Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) was a prolific printmaker whose work explored painful themes such as hunger, poverty, and death. To achieve her powerful results, she employed a wide range of printing techniques and created numerous drawings and working proofs as part of her process. A new exhibition at the Getty Research Institute, Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics, showcases her working methods through pieces donated as a partial gift in 2016 by Dr. Richard. A. Simms.

Simms, born in New Orleans 1926 and a dentist and orthodontist by trade, is a dedicated collector of prints and drawings who came to Kollwitz’s work by chance. The Dr. Richard A. Simms Collection at the GRI contains more than 650 nineteenth- and twentieth-century works by Kollwitz.

In this episode, Dr. Simms discusses his unusual path to becoming a collector and the appeal of Kollwitz’s art. Getty Research Institute exhibitions coordinator Christa Aube, who co-curated the exhibition with Louis Marchesano and Naoko Takahatake, joins the conversation to lend insight into Kollwitz’s working methods.

More to explore:

Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics exhibition

Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics publication

Richard A. Simms Collection

Transcript

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

CHRISTA AUBE: Kollwitz was interested in those who are left behind—the widows, the mothers, the children.

CUNO: In this episode I speak with the distinguished art collector, Dr. Richard Simms, and Getty Research Institute exhibitions coordinator Christa Aube, about the exhibition Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics.

Dr. Richard Simms was born in New Orleans in 1926, graduated from Xavier University, served in the US Army during the Second World War, took his dental degree from Howard University, and then settled and in Los Angeles, where he’s worked for more than sixty years.

Over that same period of time, Dr. Simms has built a renowned collection of modern master prints, especially those of expressive realist artist, Käthe Kollwitz. Kollwitz was born in 1867 and died in 1945. She came from a politically active, socialist family and began drawing lessons when she was twelve years old. She is best known for her prints and drawings, which often focus on difficult subjects such as hunger and death. Her work is the subject of an important and moving exhibition at the Getty Research Institute, Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics, drawn from the more than 650 prints and drawings Dr. Simms gave to the Getty in 2016.

I recently toured the exhibition with Dr. Simms and the Getty Research Institute’s exhibitions coordinator Christa Aube. We recorded this podcast in the exhibition galleries.

CUNO: Thank you Richard and Christa for joining me on this podcast. Now Richard, you were born and took your medical degrees in New Orleans. Tell us what life was like in those early years, in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s.

RICHARD SIMMS: I was born in 1926. I went to college in New Orleans, 1942. And I was sixteen. And they couldn’t afford to send me to college, but the university gave the incoming freshmen tests in English, in French, and in math. And the three highest scores among the freshmen got their tuition for free.

And so I figured out which one I wanted to take, and I took English. And I took that test and I won one of the three scholarships that were given in English. Then I stayed there until December 1944, when I was eighteen and I was drafted.

CUNO: So that was at Xavier University of Louisiana.

SIMMS: Yes. And I stayed in college on an accelerated program, because it was during the wartime and every college, university was speeding up the degrees.

I then went first to Camp Chaffee, Arkansas. Why? It’s an induction center. And then by train, from there through St. Louis to Fort Dix, New Jersey. And I was put in a medical detachment. Each one of the medical detachments had a black officer as its physician.

We were put on a troop train from there, to go to Seattle. And thence by boat, to the Pacific. And it took us thirty days to go to— I remember the ship, SS George Flavel. It was a converted tanker of some sort, a product-carrying ship. And we left there and we stopped in Guam, and then landed in Saipan. And I was in Saipan for about two years, and I was a staff sergeant in charge of a medical detachment. And the physician, by that time, had changed from black officers to white officers.

And with the dropping of the bomb by Harry Truman, the war ended for us. And so I was discharged, sent back to Fort Sam Houston for discharge. And when I left there, I came home and I worked at a medical supply house called Aloe, A-L-O-E, a St. Louis company. And because I had experience in chemicals and things like that, I was put in charge of the laboratory part of it, the equipment.

I got out of the service in ’44 or thereabouts, ’45, went back to college and finished a year and I was done with college. I graduated in 1947. And then I went to dental school at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

And I was practicing in general practice, with a minor reference to oral surgery. I stayed in New Orleans for roughly two years, from ’50 to ’51. I did not find Louisiana the right place to practice. So I get an invitation from a man in California, his name was Max Schoen, S-C-H-O-E-N, who wanted to know if I wanted to practice with him. And after listening to what he had in mind, I decided to move to California. So I come to California.

