The sound of bells ring as the screen fills with blue. As they echo and fade, Derek Jarman’s voice begins, “O blue come forth, O blue arise, O blue ascend, O blue come in.”

Blue (1993) was Jarman’s final film before he passed away from AIDS just a year after its creation. For 79 minutes, viewers experience a permeating sensation of blue, specifically “International Klein Blue” or IKB (but more on that later!). This monochrome film plays with a sound collage of visceral and poetic narratives spoken by Tilda Swinton, Nigel Terry, John Quentin, and Jarman himself. Although simplistic in its visuals, the experience of the film goes far beyond the surface.

When I joined the Getty as the graduate intern for public programs this fall, I found out our first major project would be an outdoor screening of Blue. The event occurs as the museum considers all things magical and mysterious about color with the exhibitions The Art of Alchemy and The Alchemy of Color in Medieval Manuscripts.

Admittedly, I had never seen the film. And, initially I found it puzzling that a contemporary film was suggested as a public program alongside exhibitions that focus primarily on people of the Middle Ages and their interest in alchemy in art. I wondered: Where is the connection between medieval alchemy and a gay male artist in the late 1980s and early ‘90s dealing with HIV and AIDS? So I did as any self-respecting museum programmer would do: I dove deep into research on the man, the movie, and the first question that came to my mind—why blue?

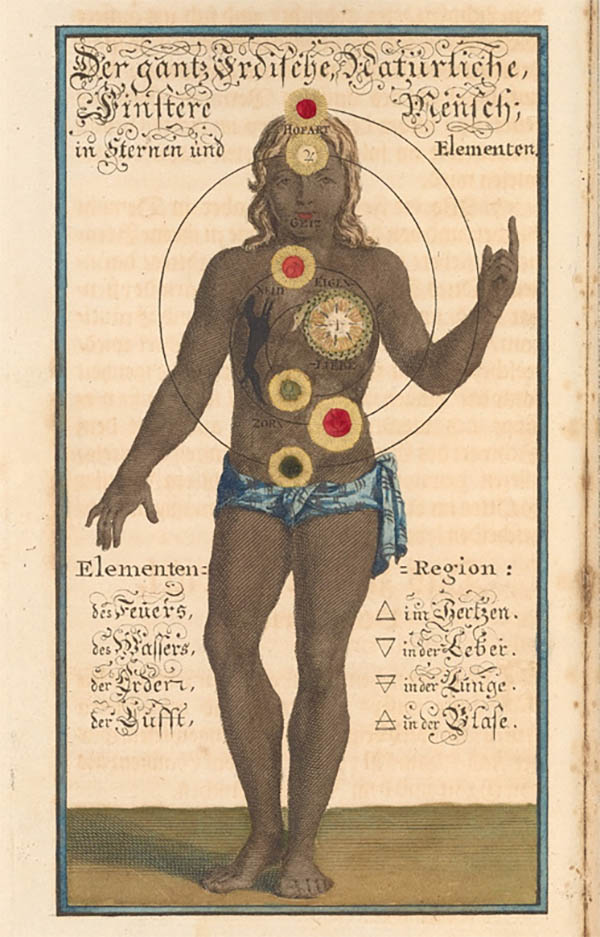

The Entire Earthly, Natural, and Dark Man, 1723. From Johann Georg Gichtel, Theosophia Practica [Practical Theosophy] (Leiden, 1723), pl. before p. 25. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2611-134).

Jarman was interested in the spiritual and the occult throughout his artistic oeuvre. He saw art as a form of alchemy, which is said to transform individuals spiritually and mentally through channeling creative energies within nature and the human mind. In Chroma: A Book of Color, he discusses his experience with alchemy, describing it as a “quest for the philosophic and incorruptible gold,” and a “journey of the mind, the metal the mirror of the saviour.” He identified greatly with the magic experienced through the process of artmaking.

Jarman’s Blue exemplifies the transformative and creative energies found in the work of the alchemical process, particularly those in the stage of the “journey.” As described in Astrology, Magic, and Alchemy in Art, the journey is “one of the more widely used metaphors to describe the unfolding of the alchemical process and the achievement of the goal, which is the integration of the psychic, energetic, and corporeal principles that preside over the life of man and the universe.”

Just as people in the Middle Ages turned towards alchemy as a way to make sense of the world and feel control over the creation of materials, Jarman, in a way, did the same. Considering that the film’s primary purpose was to convey Jarman’s experience of his life with HIV and AIDS, it makes sense that he took artistic inspiration from the spirituality of alchemy in order to comprehend and confront the situation life had handed him.

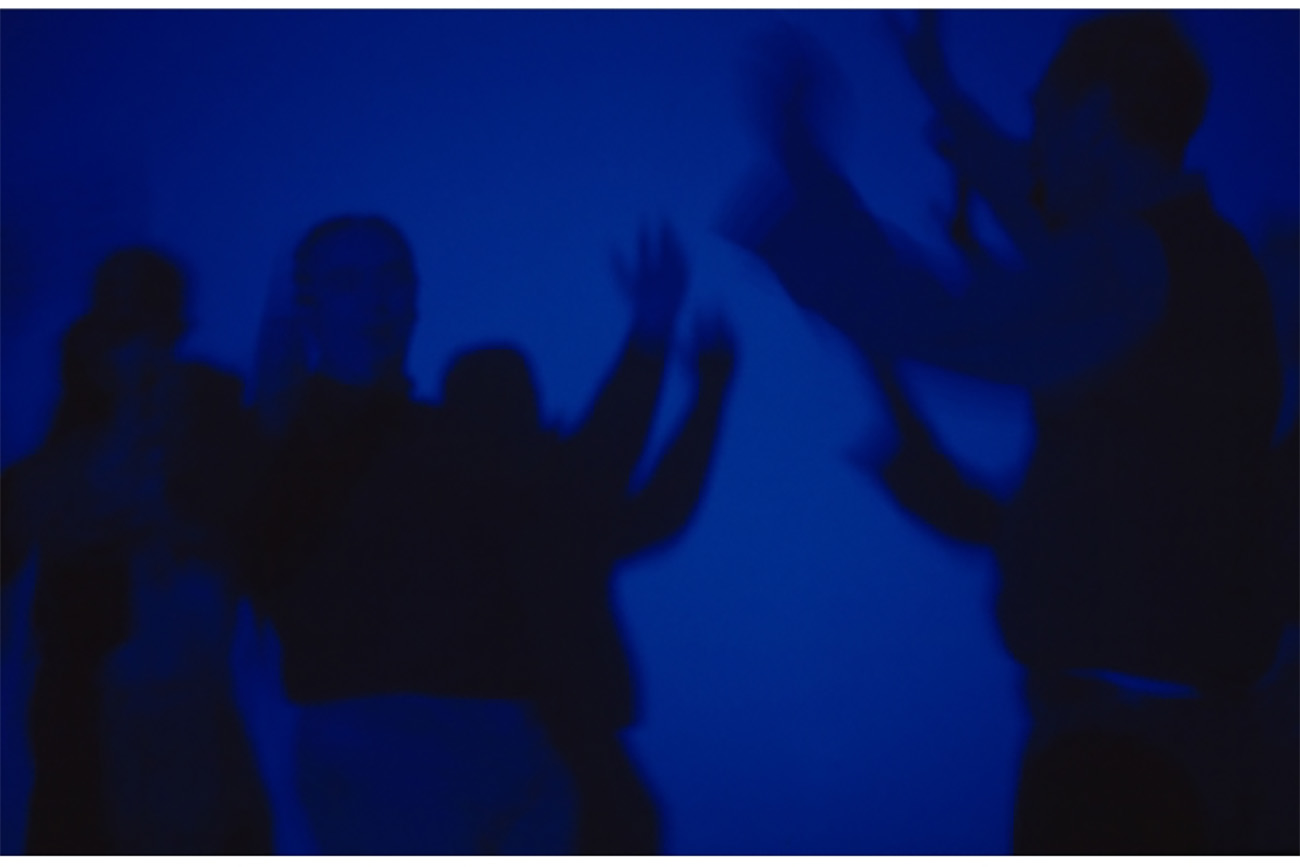

Still from Derek Jarman’s Blue. Photo: Liam Daniel © 1993 Basilisk Communications Ltd.

