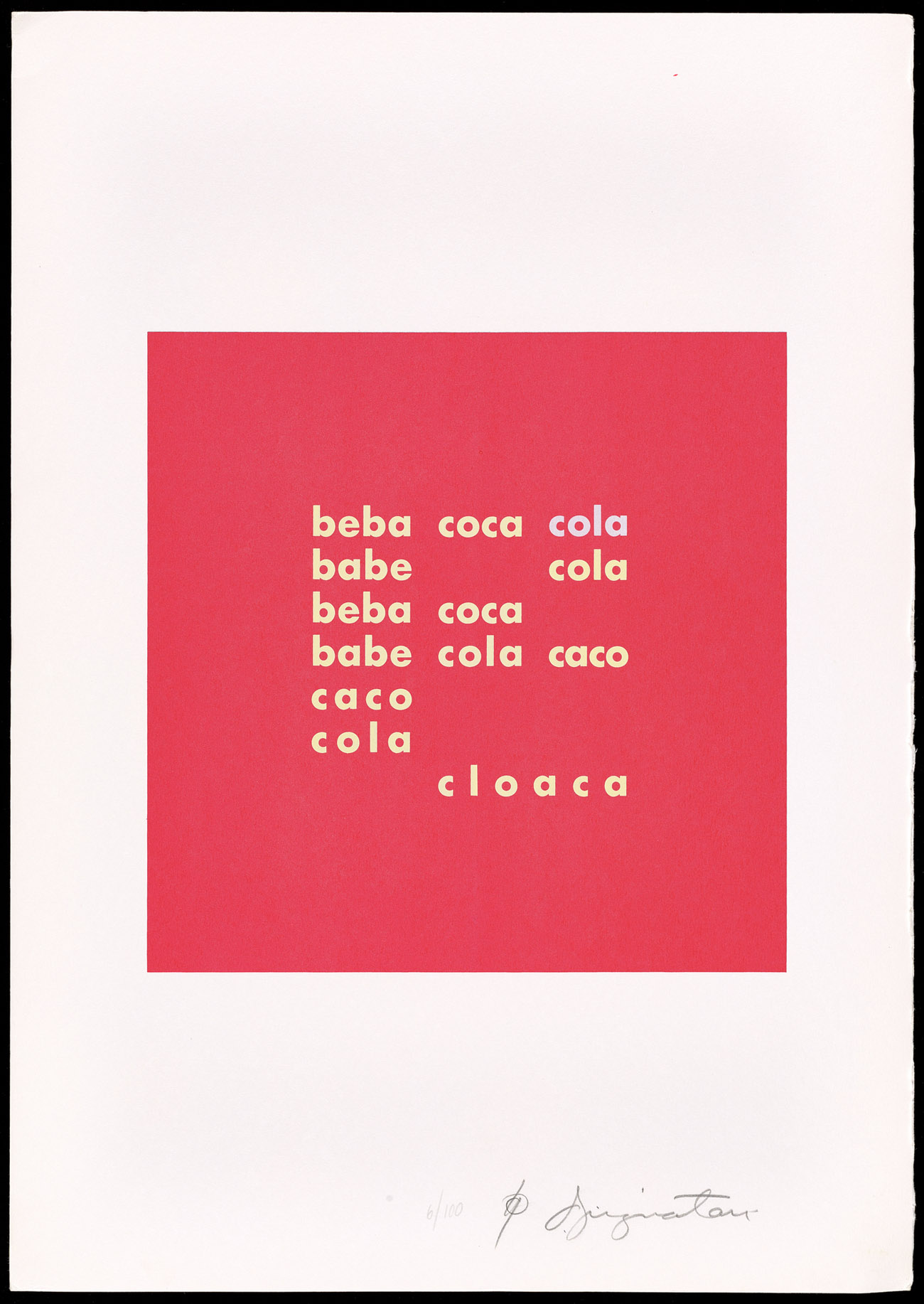

Beba Coca Cola (Drink Coca Cola), 1957, Décio Pignatari. Screen print from Poesia concreta in Brasile (Milan: Archivio della Grazia di Nuova Scrittura, 1991). The Getty Research Institute, 45-13. Courtesy of the Estate of Décio Pignatari

“Drink Coca-Cola!” Who hasn’t come across this slogan before? No matter what corner of the world you live in, these words have likely reached you. This was even true in the 1950s when Coca-Cola commercials first reached a global audience and were translated into as many languages as possible. The Brazilian poet Décio Pignatari turned this phenomenon into art, using the Portuguese version of the slogan to create the concrete poem Beba Coca Cola.

Reproducing the red and white of the Coca-Cola label, the work functions as a sort of anti-advertisement. The poet deconstructed the famous slogan through the phonetic transposition of its three words—beba, coca, and cola—and their layout in graphic space. The act of reading the poem becomes a journey: the reader travels from the flavor of Coca-Cola, to the unpleasant taste of glue (cola), to the sharpness of shards (caco), to the disgusting odor of cesspools (cloaca). Through an inverted alchemical process, Pignatari’s wordplay transforms Coca-Cola gold into garbage, thereby critically commenting on the incipient globalization of his time.

Pignatari and other concrete poets were primarily united through their common approach to poetry, which the American poet Mary Ellen Solt articulated as: “All definitions of concrete poetry can be reduced to the same formula: form = content / content = form” (Concrete Poetry: A World View, p. 13). But they were also deeply engaged in formulating an open, boundary-less worldview, exploring varying perspectives on globalization, transnationalism, and the universality of language. This mentality was reflected in the concrete poetry movement itself, which was international in scope and drew in poets from around the world. By playing with language, manipulating graphic space, and interacting with each other’s work, the concrete poets delved into these themes in novel ways on a global scale.

Augusto de Campos embraced the dynamics of postwar global interconnectedness with a more optimistic approach than his colleague Pignatari. In the poem Cidade/City/Cité, the leading Brazilian poet played with the word city in three different languages—Portuguese, English, and French—by using it as a key to decipher a long line of text formed by prefixes. By attaching the suffixes cidade, city, and cité, new words are formed: for example, capa becomes capacity (capacidade and capacité), and simpli becomes simplicity (simplicidade and simplicité). These words share the same meaning in all three languages, making this a truly transnational visual work. It’s not by chance that city is the key to this digital poem, as de Campos shows how the metropolis is central to our understanding of contemporary global exchange.

Forsythia, 1965, Mary Ellen Solt. From Flowers in Concrete (Bloomington: Fine Arts Department, Indiana University, 1966). The Getty Research Institute, 94-B19512. Gift of Susan Solt / Courtesy of the Estate of Mary Ellen Solt

In addition to playing with language, concrete poets manipulated graphic space to thwart culturally ingrained ways of reading. They challenged the traditional Western mode of reading lines of text from left to right by modifying the graphic space of the page and constructing recognizable images out of letters and words. One ingenious example is the visual poem Forsythia by Mary Ellen Solt. Each letter of the word Forsythia forms the branches and roots of the flowering plant. The word also operates as an acronym for “Forsythia Out Race Spring’s Yellow Telegram Hope Insists Action,” a telegrammatic sentence that conjures up the role of the forsythia as a harbinger of spring.

Vite (Fast), 1961, Henri Chopin. From Le dernier roman du monde: Histoire d’un chef-occidental ou oriental (Wetteren, Belgium: n.p., 1970). The Getty Research Institute, 93-B2246. Courtesy of Brigitte Chopin Morton

Like Solt, the French poet Henri Chopin explored how words can be shaped to reference their meaning. Defined by the author as a “graphic poem for a kite tail,” Vite consists of only one word that repeatedly appears on the paper in columns of varying length to create the visual form of a kite tail. Vite, which means fast, also visually emphasizes how a kite speedily flies through the sky.

Another layer of the multisensory experience of concrete poetry is its vocalization. Listen to the performance of this poem and hear how the word Vite is repeated at different speeds and intonations. Like de Campos and the Austrian poet Ernst Jandl, Chopin understood the performative and sonic dimensions of language to be central to the experience of concrete poetry.

Paper Pear, Ian Hamilton Finlay. From 6 Small Pears for Eugen Gomringer (Edinburgh: Wild Hawthorn Press, 1966). The Getty Research Institute, 92-B547. Courtesy of the Estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay

While concrete poets broke down boundaries by playing with language and form in unconventional ways, they also participated in a borderless world by engaging with each other’s work despite being spread across the world. The Scottish Finlay created the small book 6 Small Pears for Eugen Gomringer in homage to the Bolivian-born Swiss concrete poet.. The two poets were friends and colleagues, and their international dialogue is communicated in subtle ways in the poem Paper Pear.

For example, Finlay referenced Gomringer’s concrete poem Ping Pong through the alliterative use of the letter P in Paper Pear. He also organized the words on the page in a zigzag form, directly mimicking Gomringer’s own design. Unlike Gomringer, who used only black text, Finlay employed blue for consonants and red for vowels, thereby creating a playful visual dynamic.

Whether connecting across borders, like Finlay and Gomringer, focusing on globalization and transnationalism, like Pignatari and de Campos, or exploring the universal qualities of language and image, like Finlay and Solt, the concrete poets found innovative techniques to convey their boundary-less worldview through words.

_______

Learn more about the commonalities and differences among artists in the international concrete poetry movement at “Paper Pear Paper”: Charting the Course of Concrete Poetry, a panel discussion at the Getty Center on Thursday, April 6, 2017, at 7:00 p.m. Book a free ticket here.

For beautiful concrete poetry, I always loved “Le Jet D’Eau”, an anti-war poem by the Italian-French poet, Guillaume Apollinaire. It’s in French, of course. The poet laments the loss of his friends in WWI.