And he was starting a practice in a working-class subdivision of Los Angeles called Wilmington. And the objective that we had after we started was to work on longshoremen. Which is similar to Kollwitz’s husband who worked for tailors in a, what is called a tailors cranking house. And then we decided to move, as we got busier, and we bought land in a place called Harbor City, which is next door to Wilmington.

And then finally, we decided we needed an orthodontist, because we were a revolving door for orthodontists. And the objective was to educate each one of us in different specialties, so that we could continue to practice what we needed. Wilmington is not a place where people in Los Angeles wanted to go. So we had to educate our own.

CUNO: Right, right. OK, Richard, now tell us about how you first became involved with art.

SIMMS: I was introduced to the arts when I was in college. The Catholic college I went to had a splendid library, detached from the administration building. And you walked in a side door, and to the left there was another door that was kept locked. And then you’d turn and go upstairs. And on isolated occasions, the locked door was open.

I walked in on one of those occasions when it was open, and I saw black American sculpture. Specifically, an artist named Richmond Barthé, B-A-R-T-H-E. And mentally, it registered, as to what it was. And then I went on upstairs and did what I was in the library to do, and then I left.

There was something else that introduced me to it. There use to be an ad in national publications called “Draw Me.” And it was for an art school in either Wisconsin or Minnesota. And if you could draw this picture and send it to them, they would let you know whether you had the talent to be an artist. I participated in this “Draw Me” thing. I must’ve been thirteen through sixteen.

And my grandmother had an enormous influence on me. I had to read to her every day and she read to me. And she was not an educated woman. She was a domestic. In other words, she worked for Caucasians some other place. And she walked with a rock. And she was one of six children, and they were born all in Nacogdoches, Louisiana. North of New Orleans, but south of Shreveport, the border of Arkansas and Louisiana. And I never knew her family.

But I had to read to her every day, and she read to me. And she talked to me a lot about what I should do or wanted to do. And I told her that I wanted to be an artist. And she spoke to her daughter—not yelled to her—my mother. And she said, “Minnie—” her name was Louise, but my grandmother called her Minnie. And she said, “Minnie, did you hear what this boy just said? This boy said he wants to be an artist.” And she then turned to me and she said, “Boy, you are going to become a doctor.” And that was the end of that conversation.

CUNO: [laughs] Ok. Now I recall, though, very clearly, that you and I first met here in Los Angeles in the 1980s. I was head of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts and you were already a notable collector of prints and drawings by Käthe Kollwitz. This is not to say you didn’t collect works by other artists, but you had a very demonstrated interest in works by Kollwitz.

When did you first begin collecting prints and drawings?

SIMMS: I had always been interested in art. And I went to museums here. And there was a dealer on La Cienega Boulevard, whose name was Oriel P. Reed[sp?]. O.P., the initials he went by, Reed. And he did German printmakers. Another person involved in it was Zeitlan and Ver Brugge. And across the street from that was Heritage Gallery, who dealt in a variety of artists, including black artists. And so the man who owned it was Benjamin Horowitz. And I bought my first works from him.

CUNO: When, what year was that?

SIMMS: Probably ’61.

Now, my early years of practice, I was collecting black American artists. And my wife and I went to Boston, for me to attend a course in growth and development. And it was my first opportunity to go into the MFA.

CUNO: That’s the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

SIMMS: In Boston, that is correct. And there, I saw Winslow Homer’s treatment of black people and Thomas Eakins’ treatment of black people. And I decided, after seeing those two men and the work they did, I could not afford to collect black artists only.

And so I went to O.P. Reed’s gallery, and he showed me a Dürer. And it was a heraldic Dürer, a coat of arms with cock, a rooster, sitting on top of it. And I had no idea what it was and I had no books, so I went to the public library downtown. I went after office hours. And by the time I studied whatever books there were in the main library, public library in Los Angeles, I then realized that that was not a bad work; I should buy it. And when I went back, it was gone.

CUNO: Oh no! Well that’s the plight of the collector I guess—always remembering the one that got away. So then what was the first Käthe Kollwitz work you bought?

