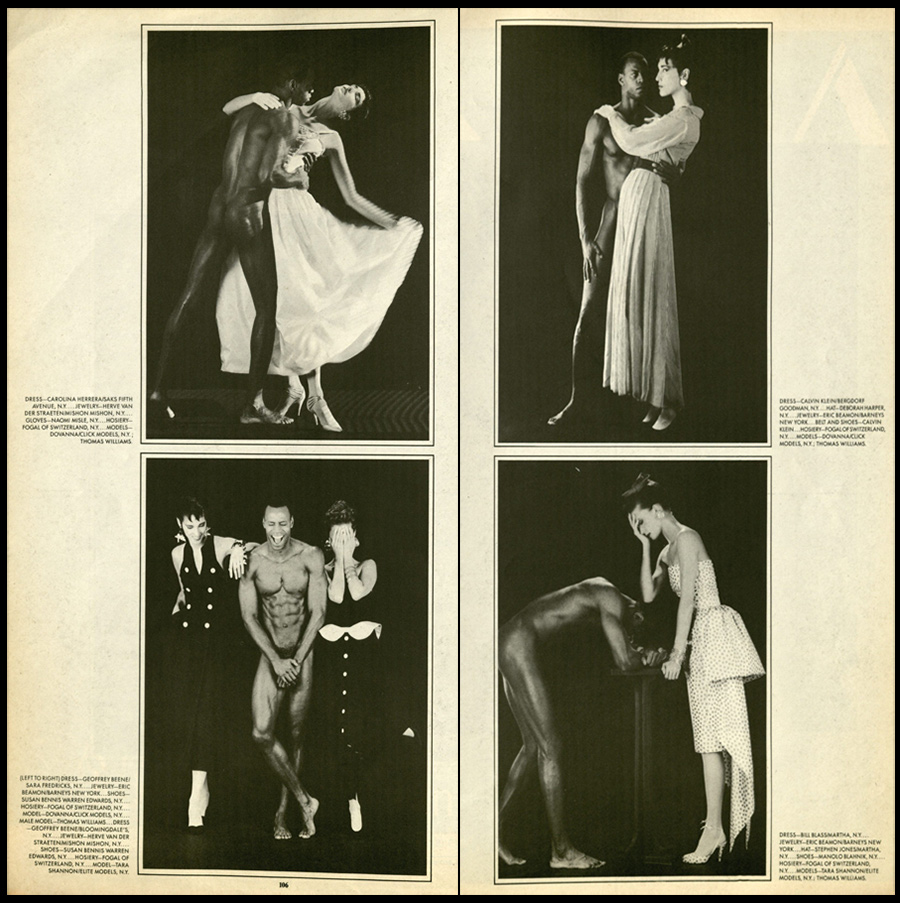

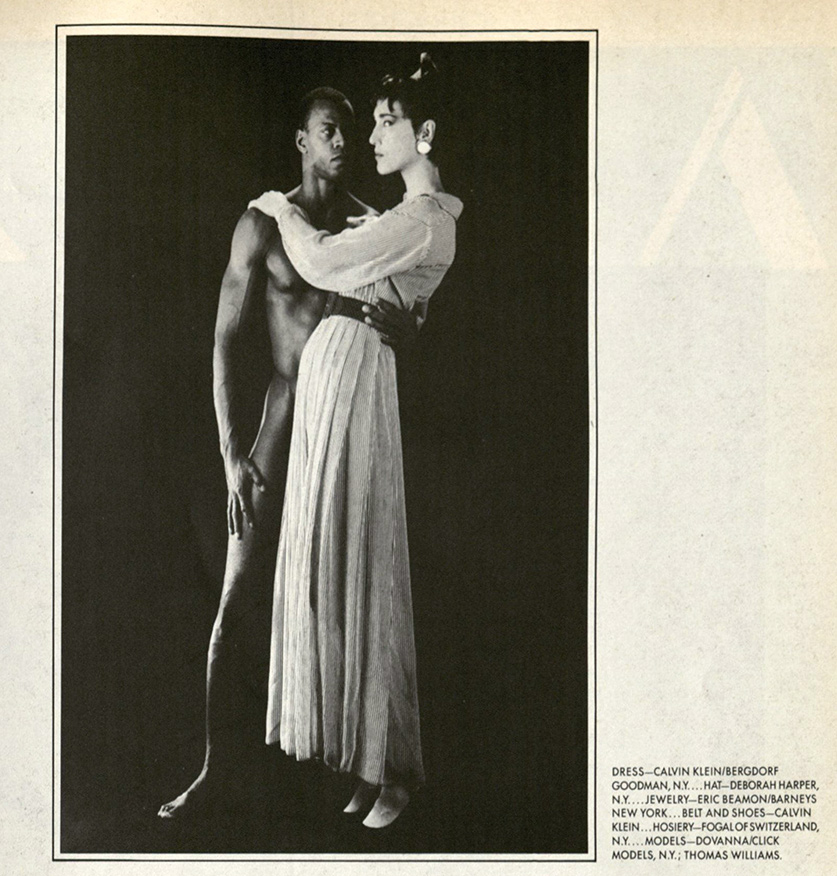

Robert Mapplethorpe photographs in a spread from Interview magazine, March 1987, in the Robert Mapplethorpe archive. Photographs © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

A professor of history at Duke University and a theorist of sexuality and gender, scholar Pete Sigal recently visited the Getty Research Institute to study materials in the Robert Mapplethorpe archive. We invited him to share his discoveries with our readers. —Editor

