Installation view of Spectacular Mysteries: Renaissance Drawings Revealed at the Getty Museum. Photo: Tristan Bravinder

Though it may be hard to imagine, the roles of a curator and a detective have much in common. Both follow clues and evidence in an attempt to uncover the truth behind a mystery. While a detective seeks the truth behind a crime, a curator seeks truth that leads to new insights in art history.

A curator’s clues take the form of artworks themselves, as well as related archival materials and documentation. These can be plentiful for curators working with artworks that enjoy centuries of documentation. Old master drawings, however, generally lack extensive documentation—and so provide a tough subject.

Drawings can also be particularly challenging to study because a single artist can create hundreds, even thousands, of them during his or her lifetime. Drawings are made for a number of reasons, sometimes as preparatory materials for other artworks (such as paintings or sculptures), and sometimes as finished works of art in their own right. Unlike finished paintings, drawings are rarely signed; there can be little evidence of who made them, which complicates the process of correctly attributing them to their makers.

In addition to all this, drawings are created on fragile materials like paper and were never intended to last hundreds of years. It’s quite a miracle that any drawings have survived from past centuries at all.

“In some ways, every drawing has a mystery,” says Julian Brooks, the curator behind the exhibition Spectacular Mysteries: Renaissance Drawings Revealed at the Getty Center through April 28, 2019. “This show is a look behind the scenes of how we, as curators, investigate these drawings. It shows the detective work in establishing who these drawings were by, or what purpose they serve.”

Brooks walked me through the exhibition, sharing with me the types of mysteries he faces in his day-to-day work.

A Revealing Inscription

Sometimes a drawing’s provenance, the history of who owned an artwork, helps us better understand it in the present day. This is the case with this exquisite work once owned by Giorgio Vasari.

Study for the Head of Saint Joseph, about 1526–27, Andrea del Sarto. Red and black chalks, 14 3/4 × 8 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.73. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Vasari was a prolific artist, art collector, and art historian in Italy during the Renaissance. He is responsible for much of what we know about artists of this era thanks to his book The Lives of the Artists, in which he documented and profiled such artists as Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, and Botticelli. With meticulous attention to detail, Vasari inscribed the name of the artist on the borders of the drawings in his collection. Finding this border inscription on the drawing Study for the Head of Saint Joseph is good evidence that the sheet was drawn by the man who was Vasari’s teacher, Andrea del Sarto.

A Mysterious Notation

Sometimes, though, inscriptions don’t necessarily help to get to the truth of a drawing.

Two Studies of Legs, about 1526–27, Andrea del Sarto. Red chalk, 14 3/4 × 8 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.73

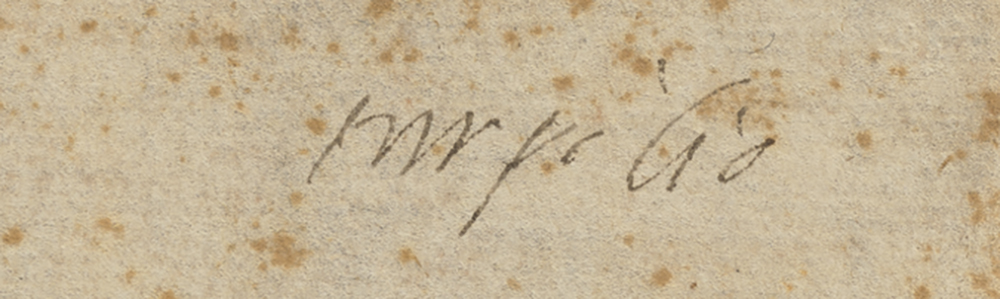

The reverse (back of) the Saint Joseph sheet shows two studies of legs with a mysterious inscription at the top left that seems to read “turpilio.” This is not a typical Italian name, and no one knows what it refers to, though experts think it is probably the name of a person. Also confusing is the fact that the inscription is written in ink, a medium different from the rest of the drawing. This indicates that it was added after the drawing was completed, and yet before Vasari added his border.

Detail through a magnifying glass of the mysterious inscription at the top left of Andrea del Sarto’s Two Studies of Legs. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.73

The inscription on Two Studies of Legs is written upside down. Here, flipped right-side up, you can make out the mysterious word “turpilio.” The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.73

To make things even more mysterious, the word “turpilio” is found scribbled on other drawings by Andrea del Sarto, about 20 of them across multiple international museum collections.

For now, “turpilio” remains a mystery. Perhaps a future scholar, examining a different collection or archive, will be able to uncover its meaning.

A Mysterious Subject

One masterpiece in the exhibition is Titian’s Pastoral Scene, which presents a mystery because of its obscure subject matter. A burning city occupies the background, while the foreground features a boar, a goat, a herd of sheep, a woman covering her face in fabric, and additional figures under a tree. Titian’s work often contains complex iconography, but this one is particularly puzzling.

Pastoral Scene, about 1565, Titian (Tiziano Vecellio). Pen and brown ink, black chalk, heightened with white gouache, 7 11/16 × 11 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.GG.98. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Typically, paintings by old masters like Titian have accompanying documentation, contractual agreements, and many centuries’ worth of art historical research that can help determine the meaning of a work. However, despite the efforts of many scholars, the iconography of this drawing—which lacks extensive archival clues—remains unclear. It doesn’t correlate clearly to any known allegory, to any art historical reference, or even to any of his finished paintings. “There are a lot of theories,” Julian tells me; perhaps one day, someone will figure it out.

A Mysterious Sitter

When you think of European portraits you typically see in an art museum, your mind might conjure images of kings, queens, or other notables. But, sometimes, the subject of a portrait is lost to history.