Jarman was diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1986. This was a moment in history in which the LGBTQ community was dealing with not only sickness and death from AIDS, but was fighting for exposure and help with the epidemic. At the end of Blue, Jarman says that “no ninety minutes could deal with the eight years HIV takes to get its host. Hollywood can only sentimentalize it.” Therefore he made a bold choice to remove all visual representations and instead saturate the screen with pure blue. And, again, why blue?

One reason: when Jarman fell ill, he was not only grappling with the reality of approaching death, but he was also dealing with the loss of his eyesight. Due to his medications, he actually began to slowly see the world through a filter of blue.

But, there’s more to the answer than that. As I mentioned earlier, this isn’t just any blue. Specifically, it’s International Klein Blue (IKB), a blue patented by Yves Klein, a renowned French painter who was a great influence on Jarman. After viewing Klein’s IKB 179 (1959) at the Tate Gallery in 1974, Jarman was immediately inspired by it, as well as the rest of Klein’s monochromatic paintings. The influence of Klein’s work is clear in Jarman’s entire artistic oeuvre through their shared interest in the void, the spiritual, and the power of color.

Still from Derek Jarman’s Blue. Photo: Liam Daniel © 1993 Basilisk Communications Ltd.

The IKB used in Jarman’s Blue can be directly connected to Klein’s own meaning of color and process as an artist. Like Jarman, Klein was greatly interested in the immateriality of the color blue and its association with the sky. A follower of Rosicrucianism, a philosophy associated with the occult, mysticism, and the metaphysical laws governing the universe, Klein saw color as pure and spiritual.

Klein and Jarman both used blue as a means of escape, coping, and often, peace. In all of the various pursuits of the spiritual and occult within his art, Jarman, like Klein, utilized his artistic process as a means of transcendence. Blue shows us a man longing for control, escape, and a slow acceptance of his fate.

Although the film provides no visual narrative—the Walker Art Center has even called it a “Film without Film”—the actual experience of the film does suggest transformation. The experience of that deep IKB is in no way stagnant; it changes quickly throughout the film thanks to the narrative offered by sound. I experienced moments of peace as bells chimed, but felt accosted by the sounds of bustling night clubs and medical equipment. Sounds of the hospital fill the space in a way that is just as overpowering as the blue shining on you as you take in the reality of his looming death.

Still from Derek Jarman’s Blue. Photo: Liam Daniel © 1993 Basilisk Communications Ltd.

For Jarman, there was no need to show real images of the hospital, his community, or himself in order to reflect on the experience of HIV and AIDS. Indeed, the anonymity allows the film to incorporate the experience of the LGBTQ community at large. The blue changes meaning and experience as viewers are led through Jarman’s illness as well as his transcendence into the acceptance of death for himself and for many of his friends and loved ones.

The motivation to practice alchemy is one that many can relate to: a desire to understand the world around us and to find meaning and control over your experiences of nature and the universe. These desires within the work of alchemists and artists such as Klein and Jarman, although seemingly mystic and magical, are actually quite universal. They are what allow the experience of a film like Blue to touch any visitor who lets themselves to step into it.

_____

Derek Jarman’s Blue will be screened on the Garden Terrace at the Getty Center on Friday, November 4, 2016, at 7:30 p.m. This event is free, but reserving tickets in advance is recommended.

Comments on this post are now closed.