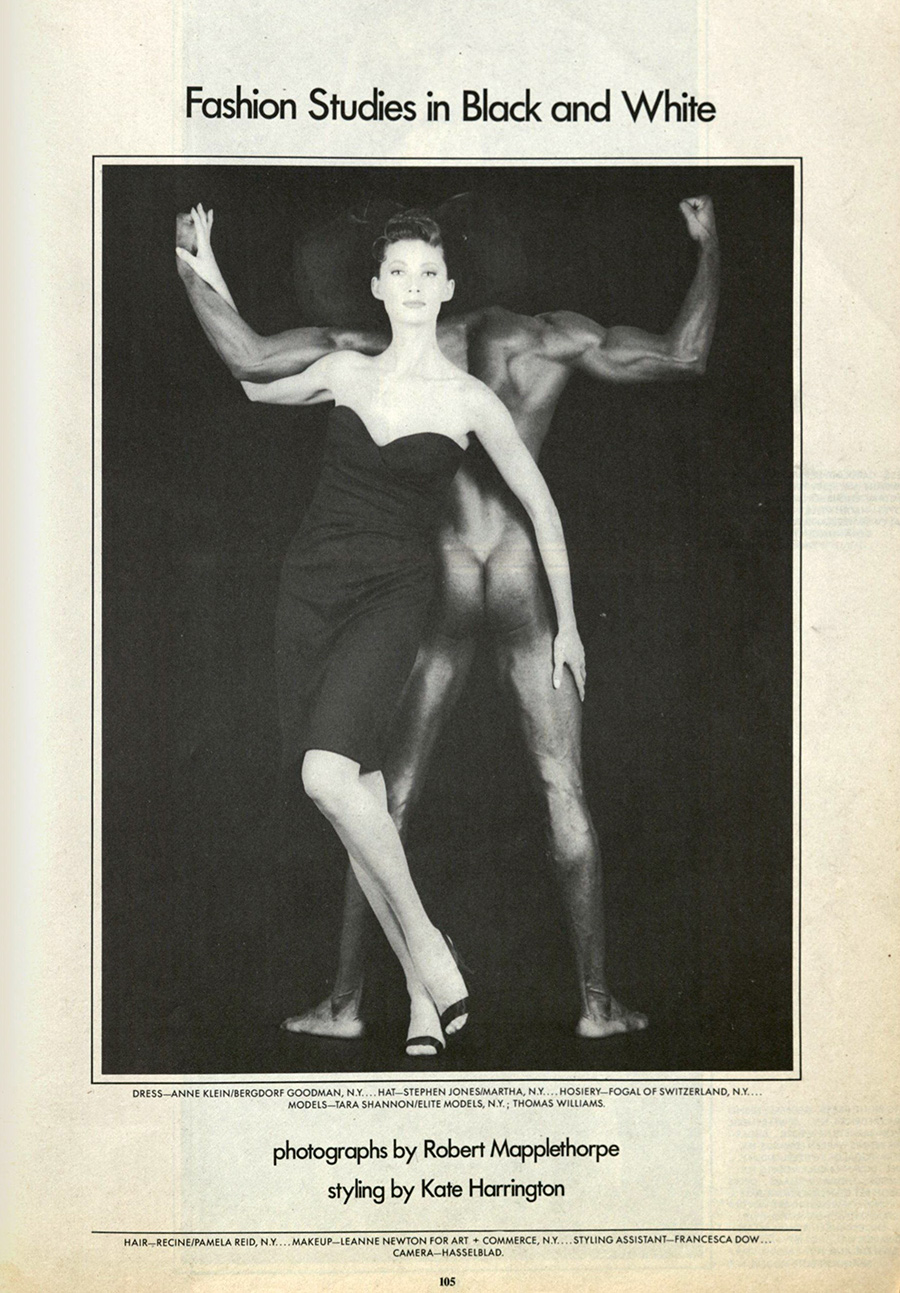

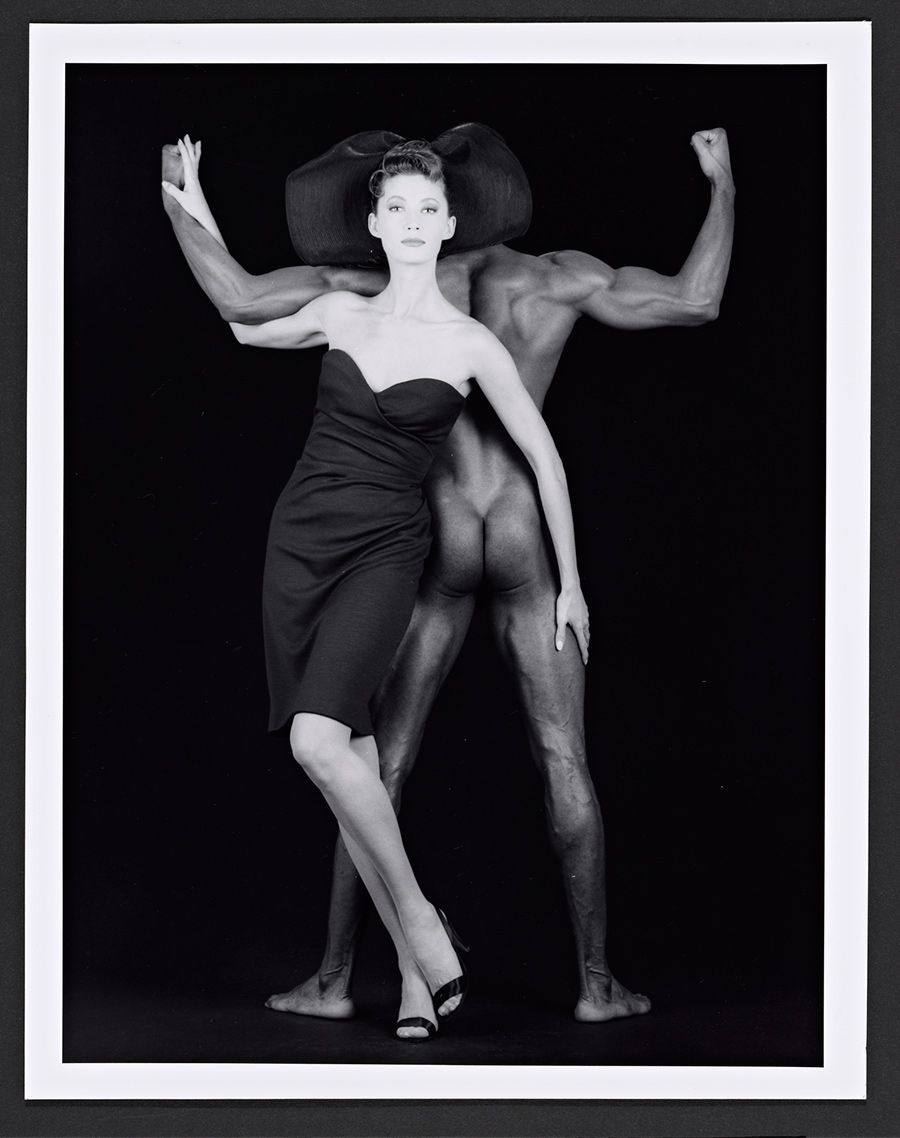

The beautiful, muscled ass of pornography star Thomas Williams greeted the readers of the March 1987 issue of Interview magazine (fig. 1). In a fashion spread advertising the clothes worn by fashion model Tara Shannon, photographer Robert Mapplethorpe challenged the magazine’s readers to see the black man’s ass as a sexual object. In doing so, Mapplethorpe not only emphasized the backside of the nude black man in comparison with the clothed white woman, but he also, as we can see in the less grainy image in the archive’s collection of non-editioned prints (fig. 2), symbolically decapitated Williams by hiding his head behind Shannon’s hat. The grainy image certainly would be seen by far more people than the fine art connoisseurs who would see the image of Williams and Shannon in a Mapplethorpe exhibit, allowing us to relate both commerce and history to Mapplethorpe’s vision.

When I entered the Getty Research Institute to examine the Robert Mapplethorpe archive, I expected to find salacious photographs and perhaps some steamy correspondence. I wanted to write about the ways in which the photographer related to his black models, and in particular to think about how he moved from the 1970s New York gay sadomasochistic scene to the portrayal of the black male body as a fetish. I found that this was only part of the story: Mapplethorpe was enmeshed in a particular time period—one in which he would portray a historical vision to an unsuspecting public.

As Jack Fritscher, publisher of Drummer magazine and one of Mapplethorpe’s lovers, reminded me in an interview a few days after I left the Getty, Mapplethorpe’s photographic and sexual activity in relation to black men was part of a very important time and place—late-1970s and early-1980s New York City—in the history of sexuality. Before concerns about AIDS became endemic to gay community life, this was a period of sexual experimentation. Mapplethorpe would sometimes pick up his models at bars or on street corners in Greenwich Village and the Meatpacking District. In doing so, Mapplethorpe knowingly documented not a timeless understanding of race and sexuality, but rather a historically situated black male body.

In the March 1987 issue of Interview, the story of a black gay man in the 1980s provides a backdrop to Mapplethorpe’s larger historical vision. Thomas Williams had been a budding actor and bodybuilder when he crossed paths with the photographer. Soon, as his images made him famous through his collaboration with Mapplethorpe, Williams began a career in gay pornography under the name Joe Simmons. While we may categorize Williams as gay because of his participation in a gay male sexual milieu in both his daily life and his career, we should note the problematic nature of such an identity category. Another Mapplethorpe model, Veronica Vera, had a sexual relationship with Williams, and indeed Williams had sex with both men and women. Yet we have no evidence that he ever identified as bisexual, an equally opaque identity category.

Figure 1: Tara Shannon and Thomas Williams photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe from Interview magazine, March 1987. Photograph © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

Figure 2: Tara Shannon and Thomas Williams, 1986, Robert Mapplethorpe. Gelatin silver print. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.20, Box 92. Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

Mapplethorpe’s collaboration with Williams in the Interview spread tells us a complicated story of the sexualized history of race. My speculative account of this story goes something like this: We begin with the models, the beautiful white woman, Tara Shannon; the lustrous Latvian woman (racially also coded as white), Dovanna Pagowski; and Williams, the masculine black man with the chiseled body. Shannon was a supermodel with an auburn mane and ivory skin, along with a tragic background. Pagowski was another successful model with a long career and a heavy partying lifestyle.

Mapplethorpe and the three models, in conjunction with stylist Kate Harrington, told a story that emanated from the racial identities of these models as well as the fashion they wished to explore. The title of the Interview story, “Fashion Studies in Black and White,” alludes to both the historical story of race and the contemporary story of fashion. In image one, we see the models intertwined. Shannon faces us, wearing a black Anne Klein dress from Bergdorf Goodman. Williams has his back to us, and he appears, as we have noted, headless. Instead of his head, we are faced with his muscular ass. We also notice that Williams flexes his muscles in his prominent chiseled arms. Shannon seductively wraps her right arm around his left, and she uses her left hand to grasp his right thigh. She places her right hand on his left fist—and he never unclenches either fist or buttocks.

Some critics have taken Mapplethorpe to task for cutting off the heads of many black men, objectifying them by picturing just the cock or the ass. Mapplethorpe, though, considered the buttocks, the genitals, and other body parts as effective representatives of the subject in portraiture. Still, his portraits, mostly of white people, were quite traditional, emphasizing the face. One may say that the images of black men that emphasized genitals, buttocks, and even many other body parts, like the images of gay sadomasochism, were intended to objectify. They force us to face the process of objectification, something we can see in Mapplethorpe’s playful positioning of Williams’s head behind Shannon’s black hat.

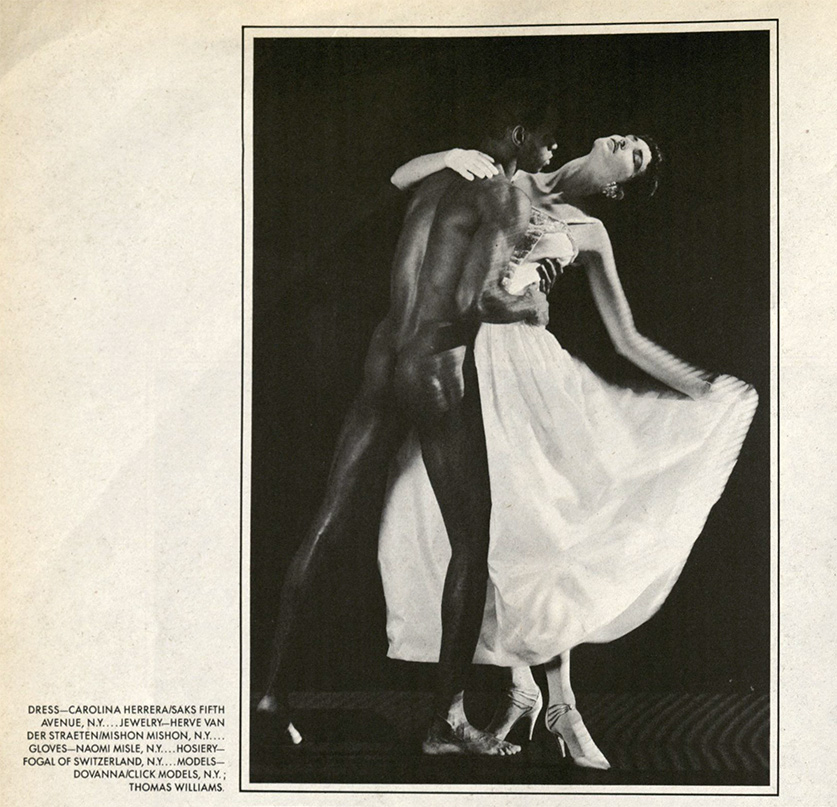

The next image in the Interview spread further emphasizes this point (fig. 3). In this photograph, Williams, still naked, holds Pagowski up and the two appear to dance. Pagowski wears a white Carolina Herrera gown from Saks Fifth Avenue. Williams remains naked. We see Williams’s head, though the photograph casts a shadow over him to emphasize once again his back and buttocks. The dancing Pagowski swoons in the arms of a naked black man who stares intently at her. Because of his naked objectified body, Williams catches our attention in the photo, despite the fact that we are meant to focus on the clothes.

A third photo shows the three models together (fig. 4). Apparently someone has told a joke as all three laugh, Pagowski and Williams with closed eyes, and Shannon with her hands covering her face. The background to the picture is so dark that the black outfits seem to fade; we can barely see them—despite the fact that the ostensible purpose of this spread is to sell these outfits. Williams still wears nothing, and the photograph pictures full frontal nudity…but, wait, his hands cover his crotch (Could this be the joke? Are the three of them laughing at Williams’s big black cock?).

Figure 3: Dovanna Pagowski and Thomas Williams photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe from Interview magazine, March 1987. Photograph © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

Figure 4: Dovanna Pagowski, Tara Shannon, and Thomas Williams photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe from Interview magazine, March 1987. Photograph © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

In addition to making us think about what remains hidden under his hands, the picture of Williams emphasizes his chest and abdomen. Williams has a body that one would expect only from a professional bodybuilder. Both women touch Williams, Pagowski leaning on him with her left arm over his shoulder, Shannon leaning on him from the other side, with her right arm touching his left. Perhaps most importantly, we can consider the gaze—all of them have their eyes closed; they do not want to see, nor do they want us to see, the black penis. Between the clothes fading into the background, the closed eyes, and the hidden phallus, we wonder what else Mapplethorpe and the models hide from us. This image continues to objectify Williams and also teases us—we want to see what comes next.

