Festa della porchetta in Bologna, ca. 1716, Angelo Michele Mazza. Etching, 13 ⅗ x 20 ½ in. The Getty Research Institute

Festivals, banquets, and parades were among the few occasions in early modern Europe when entire communities came together. Everyone, from poverty-stricken peasants to grandiose royal families, gathered to celebrate important occasions such as coronations, royal weddings, or victories at war. Extravagant and visually stunning, these events overflowed with food.

The story of European feasting as told in art of the 16th to 18th centuries is the subject of The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals, a new exhibition at the Getty Research Institute. An expanded reprise of a smaller show mounted in 2000, the exhibition displays prints and illustrated books that preserve these ephemeral feasts, and evidence of European food culture, centuries after their inevitable destruction.

The story of European feasting as told in art of the 16th to 18th centuries is the subject of The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals, a new exhibition at the Getty Research Institute. An expanded reprise of a smaller show mounted in 2000, the exhibition displays prints and illustrated books that preserve these ephemeral feasts, and evidence of European food culture, centuries after their inevitable destruction.

The first thing that struck me about the show was its title. What is an “edible monument”? I turned to exhibition curator Marcia Reed, also chief curator at the Getty Research Institute, who revealed that she coined the term herself. An edible monument is simply an artwork or architectural construction that is, in whole or part, made of food. Because such artworks were often meant to be consumed, they have long vanished, and the best evidence we have of them comes from prints and engravings that capture their lost appearance.

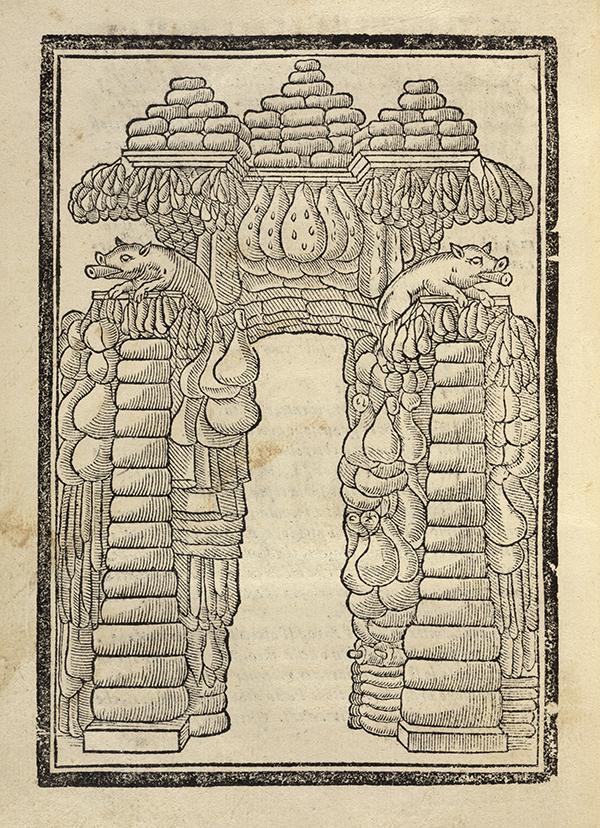

Cuccagna arch of bread, cheese, and suckling pigs, made in honor of Duke Antonio Alvarez di Toledo,

Viceroy of Naples, on the Feast of Saint John the Baptist, 23 June 1629, 1630, Francesco Orilia. Woodcut, 8 ½ x 6 ¼ in. The Getty Research Institute

Edible monuments are made of or covered with food.

This triumphal arch shown above was erected on June 23, 1629, for the Feast of Saint John the Baptist in Naples. It is covered with fruits, vegetables, breads, salami, and roasted pigs, all local products. Some food items on monuments such as these were varnished and painted and hence not actually edible, but most were intended to be consumed during or right after the festival.

Quatrième journée, 1676, Jean Le Pautre. Etching and engraving, 11 ½ x 16 ½ in. The Getty Research Institute

Edible monuments were prominently featured at festivals.

