Stained glass conservator Léonie Seliger explains why these 800-year-old paintings in light are “completely, unashamedly new”

Six monumental stained glass windows from Canterbury Cathedral depicting the ancestors of Christ take pride of place in the exhibition Canterbury and St. Albans: Treasures from Church and Cloister. Léonie Seliger, director of the Stained Glass Studio at Canterbury Cathedral, recently visited the Getty to oversee the installation of the glass, and offered a surprising explanation about why these works of medieval painting are so thoroughly modern.

Léonie Seliger (left) and Laura Atkinson, conservators from the Stained Glass Studio at Canterbury Cathedral, at the entrance to the exhibition at the Getty Center

What’s special about these windows from Canterbury Cathedral?

These were cutting-edge works of art for their time. This isn’t something stale; it’s modern art.

When you see really good art—regardless of the age—if it was really modern at the time, it still has that zing, that feeling of excitement you get from art that is completely, unashamedly new. This is what these windows are.

What’s so modern about them?

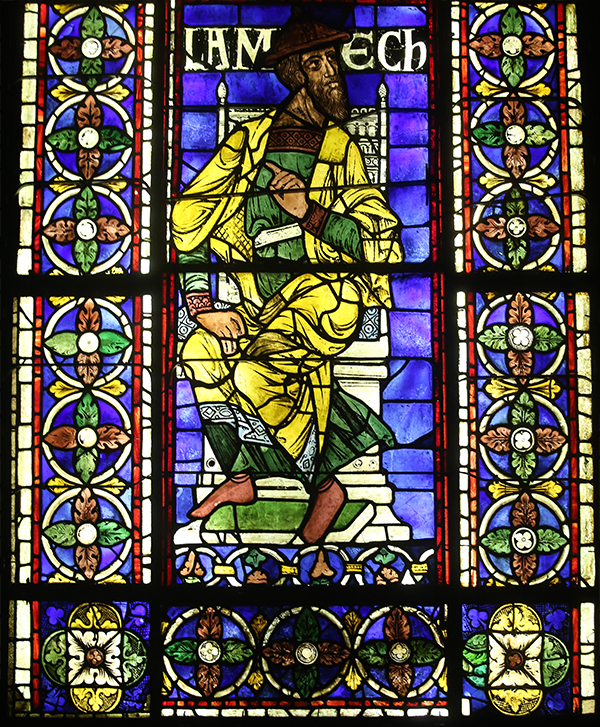

The boldness. The rhythm of the brush lines. The trace lines in the drapery. There is no fussiness about this painter—he just put them on confidently, without taking time to think about it. It’s very gutsy work. I’ve often thought about this being an early incarnation of Jackson Pollock.

Lamech, from the Ancestors of Christ Windows, Canterbury Cathedral, England, 1178–80. Colored glass and vitreous paint; lead came. Courtesy Dean and Chapter of Canterbury

Abstract Expressionism in the Middle Ages?

Of course they didn’t have these concepts consciously. But artists of all ages have worked in that idiom, with abstract appreciation of form and shape and rhythm and graphic impact. The shape is a figure, but it’s made good art by the confident handling of the abstract qualities.

Also, these were made at speed. It only took about ten years, if that, from start to finish to make all these figures. They certainly didn’t hang about with these—they painted them, then they were leaded up and put up. No time for being precious.

It was also a Zeitgeist of the time. Coming out of the Romanesque period into the Gothic period is a very exciting time in art.

Installation view of stained glass windows from Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury and St. Albans at the Getty Center. Stained glass courtesy Dean and Chapter of Canterbury

What caused this artistic break from the past?

Canterbury Cathedral had just had a very traumatic twosome of events. First they had the murder of the archbishop in the Cathedral [Thomas Becket, in 1170] and four years later the cathedral burned—the cathedral they’d just rebuilt in the 1130s, ’40s, and ’50s, which they absolutely loved.

So this is a community in shock. But at the same time, the miracles begin to happen. And the pilgrims come pouring into Canterbury leaving money, and the Cathedral is sitting on that fund. They decide they are going to make something really positive and forward-looking out of this; to celebrate rather than go into a deep funk. I think it’s wonderful.

Tell us about the artists who made the glass.

We know that some of these glass painters—at least the masters—worked in France. This is the time when the big cathedrals are beginning to be built, with ever-bigger windows, and these people are at the top of their profession. They are in huge demand. And they would have been quite able to negotiate good terms.

The sheets of glass would have been made in France, packed in straw and into baskets, and shipped in barges across the Channel to England. Making the windows—cutting the individual pieces, painting them, firing them, and leading them—would have been done mostly on site next to the building. It’s nearly always been a different set of skills to make the glass sheets and then to make the glass windows out of those sheets.

What should we know when we look at the stained glass in the gallery?

The windows were originally installed much higher up, about 60 feet above you. They weren’t necessarily meant to be seen this close. So they have a monumental breadth of brushstroke, and the forms are impressive and expressive, with big gestures to be seen and read from a distance. The elongation of the figures [of the Ancestors of Christ] is partly because you’d see them with foreshortening from the ground of the church.

Give us one last tip, something else we might not know by looking.

The figures and their ornamental border panels were divorced about 200 years ago when the figures were put into another window in a different part of the church, while the panels were left. It’s a wonderful moment for us to see them back together. They are brothers and sisters getting to see each other after two centuries.

They were made for each other, the ornament and the figure. There is a common handwriting, a common design language between the two.

Lamech border with rosettes, flowers and circles (detail), 1178–80, attributed to the Methuselah Master. Colored glass and vitreous paint; lead came. Courtesy Dean and Chapter of Canterbury

See the windows from Canterbury, paired with pages from the St. Albans Psalter, in Canterbury and St. Albans: Treasures from Church and Cloister at the Getty Center through February 2, 2014.

Comments on this post are now closed.