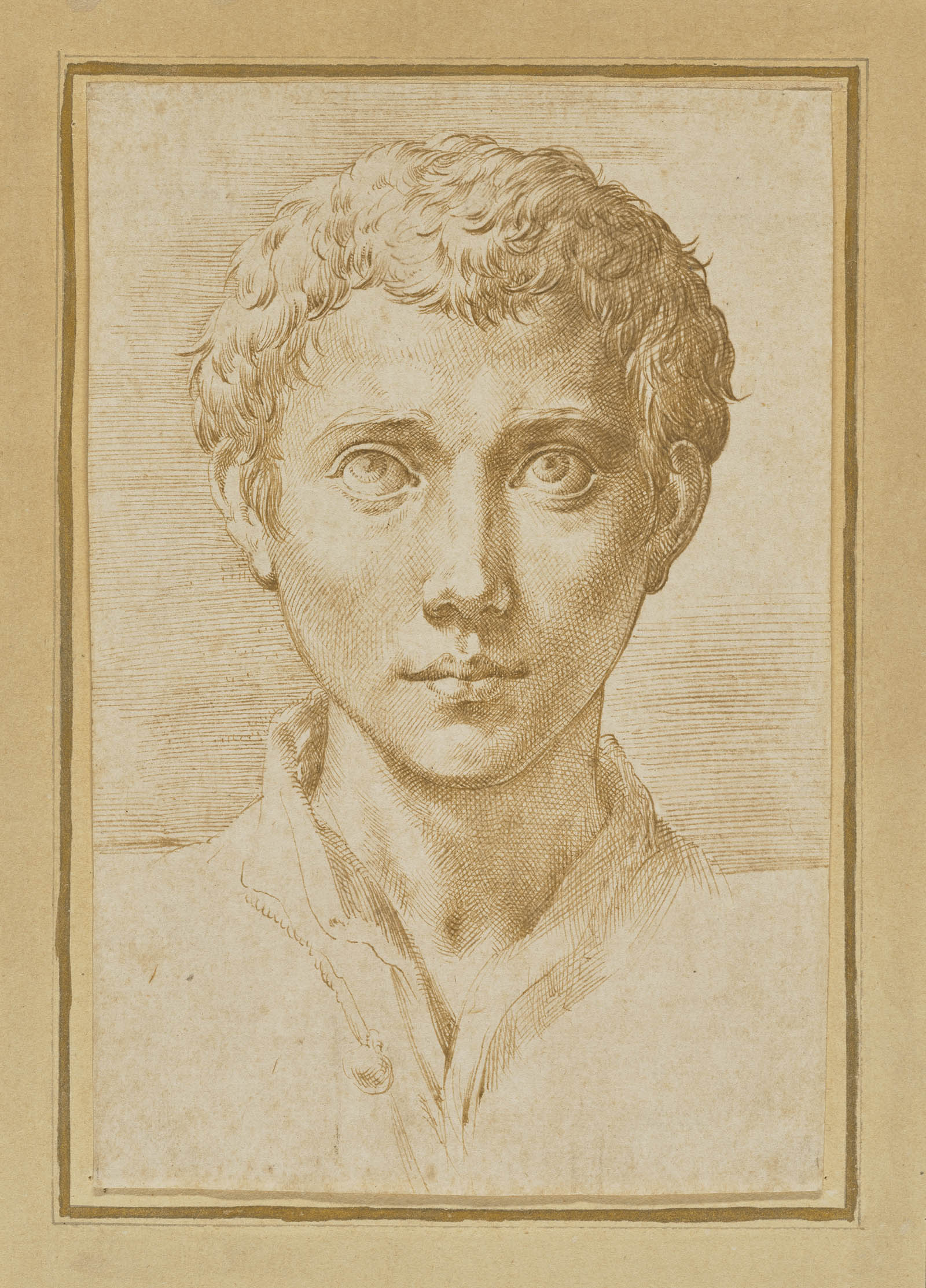

This is the case with Head of a Young Man by Parmigianino. The unique facial characteristics, including the haunting eyes, and the fine detail with which the face is rendered imply that the artist was drawing someone specific. But who? The portrait is not directly preparatory to any known painting by the artist. The fine details suggest it is a finished drawing, not a preparatory work, so perhaps the artist drew a workshop assistant or friend and gave him the sheet as a gift? No one knows, so the sitter remains anonymous.

The Head of a Young Man, about 1539–40, Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola). Pen and brown ink, 6 5/16 × 4 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.79. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Rare Survival

Sometimes it seems like a miracle that any drawings from the Renaissance have survived at all. There are multiple reasons why a drawing wouldn’t last 500 years: they could be victims of fire or flood, or could simply be thrown away.

In his day, Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo was a well-known and prolific painter, but today only 17 of his drawings are known to survive, among them Saint Paul. No one is certain where the remainder of his drawings are or how they were lost, but we’re lucky that this exquisite piece remains. “In the end, it’s just a piece of paper. It’s incredibly fragile. The fact that anything survives is amazing,” says curator Julian Brooks.

Saint Paul, 1533, Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo. Black, white, and red chalk on blue paper; top corners trimmed, 11 3/16 x 8 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 89.GB.54. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The detective work of a curator of old master drawings will always require time, expertise, and painstaking attention to detail. But in the last century and a half, technology has made this art-historical detective work easier. The proliferation of photography and the spread of scholarship through books and the Internet have helped curators further their research and draw new connections. As museums across the globe digitize and publish more and more of their collections, more drawings become accessible all, increasing the chances that an attentive web reader will find new clues to old mysteries.

Comments on this post are now closed.