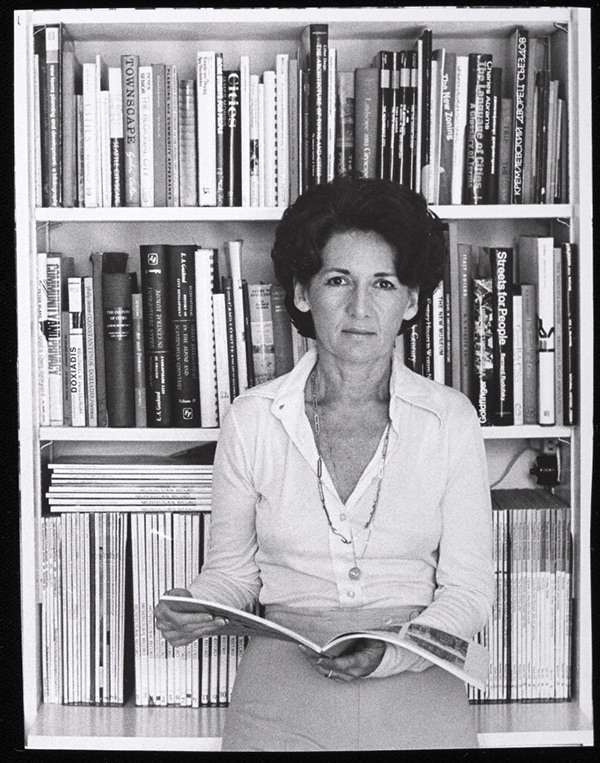

Portrait of Ada Louise Huxtable, 1970s. Photograph by L. Garth Huxtable. The Getty Research Institute, 2013.M.9

When reflecting on her lifetime of research, writing, and academic achievement in the field of architecture, critic Ada Louise Huxtable remarked that “buildings have to stand up.” This statement captures Huxtable’s penchant for recognizing the different ways that architecture directly relates to human beings as social, cultural, and political creatures.

For Huxtable, architecture was a place where design facilitated life. She approached architecture criticism from a holistic point of view, not solely considering a building’s formal and aesthetic features, but also examining the social relations and material conditions of its particular context. Huxtable’s writing frequently delved into the impact a building had in the urban landscape, its ecological factors, zoning, and the social dynamics and historical implications of its place making.

Ada Louise Huxtable honed her wit and enthusiasm for writing as a lifelong New Yorker. She spent her childhood in a Beaux-Arts apartment building and from a young age had a keen interest in observing first-hand the changing architectural landscape of New York City. She studied at Hunter College and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, worked at the Museum of Modern Art, and became the New York Times‘s dedicated architecture critic in 1963.

Huxtable’s Archive

The Ada Louise Huxtable Archive, acquired by the Research Institute in 2013, covers 66 years of her writings and career. The Huxtable papers illuminate the forthright and often acerbic style of writing that Huxtable employed in advancing public awareness of architecture and its civic impact.

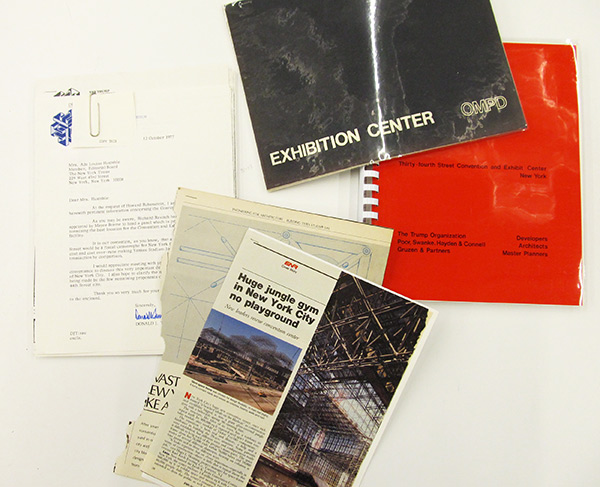

The papers also highlight Huxtable’s complex relationship with architects. Correspondence in the collection shows that architects would regularly appeal to Huxtable’s good favor by sending her original photographs and architectural plans for her own research, as well as personal invitations to their studios. The papers also present letters from architects who responded to a disapproving review with dismay or defense. However, even the architects who considered their work harshly criticized often maintained long-term relationships with Huxtable through correspondence. The New Yorker noted that at a 1973 Architectural League of New York dinner honoring Huxtable, the most notable tribute of the night was the attendance of such architects who had been previously scathed by the critic.

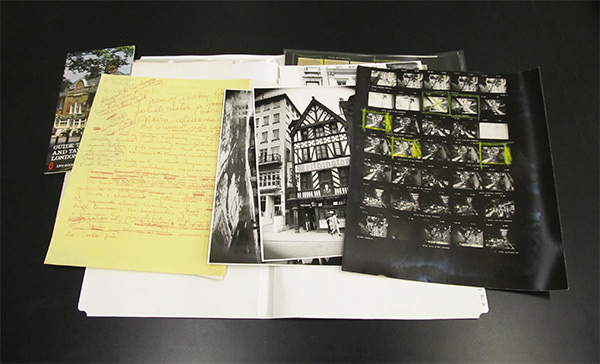

Research file from the Ada Louise Huxtable papers. The Getty Research Institute, 2013.M.9

The archive provides an expansive record of Huxtable’s writing with drafts, typescripts, and printer’s proofs revealing a commitment to the research, writing, and editing process. In addition to her writing on building projects and architecture, the files demonstrate that Huxtable was a capable reviewer of books, art exhibitions, and interior design. The papers also house Huxtable’s ample research files. Contained in the archive are architect files as well as subject files focusing on New York City, planning, urbanism, and preservation. The research files provide a comprehensive account of the shifting movements and concerns in architecture and development over the past fifty years in the US context and internationally.

As evidenced by her research files, Huxtable consistently focused on building preservation as a primary point of concern. She notably lamented the loss of the original Penn Station in New York, drew public awareness to endangered buildings, and specifically advocated to save the historical, social, and cultural integrity of buildings including the New York Manufacturers Trust building, Connecticut’s New London Railroad Station, and the Buffalo State Hospital.

Huxtable’s vocal advocacy against the destruction or severe alteration of landmark buildings led to the founding of the New York City Landmarks Commission in 1965. However, her advocacy did not simply idealize the past, as she refused to support the preservation of structures that merely perpetuated the “stagnant status quo.” Instead, she advocated for stewardship of buildings that served a neighborhood’s aesthetic and civic vitality. In fact, Huxtable’s writings continue to be used by the commission in making decisions about landmark status in New York City.

Inevitably, almost everyone who described Huxtable and her work contrasted her hard-nosed, direct tone of writing with her “birdlike” physicality or “feminine fragility.” Huxtable was less inclined to see herself or the world through the lens of the feminine or gendered. She once said: “I do not think of this in terms of men and women or men [versus] women—I respect people—for integrity and achievement, kindness and wisdom. And to use an old phrase, I do not suffer fools gladly, of either sex.”

Indeed, Huxtable achieved a great deal in the fields of architecture, construction, and city politics—fields historically dominated by men. She was the first woman and only person to be a full-time critic dedicated to covering architecture, first woman to receive the Pulitzer in criticism, only the second woman to join the New York Times editorial board. And such trailblazing was not unrecognized as she received letters from other women inspired by her accomplishments as well as receiving several women’s division awards. Huxtable rather measured her achievement in the context of her ability to affect change.

Access the newly completed finding aid for the Ada Louise Huxtable papers here.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.