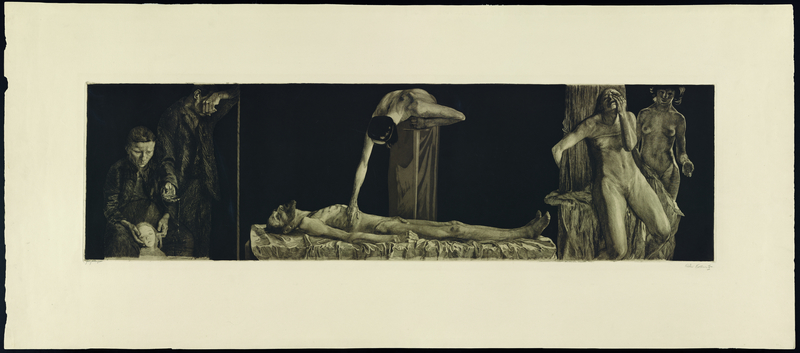

SIMMS: If you look in my collection, there is a long something called a triptych. And it’s called Zertretene, The Downtrodden, which is the title of it.

The Downtrodden was a mixed subject. On the left side of it as you view it, was a man standing; and he was handing his wife a lariat or a rope for which to hang the child with. The inference was that this child was going to die or had already died.

CUNO: I should emphasize to our podcast listeners that we’re looking at the catalogue of the exhibition, at a print reproduced in the catalogue. It’s a triptych, that is a print on three sheets of paper, titled The Downtrodden, dated 1900. It’s an exquisite etching, drypoint and aquatint of dead and dying, suffering people.

Now which sheet of the three did you buy?

SIMMS: I bought the left-hand side, one-third of it. That plate had been separated. And you could buy the left half of that, being different from the right half. There’s a very great difference between the subject matter of this. That’s the first time I’d seen her work.

CUNO: Now why did you buy the left hand side, not the middle and right ones?

SIMMS: It wasn’t for sale. It had been severed. You know, it had been cut apart.

CUNO: Well what was it about this print that attracted you?

SIMMS: The subject matter. It was unlike the other two-thirds of the plate. You can see that for yourself. This is a very realistic part of the plate on this side; and the other two-thirds of it are not as realistic as that.

CUNO: Did you know then that you would collect much more of Kollwitz’s work?

SIMMS: Oh, I can’t say I knew that that’s where I was headed. But let me say this to you. By comparison, I’ve never been interested in Mary Cassatt, because of the difference in the subject matter.

CUNO: Right, right. Well when did you buy your second Kollwitz print?

SIMMS: I don’t even know what it was.

CUNO: I see, I see. Now Kollwitz made sculpture, too, didn’t she? Did you ever think of collecting her sculpture? Or the sculpture of her contemporaries?

SIMMS: She did sculpture. And her mentor was Ernst Barlach. And people have asked me, why didn’t I collect Kollwitz sculpture. But Ernst Barlach was, for me and for many other people, the sculptor of Germany of that period.

CUNO: Yeah, with that vigorous, expressionist sensibility. I mean, he had the subject matter, too, of hard-working people, so much like the work of Kollwitz.

SIMMS: Yeah. The same subject matter.

And a group of them were put up for sale at some gallery in central Germany. And that was the first time I’d ever seen anything offered for sale in that quantity. And then it disappeared from the market. The city that Barlach lived in wanted it all. And so they wouldn’t let it be sold.

CUNO: What about other artists. When speaking of Kollwitz, one thinks of van Gogh, for example. Did you ever get interested in his prints?

SIMMS: Well, Vincent van Gogh is— He comes at a later time for me. In my life. I was interested in Germans, going way back.

And Vincent van Gogh… I did buy one. A drawing. It is a portrait of his psychiatrist. A portrait of Dr. Gachet. I had an opportunity to buy it within the last year, or within maybe a little more than a year.

And I’ve given it to the Getty. I had bought it and it was already here, and I decided I would like to give it in memory of Deborah Marrow.

CUNO: Well, Richard, that’s so kind of you. Deborah would have been very grateful for that, so thank you.

Now, let’s go on to the second gallery. This gallery includes prints from Kollwitz’s cycle titled The Peasants War. I think they are quintessential Kollwitz prints, in subject matter and technique. Christa, tell us how you began to install the exhibition.

AUBE: Well, we had so many incredible works in this collection from which to choose. So it’s almost 300 prints and drawings by Kollwitz. And so we wanted to show a representative sampling of her prints, of her preparatory drawings, of rejected versions, of working proofs, and really show our visitors Kollwitz thinking things through on paper. We were interested in sequences of images and showing series of works that show her starting with one composition, rejecting it, and then ending up somewhere completely different.

Her Weavers’ Revolt cycle was her first cycle of prints. And that brought her considerable renown early in her career, in the 1890s. So this is the second cycle that she produced. It’s a series of seven works, and this is the first decade of the twentieth century.

CUNO: Yea. Now, Richard, how long did it take you to acquire all of the sheets in this series, The Peasants War?

SIMMS: You, in posing the question, you’re not taking into account the fact that you buy what’s available. You don’t have the opportunity to go back to the first, as opposed to something else. You buy what’s available for you at the time, whatever comes up.

CUNO: Ah, I see, that’s probably the case. But give our podcast listeners a sense of the imagery of the prints that we’re looking at.

SIMMS: It is a peasant woman looking at men who are plowing a field. They have harnesses on their backs. The figure behind has the working part of the plow, right here. And they have it across their shoulders. And this is a man with a hand trowel or plow.

CUNO: Yeah, Christa?

AUBE: There was something about the image that we’re looking at first here on the wall, the lithograph showing the woman and the two men are pulling the plow before her. She wasn’t satisfied with the image. She wanted to reduce it to a simpler composition. And so in the later version, where it’s an etching, the woman is no longer shown actively leading the men with the plow, but she’s shown standing in the foreground. And then in the later composition for The Plowmen, the woman does not appear at all.

So for the sheet that we’re looking at right now, The Plowmen, which is the first sheet in The Peasants War cycle, she actually starts in lithography, and then rejects this version and then turns to etching. I think etching and mixing these intaglio processes really allowed her to build up these layers of tone and texture to give a real mood to the works in The Peasants War. And it was the right language for her in the first decade of the twentieth century.

CUNO: Let’s move on to the second sheet in the cycle called Raped. We have a preparatory drawing for the print, and the print itself here on display. Christa, could you describe the print for us?

AUBE: It’s a challenging subject. We see this woman’s body sort of splayed out in this landscape.

The Peasants’ War, the subject comes from the sixteenth century Peasants War. And so Kollwitz is giving us sort of a modern reimagining. We’re seeing peasants and workers pushed to their very breaking point. We’ve already seen The Plowman, the oppression, the suffering. And then in Raped, we see how this woman has suffered. And it’s going to be experiences like this that are going to lead the peasants to revolt in the Peasants War.

CUNO: Now the subject matter seems to foreshadow the violence of the First World War, which will of course begin in less than a decade.

AUBE: Absolutely. I think she’s just showing the horror, the brutality, the violence, the suffering of the working class.

SIMMS: In response to the war of 1917, she lost a child. And she has pictures of mourning parents that are bronze, in a cemetery in Belgium. She did many pictures of the parents, the parents affected by the loss of that child in the war.

CUNO: Yea. Now what about two impressions of a print titled Arming in a Vault from 1902. Richard, this one on the left, the lithograph, is bold in its use of color, bright fiery oranges and reds. What can you tell us about this print?

SIMMS: This particular print, two New York dealers bought it for me at an auction in Europe. And I knew it was coming up. And so they were authorized to just whatever they wanted to do to get it. This collection was from a woman who hid it for, it was in a room and she built a wall so that nobody would know that there was a room behind that. And this was one of those.

CUNO: And where was that?

SIMMS: It was in Munich, I think it was in Munich.

CUNO: Now let’s look over here at one of the most renowned of Kollwitz’s prints, called Sharpening the Scythe. Christa, could you describe it for us?

AUBE: Well, for the third sheet in the cycle, which was Sharpening the Scythe, we actually begin with a working proof for the rejected version for this sheet. And it was called Inspiration. We have two impressions on the wall here. And Kollwitz originally had envisioned it as this sort of male allegorical presence who is inspiring this peasant woman to rise up, to take her scythe, to turn it into a weapon of war.

