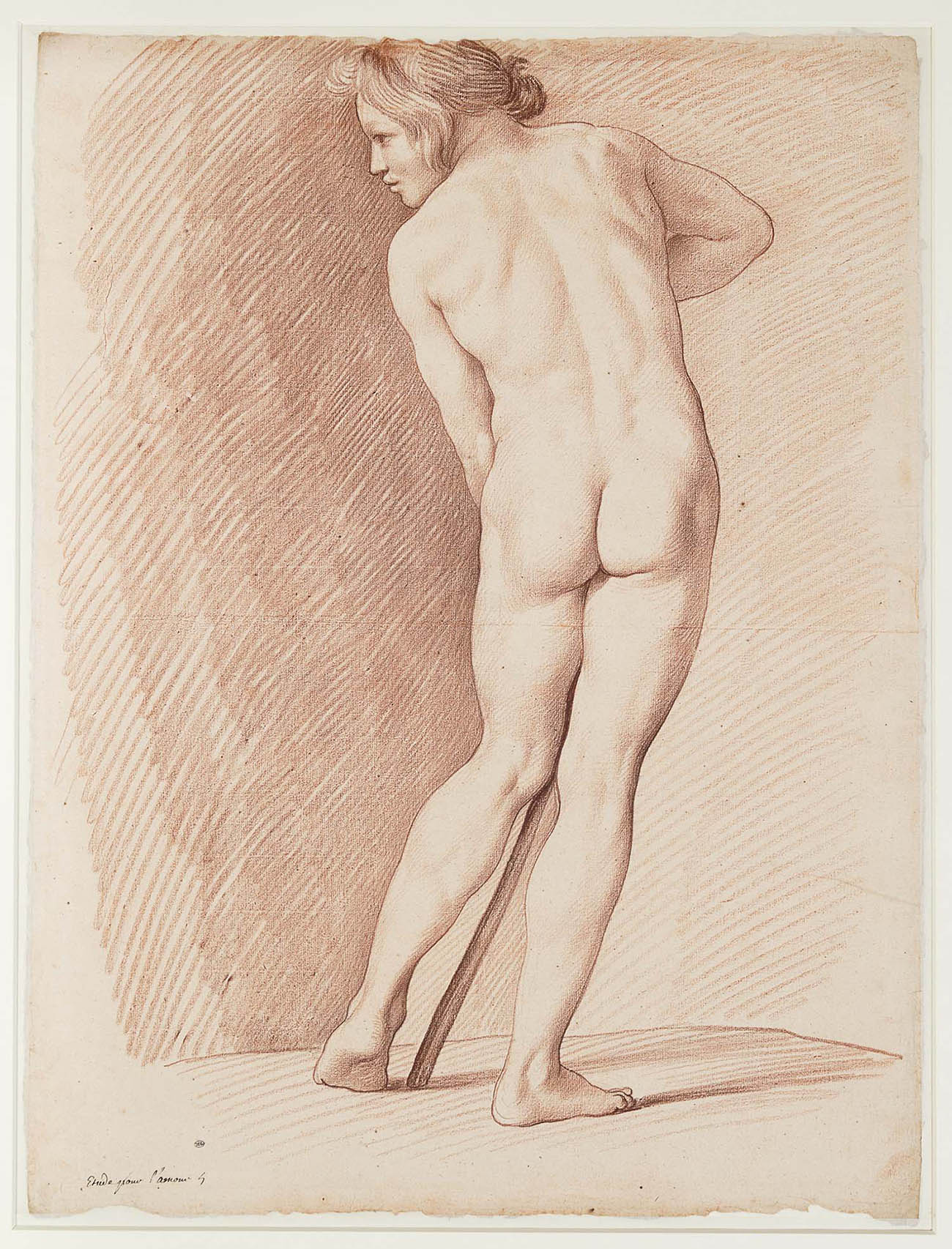

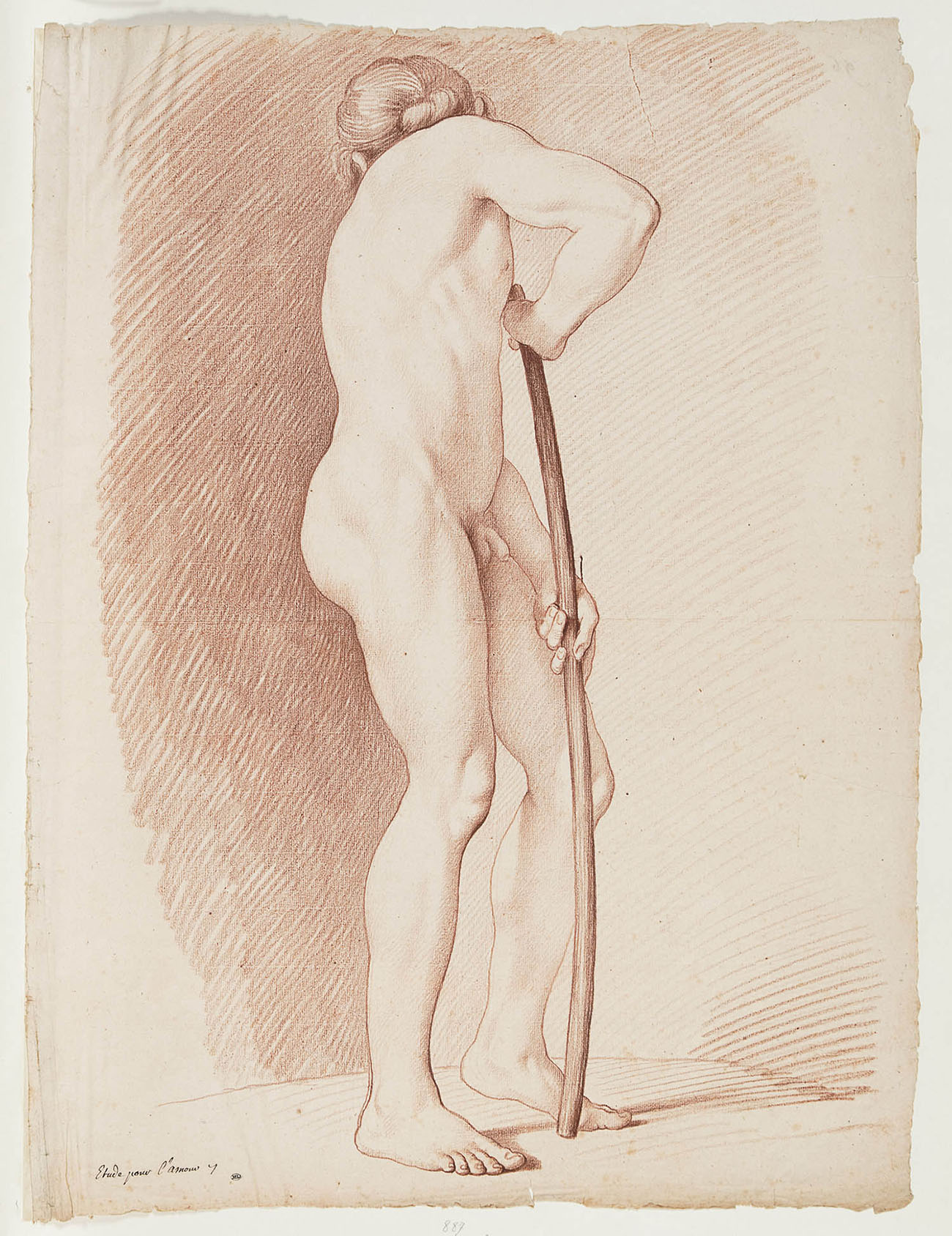

In planning the statue’s composition, Bouchardon undertook scrupulous preparatory work, studying antique works of art as well as the body in nature, making drawings from a live model. To ensure the sculpture could be appreciated from multiple viewpoints, the artist examined and drew the model from different perspectives to capture the figure’s three-dimensionality.