The fourth photo (fig. 5) obscures much of Williams’s body, perhaps to emphasize his face. We see his muscular right arm and pectoral, as well as his upper leg, while his lower leg fades into the black background. Most prominent here is his glare. This is the only time in this entire spread that we see his eyes, and he appears angry with Pagowski. She, on the other hand, wearing a black and white striped Calvin Klein dress from Bergdorf Goodman, gives off a coquettish look. He has his left arm wrapped around her waist and both her arms grasp his shoulders. In this photograph, we begin to see Williams’s desire. With emphasis shifted from body to face, we encounter the stereotype of the intensity of black masculinity.

A final image (fig. 6) has Williams bent over a pedestal, hiding his head, perhaps in shame, and we can see the right side of his body. His hunched look could enable anal penetration—and his ass falls out of the frame. Shannon, wearing a Bill Blass dress, has her hand against her forehead. Perhaps he has told her something devastating; perhaps this relates to his anger with Pagowski. Among Mapplethorpe’s male figure studies in the archive, we find a similar image of Williams (fig. 7), but with Pagowski nowhere to be found. The image emphasizes his muscled body, but in context we witness his despair. Perhaps the story concludes with trouble as the three part ways.

_______

“The texture of black skin is something that excites me photographically maybe as well as other ways . . . There was a reason that bronzes are bronze. The subtleties of skin tone somehow are more refined.”

—Robert Mapplethorpe

In a 1984 lecture that Mapplethorpe gave to Camerawork in San Francisco (a recording of which is housed at the Getty), the photographer asserts his sexual and photographic excitement in relation to black skin. He also gives black skin a timeless quality, but he of course knows that he photographed black men (and a few black women) at a particular time and place, when he could act out his desires toward black skin.

Figure 5: Dovanna Pagowski and Thomas Williams photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe from Interview magazine, March 1987. Photograph © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

Figure 6: Tara Shannon and Thomas Williams photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe from Interview magazine, March 1987. Photograph © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

Figure 7: Thomas On A Pedestal, 1986, Robert Mapplethorpe. Gelatin silver print. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.20, Box 92. Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

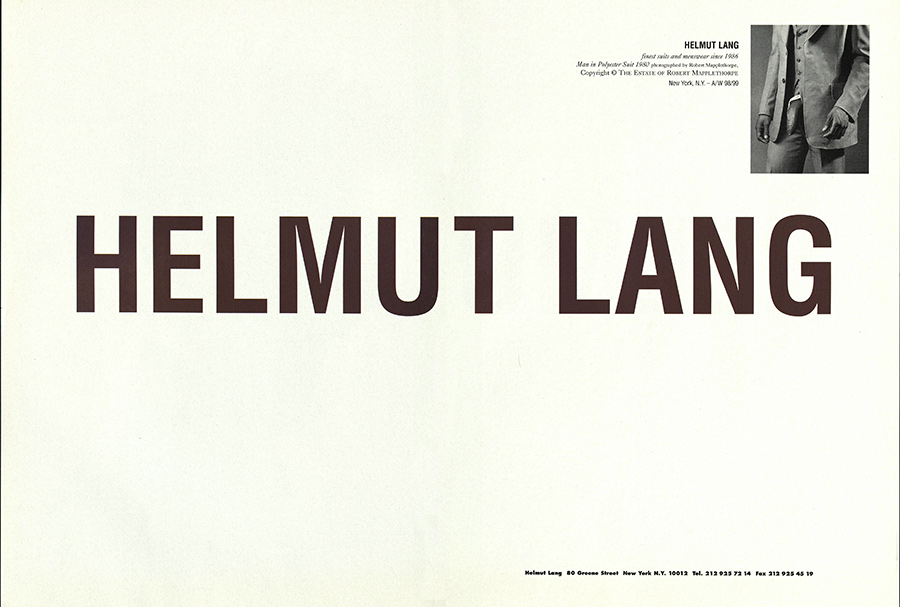

In his photographs of black men, Mapplethorpe does not hide his attraction to big black cocks. He also, though, shows an appreciation for the history of race and an attraction to black masculinity and subjectivity in many forms. Even his most famous photograph of a big black cock, Man in Polyester Suit, warrants a historical analysis, as we can see from its place in an advertisement for fashion designer Helmut Lang (fig. 8). As the cock emanates from an open fly in the suit pants, the photograph suggests that, if we bother to look, we find a surprise underneath the suit. Shockingly, in the late 1990s, Lang chooses this image as one to advertise his suits with the caption, “Helmut Lang, finest suits and menswear since 1986.” One can interpret this caption in many ways, but the point here is that, for the fine fashion designer, the black phallus, a historical figure that has at once evoked fear, desire, disgust, pleasure, pain, and exoticism, became a sign of success based on the designer’s avant-garde status in his association with one of Mapplethorpe’s most controversial photographs.