So we’re seeing this moment where he is leading her into her decision to rebel and revolt. Kollwitz tweaks this composition a little bit and actually shows the woman, her hand on a scythe, taking some agency. Ultimately, however, Kollwitz rejects this version of the composition and changes the format quite a bit, from a more vertical, rectangular composition to a square format, where she’s only focusing on this peasant woman who is now holding the scythe in front of her face.

SIMMS: Well, she’s sharpening it.

AUBE: Yes, exactly. She’s sharpening it. In the first print that we have here on the wall, you can see that her arm is draped over the blade of the scythe.

In the Simms Collection, there’s a preparatory drawing showing the woman with her arm on the blade of the scythe. So Kollwitz wants to make this scene a bit more active and actually, instead of having the arm draping over the blade, shows, in these later impressions, the woman is actually sharpening the blade with the whetting stone. So a much more active pose here. She is turning this scythe into what will become a weapon of war. She has decided that she is going to participate in the rebellion, in the revolt.

CUNO: Now she was herself a manifest pacifist. Isn’t that right Richard?

SIMMS: Yes. She was a pacifist.

JIM: Christa?

AUBE: She loses her youngest son in 1914, in the early months of World War I; and then her grandson in World War II. I think it’s 1942 or 1943.

CUNO: She didn’t survive the war, she died before it ended, right?

AUBE: She dies shortly before the end of World War II.

CUNO: Yeah.

AUBE: Something that Dr. Simms talks about quite frequently is that Kollwitz was interested in those who are left behind—the widows, the mothers, the children—and that Kollwitz isn’t showing moments of great action—

SIMMS: [over Aube] You never see battlefields, you never see, as she’s just said, any action. She is concentrating on the ones that left behind, whether it’s the children or the wives of alcoholics or whether it is the children that are home. To have a child die in the war is a tragedy of the utmost, for her.

CUNO: Yeah it surely is. It makes me think, seeing these scenes of vulnerable women and children, and mothers and children, sort of make me wonder if part of their attraction to you might be related to stories your grandmother told you or the circumstances in which she lived and worked in the South when you were a child. Is there anything to that?

SIMMS: Well, I don’t relate it to that at all. In other words, my mother and grandmother lived together, and my father lived in Chicago. And my understanding is that his wife, my mother, said that her mother got ill and she would go to New Orleans to take care of her. And he said he would join her soon, and he never did.

I met him once when I was in seventh or eighth grade. A woman took my brother and myself to Chicago on a train to see him. And my feeling is that he did not wanna live in the South. That was my real thought about it, that if they had stayed in Chicago, he would have stayed with her. Or they together. But they were separated; they were never divorced. And I believe that it’s due to him not wanting to live in the South.

As a child, I’m glad I lived in the South. I wouldn’t wanna live in the North. I see too much of what it does. We had a house with a porch and a swing and flowerpots, and a backyard with chickens in it. And a neighbor down the street had a bigger yard with more chickens in it.

But when I went to visit my father, he worked in a grocery store. And as I’ve gotten older, I realize that his position in that grocery store, when I think back on it, is that he was bagging groceries. And the guy that’s bagging the groceries isn’t making a lotta money. So I’m happy that I grew up in the South. I enjoyed it.

CUNO: Well, Richard, thank you, thank you so much. Richard and Christa thank you both for your time this morning on the podcast. But Richard thank you especially for giving your collection to the Getty Research Institute where it will be kept and made available to the public forever. So thank you both, very much. Richard, thanks again.

SIMMS: Thank you. I enjoyed it. And I must part with it. And so I’m kinda grateful that I found a place for it.

CUNO: Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics will be on view at the Getty Center through March 29, 2020.

Our theme music comes from “The Dharma at Big Sur,” composed by John Adams for the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2003. It is licensed with permission from Hendon Music. Look for new episodes of Art and Ideas every other Wednesday. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts or Google Play Music. For photos, transcripts, and other resources, visit getty.edu/podcasts. Thanks for listening.

JAMES CUNO: Hello, I’m Jim Cuno, president of the J. Paul Getty Trust. Welcome to Art and Ideas, a podcast in which I speak to artists, conservators, authors, and scholars about their work.

CHRISTA AUBE: Kollwitz was interested in those who are left behind—the widows, the mothers, the c...

Music Credits

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.