Festivals often began with a procession down a city’s main street. Floats and carriages with royalty on board drove through hungry throngs. Once they reached the palace, the royals joined their noble guests in a sumptuous feast replete with edible art and sumptuous decorative tablescapes.

The scene above shows royal guards blocking courtiers from approaching Louis XIV’s illuminated table sculpture around the fountain at the Marble Court at Versailles, a freestanding outdoor architectural design.

Apparato del convito fatto dall’ill.mo sig senat.e Francesco Ratta all’ill.mo publico, eccelsi signori Anziani, et altra nobilita in numero di 64 nella sala del palazzo gia Vizzani, terminando il confalonierato del primo bimestre dell’anno MDCXCIII, 1693, Giacomo-Maria Giovanni. Etching and engraving, 15 ¾ x 21 ¾ in. The Getty Research Institute

Sugar was often used for edible centerpieces on banquet tables.

The spectacular centerpiece on this circular banquet table is an edible monument, as parts of it are constructed with sugar paste. Smaller sugar sculptures line the perimeter of the table. Such sculptures frequently adorned banquet tables and were typically not intended to be eaten. They were often dyed and gilded and made to be admired as symbols of the host’s wealth, taste, and power—and to be taken away as souvenirs after the feast.

Festa della Porchetta in Bologna, ca. 1735, Giovanni Antonio Belmondo. Etching and engraving, 13 9/10 x 18 9/10 in. The Getty Research Institute

A theatrical stage of edible monuments provided food for some, entertainment for others.

After the feast, the crowd moved outside to the civic plaza. As the upper classes watched from the surrounding buildings and patios, peasants were allowed to run wild and tear away as much food as they could from the edible monuments. Animals would even be let loose in the arena to be hunted down, providing both sport and sustenance.

Title page of Cvccagna: capitolo nel qvale si descriuono le marauigliose cose, che si trouano nel paese di Cuccagna, ca. 1570, Bartolomeo Tosi. Letterpress, woodcut, DIMS TK. The Getty Research Institute

One form of edible monument, the Italian cuccagna, was named after a food utopia.

The word cuccagna may be related to the name “Cockaigne,” a paradise on earth where no one ever goes hungry, grows old, or has to work hard. Here rocks are made of melted cheese and trees of butter. Houses are lined with cheese tarts and have doors made of cakes. Rivers and lakes are made of wine, milk, and honey, and the heavens rain candies.

The fantasy Land of Cockaigne was known throughout Europe, with entire booklets published to describe it. A newly acquired color engraving, complete with lively inscriptions noting every edible point of interest, is included in The Edible Monument.

La cuccagna, e tempio illuminato, ca. 1771, Giulio Cesare Bianchi. Etching, 11 ¼ x 15 ⅘ in. The Getty Research Institute

Tree-shaped cuccagnas were a specialty at Italian festivals.

Cuccagna trees were long greased poles with fruits, game, and poultry hanging from the top. Almost like a circus performance, the peasants struggled to climb up the poles or catch the animals running wild as the nobles observed, cheering them on from their seats.

Cuccagna posta sulla piazza del real palazzo, 1749, Vincenzo dal Re. Etching, 19 ¼ x 28 ¼ in. The Getty Research Institute

A cuccagna could also refer to decorative ephemeral constructions: an entire building, or even a mountain made of food.

Several edible monuments surround the two long poles in the image above. A large fountain of wine sits between the poles, the rails on the staircases are decorated with meats, fowl, cheeses, and breads, and animals roam peacefully on the hill.

How do we know this isn’t the “real” Land of Cockaigne? A group of street beggars running wildly toward the garden from all sides.

_______

#ArtofFood is a series about food in art in medieval, Renaissance, and early modern Europe. It complements the exhibitions The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals at the Getty Research Institute and Eat, Drink, and Be Merry: Food in the Middle Ages and Renaissance at the Getty Museum. Visit the Getty Center to explore both exhibitions via the Art of Food mobile tour.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks