Three years ago this week the Getty announced the launch of our Open Content Program, making available 4,600 high-resolution images from the Getty Museum and Getty Research Institute collections for anyone to use, modify, and publish anywhere for any purpose. In his announcement, our president Jim Cuno hinted that more content would be made freely available for reuse in the months to follow, including digital publications and other knowledge resources.

And more content did follow: since 2013 the Getty has released over 100,000 more images through the Open Content Program, and we are increasingly using open licenses for Getty-developed content including selected digital publications, Research Institute archival finding aids, Getty Museum online collection data, Getty Conservation Institute teaching and learning resources, and even the very blog you are reading right now. Throughout, our priority in developing openly licensed resources has been to make the Getty’s work as widely available and usable as possible, while retaining the right to attribution.

Digital access to cultural resources helps foster understanding of the arts, and is key to our mission and our responsibility to the professional communities we serve. But open access and open licensing represents a fundamental shift in how the Getty conceptualizes, creates, and disseminates its own intellectual property. And as we’ve been finding, implementation is often easier said than done, particularly for projects that were conceived before but published after the Getty’s full embrace of open content.

On this third anniversary of the Open Content Program’s launch, we share some of the lessons learned along the way, focusing on two recent projects from the Research Institute that required significant collaboration between the Getty’s legal team (Mikka) and the Research Institute’s digital art history group (Nathaniel and Marissa).

Creative Commons: Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681

Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681, or Mellini for short, is an online publication including a facsimile of Mellini’s rhyming inventory of his family’s art collection from 17th-century Rome, scholarly essays putting the document in context, and a partially illustrated list of artworks from the inventory. Mellini is now available under a Creative Commons-Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY).

We decided to make Mellini CC-BY only after it was published. After seeing a presentation on the project by principal investigator Murtha Baca, Mikka inquired about the rights status of the project and whether it could be published under some form of open license. It seemed like an ideal candidate for a number of reasons:

- The object itself (Mellini’s inventory) is in the Research Institute’s collection, so no lender permissions were required,

- The object is in the public domain by virtue of its age, so no copyright restrictions applied to the object itself or its facsimiles, and

- The translation and related essays are all by Getty staff or were commissioned by the Getty as works made for hire, so the Getty owns the copyright for all the texts, and

- The artworks reproduced are also in the public domain and, in many cases, unrestricted reference images could be found on Wikimedia Commons.

(Note: The Wikimedia Foundation, like the Getty, takes the position that faithful reproductions of two-dimensional public domain works of art are themselves in the public domain, because they lack the originality required for copyright protection. See Bridgeman Art Library v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191, 196–97 (S.D.N.Y. 1999); see also Feist Publ’ns v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., Inc., 499 U.S. 340, 359–60 (1991)—“originality, not ‘sweat of the brow,’ is the touchstone of copyright protection . . . .”)

Pietro Mellini’s Inventory in Verse, 1681 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY), except as noted.

Working together, we ascertained that a CC-BY license could legally be applied to the vast majority of Mellini. The only sticking points were the handful of images from third-party sources, for which permission had been sought and granted before the decision was made to make Mellini open access. In other words, the original permissions requests were simply for a digital publication, without any mention of CC-BY licensing, and thus contractual considerations prevented us from openly licensing the material.

The legal and technical challenge, therefore, was figuring out how to apply the CC-BY license to the Getty-owned and unrestricted content, while excluding the third-party materials in which the third parties reserved all rights. This involved both crafting a sufficiently clear written message in the project’s copyright notice for the benefit of human readers, and adding machine readable text (HTML-level tagging) to communicate the rights status of individual elements to web crawlers as well.

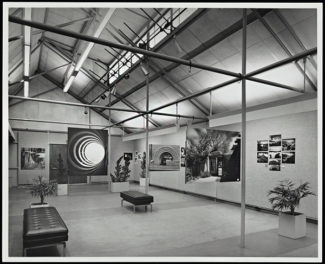

GNU: Getty Scholars’ Workspace

Getty Scholars’ Workspace is a digital collaborative research environment for art historians. From its inception, it was conceived as an open-source digital tool that would be released for free to the scholarly community (or anyone else that might want to use it!). It was developed in Drupal, an open-source content management system (CMS) used principally for developing websites. Drupal enjoys an active community of programmers who contribute modules to the CMS.

Even though the intent was always to make the source code for Getty Scholars’ Workspace openly available, the bulk of it was developed before the Getty’s full embrace of open access, and before the Getty had internalized best practices for in-house development and licensing of open-source software. Thus, as with Mellini (which coincidentally used an early version of Getty Scholars’ Workspace during its research phase), the decision to pursue open licensing was easy—but the implementation (especially determining which open-source license to use) was not.

Getty Scholars’ Workspace was developed in version 7 of Drupal and uses a combination of modified and “out of the box” modules from the Drupal community. All Drupal community modules are published under the terms of GNU General Public License, Version 2 or later. However, Getty Scholars’ Workspace also employs a number of open-source modules that are not part of the Drupal community and, as such, were released under whichever license(s) their authors deemed appropriate.

Furthermore, many of the twenty-eight modules custom-built by the Research Institute contain lines of code borrowed from third parties, a common practice in the open-source community. This means that multiple external licenses govern even the modules that were built by or for the Research Institute, on top of the GNU GPL governing the Drupal components. And we needed one license to rule them all.

Choosing the right license was a matter of identifying the open-source licenses that best complemented the Getty’s priority (to make the work as widely available and useable as possible while retaining the right to attribution), and then determining which licenses would be compatible with the many dependent license agreements embedded in various parts of the software. To accomplish this, we needed the help of an outside consultant to comb through license terms for more than 5,000 files in 121 directories comprising the codebase. And all this had to be done in a very short timeframe in order to meet the completion deadline required by the project funder. Finally, after extensive analysis, Getty Scholars’ Workspace was released to the public under the GNU General Public License, version 3.

Getty Scholars’ Workspace on GitHub. The code is licensed under the GNU General Public License, version 3.

Takeaways

The challenges of working with open-access and open-source materials are endemic to any novel framework or paradigm: because it is so new, most of us are learning as we go. Working on Mellini and Getty Scholars’ Workspace has left us with a few takeaways.

First, it’s important for the institution to clearly understand—and be able to articulate—why it values open licensing, and to be able to distinguish between the projects that can and should be openly licensed and those that can’t or shouldn’t be.

Second, it’s much easier to build an openly licensed project from the ground up than it is to make a project open after the fact. When open access is a project goal from the outset, it helps guide decision-making, especially with respect to contracts with collaborators and consultants, and the sourcing of images and code. Third, open-source software licensing is not for the faint of heart, especially when the software is built from many pieces of preexisting code (which is helpful during development but can complicate release).

The good news is that having one piece of restricted content doesn’t have to prevent the rest of the project from being licensed openly. Creative Commons licenses by their terms are applied to “Licensed Material,” and that “material” can be defined to include as many or as few elements of a project as are appropriate. However, because the world of open licenses, and especially its embrace by the galleries, libraries, archives, and museums sector, is relatively new, we don’t have clear precedents or on-point examples to follow for this kind of selective licensing, particularly when it comes to making the human-readable text understandable and ensuring the accuracy of the machine-readable text. For Mellini and Getty Scholars’ Workspace, we’ve done the best we can in support of the Getty’s open-access goal; we look forward to seeing and learning from what others do, and to continuing to contribute to the growing pool of freely available cultural resources.

Comments on this post are now closed.