Nine of these red-chalk drawings are conserved at the Louvre, and three are on view in the Museum’s exhibition. They show how Bouchardon focused on the contours of the body and how, by sketching with lighter and smaller lines, he meticulously rendered the softness of the flesh, the muscles and bones under the skin, and the effects of light and shadow.

Model Posing for Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club: Young Male Nude Seen from Back, Left Profile, about 1745, Edme Bouchardon. Red chalk, 23 7/8 × 18 3/16 in. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques. Image © 2015 Musée du Louvre / Laurent Chastel

Model Posing for Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club: Young Male Nude, Body Turned toward the Right, Head Seen from Back, about 1745, Edme Bouchardon. Red chalk, 24 3/16 × 18 5/16 in. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques. Image © 2015 Musée du Louvre / Laurent Chastel

While Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club is one of Bouchardon’s most celebrated masterpieces–”that will be forever admired” foresaw the philosopher Diderot–eighteenth-century sources report that “This figure was not well received at the Court.” Put on display in the center of the Hercules Salon at Versailles, “it drew criticism from all the little mistresses and all the courtesans.” Moreover, as the engraver and art critic Charles Nicolas Cochin (French, 1715–1790) wrote in his biography of Bouchardon:

“On that occasion, the Court gave good proof of its ignorance, of its lack of taste for the arts. What, so that is Cupid, they said, but it is a Cupid porter; but, that is not at all pleasant. . . . As it is the opinion of pretty women that decides everything in this country [France], and they did not find it to be the type of musky plaything they like, it was so discussed and criticized that it had to be removed from there, despite the artists, who called it a marvel, but who were regarded as imbeciles.”

While many rejected the statue because they perceived it as overly realistic for the subject matter, there was also a deeper, more political negative reaction. Once finished in 1750, the statue was first installed at Versailles in the War Salon, the room at the north end the Hall of Mirrors. The presence of the mocking Cupid—using the weapons of the god of war to carve a bow—must have seemed offensive in this room, where the Sun King Louis XIV is represented in a marble relief as a royal conqueror leading his armies.

The statue was then moved to the Hercules Salon, whose ceiling depicts the apotheosis of this hero, an allegorical representation of the King Louis XV. Placing a statue illustrating the defeat of Hercules, whose club has been turned into a bow by the god of love, beneath such a ceiling was quite daring. Furthermore, the Hercules Salon was located on the way to the royal chapel. The presence of an artwork celebrating the triumph of Cupid was particularly shocking in this location, as Louis XV was openly having an adulterous affair with Madame de Pompadour. Perhaps aware of the criticism of the statue, the king did not want the sculpture to remain at Versailles. By 1754, it had been sent to the Château de Choisy to be displayed in the orangery. Used as a retreat by Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour, this was the most appropriate site one could choose for Cupid!

Installation view at the Getty Center of Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club (detail) by Edme Bouchardon, courtesy Musée du Louvre, Paris

Valentine’s Day may be today, but you have until April 2, 2017, to visit the Getty Museum and see Cupid Carving a Bow from Hercules’s Club, one of the most beautiful and charming depictions of the god of love, whose large bow, numerous arrows, and mischievous smile will make you fear for your heart.

Madame the Curator,

Your article is weighted and exciting.

Do you not give too much importance to love in this history of relegation of the sculpture ?

Louis XV, as his ancestors since Henry IV, is often compared to Hercules.

Perhaps he did not much appreciate being tamed, who knows ?

Excuse my junk English learned in Saudi Arabia fifty years ago…

Even if you are French.

Cl Bx

130, rue Seyssaud

84200. Carpentras.

France