The model for this picture, one of Mapplethorpe’s lovers, asked not to have his name or face associated with any shots of his penis and wore his own suit to the photo shoot. In other photographs of this model, we can witness the significant affection that Mapplethorpe undoubtedly felt for him. In thinking about the complexity of Mapplethorpe’s relationship with black men, we should also note that the archive houses two letters from the model to the photographer (from a period after the end of their relationship), implicitly threatening Mapplethorpe. Photographer and model conspired to shock the audience, exoticizing and eroticizing black masculinity at the same time as they force us to confront our fantasies and fears in relation to the black phallus.

When we discuss Mapplethorpe’s very stylized images of black men, we tend to see him as an individual who loves certain things about black male anatomy, most particularly, the big black cock. However, we tend to forget that the photographer, in collaboration with his models, had a vision that emanated from the time and place in which they lived. That vision related to the history portrayed during the time—Mapplethorpe had recently watched, along with Jack Fritscher and a theater primarily full of African Americans, the movie Mandingo, which portrayed interracial desire in particularly lurid ways.

The historical vision portrayed in the Interview spread relates in a similar manner to a history of interracial desire and stereotypes. Williams becomes, in this imaginary universe, the black stud, full of hypermasculinity. At the same time Williams never wears clothes in a spread designed to sell clothes. And we first meet him with his back towards us and his head missing from the picture. In fact, we only see his open eyes once, in an image where he glares menacingly at a white woman. Williams becomes imagined as a being full of illicit interracial desire, seduction, and sexual pleasure, in which he becomes involved in a ménage à trois with two white women. In the end we see him dejected, in a submissive position with his ass running off the edge of the frame. The abjection of Williams, his muscular body, hidden penis, and prominent, perhaps penetrated, ass, becomes the key story, with two white women playing important roles that could, historically, get the black man lynched.

Mapplethorpe, Williams, Pagowski, and Shannon tell us a story with historical resonance, a story of lust, anger, and violence. They aggressively emphasize the connections between fantasy and fear in the cultural portrayal of black men. When we buy the clothing advertised in “Fashion in Black and White,” Mapplethorpe tricks us into subconsciously learning about a history of race relations in the United States and beyond, a history that one can explore in the Mapplethorpe archive at the Getty.

Figure 8: Helmut Lang advertisement. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.20, Box 139, folder 7. Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Photograph © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Design © Helmut Lang. All rights reserved

_______

Explore the Robert Mapplethorpe archive further online, in the recently published book, and in this podcast interview with Research Institute curator Frances Terpak.

If you have used Getty collections in your own scholarship and would like to share your work with the readers of The Iris, please contact the editor.

See all posts in this series »

Interesting take on these images and certainly Mr. Sigal’s reminder that they are situated at a certain place and point in time which is most important. NYC in the 60s, 70s & 80’s was a raw urban environment and one that was experimental in many ways-racially, sexually, cross-racially/sexually, along with the drugs and other mind-altering substances that became available. There was very much a freedom to blur all societal borders and boundaries for both genders, especially for women who for the very first time could enter into many heretofore banned public spheres where only males had trod previously, particularly within the gay world.

I see these fashion pictures as a both/and attempt of gender-blurring; fashion as sexualization of the dressed and nakedness as sexualization of the undressed, juxtaposed. The women are covered, but perhaps secretly wish they were free to be naked as Thomas, but are caught in their own paradigm of stereotype as the properly-dressed, virginal female in her own role of being objectified on the page in the latest mode as Thomas is in his role of objectified, black, sexualized male who perhaps secretly wishes to be covered as we see alluded to in the fourth picture when his hands cover his genitals. In addition, that last image,Thomas On A Pedestal, has a tonal quality of his skin that lightens the color of his black skin to almost white. Could this be another play on the black/white theme?

In addition, Mapplethorpe as the hidden voyeur-photographer-participant has posed Dovanna, Tara and Thomas within the frame of his camera and chosen those images that were used for the magazine.

If this series was reshot today, what might change within the context of these subjects as objects and in the eye of the photographer? Would the photographer jump in for a ‘selfie’? I wonder!