Ancient works of art illustrate that music had a strong presence in daily life of classical Greece and Rome. Vase paintings and sculptures in the antiquities collection offer an eye-opening view of the variety of musical instruments that were played, as well as the contexts in which they were performed.

Sarcophagus with Scenes of Bacchus (detail of a maenad, a female follower of Dionysos, playing the tympanum), Roman, A.D. 210–220. Marble, 67 15/16 in. wide. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.AA.275

By looking closely at works of art, we know that music played a role in rituals associated with Dionysos, the Greek god of theater and wine. Music, like wine, was perceived to have transformative qualities, transporting one’s consciousness from a state of awareness to ecstasis. The front panel of this Roman sarcophagus shows a Dionysiac revel, in which a symphony of instruments—from the aulos to the tympanum, the lyre to the kymbala—is played by maenads and satyrs alike.

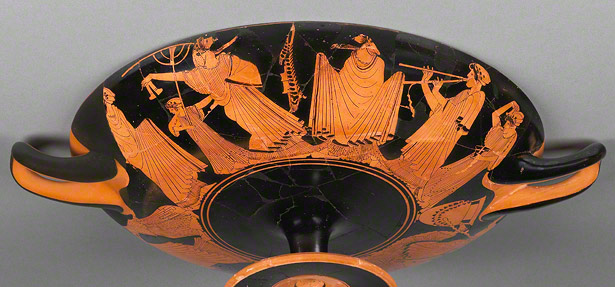

Like today, music also played an important role at parties. One of the primary sources for understanding ancient music is artifacts used in and depicting the symposion (symposium), a male drinking party reserved for the aristocrats of Greek society. This drinking cup illustrates several musicians in action. Entertainers play the krotala and the aulos while dancers move to their rhythms.

Ancient musicians in action. Wine Cup with Flirtation Scene (inverted view of exterior, with detail below), attributed to the Briseis Painter, vase-painter, and Brygos, potter. Greek, made in Athens, about 480–470 B.C. Terracotta, 12 1/16 in. diam. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 86.AE.293

While few actual instruments or musical notations survive, iconography on works of art informs us quite a bit about possible performance techniques, the timbre of an instrument, how instruments were made, and the ways ancient instruments connect to modern-day ones.

At the Getty Villa, we took this idea a step further by inviting the contemporary musical duo Musicàntica for a series of artist-at-work demonstrations in February and May 2012. Art might provide a lot of information, but images of music really need a soundtrack.

Enzo Fina and Roberto Catalano, who make up Musicàntica, explore the oral traditions of the Italian outlier: the music of the southern Italian peasantry, fishermen, and street vendors whose musical history is passed from generation to generation by untrained players. While thousands of years separate Musicàntica from their ancient counterparts depicted in works of art at the Villa, their instruments connect them across time. As part of their repertoire, Musicàntica highlights instruments that are directly connected to their ancient roots.

For example, the benas, a single and double Sardinian reed clarinet, has its roots in the aulos, an ancient wind instrument like the modern clarinet and oboe.

The benas, a Sardinian reed clarinet, is the direct descendant of the ancient aulos.

Playing the aulos. Water Jar with a Reveler, attributed to the Eucharides Painter. Greek, made in Athens, about 480 B.C. Terracotta, 15 5/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 86.AE.227

Ancient musicians used the circular breathing technique, a method in which a player inhales from the nose, fills his cheeks with air, and slowly blows it out of the instrument in a circular fashion. The sound was continuous but imposed a great deal of stress on the musician.

To play the benas, Roberto wore a phorbeia, a leather strap used by ancient aulettes (players of the aulos) to compensate for the stress on the cheeks and lips caused by blowing into the instrument.

During the artist-at-work demo at the Villa, Roberto Catalano wears a phorbeia (leather strap) to play the benas, a Sardinian reed clarinet descended from the ancient aulos.

An ancient aulette blows on his instrument (now lost). Head of a Boy Piper, Greek, about 320 B.C. Marble, 9 7/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 73.AA.30

And in this video clip, Enzo Fina demonstrates how he plays the ancient tympanum using its direct modern descendant, the frame drum.

While today’s instruments give us a sense of what their ancient counterparts might have sounded like, reconstructions can be just as informative. In the video below, Roberto Catalano improvises on a replica chelys lyre, tuned in the Dorian mode. The name derives from the Greek word for the shell of a tortoise, chelys, which functioned as the sound box. According to Greek myth, the first lyre was made by the god Hermes from a tortoise shell, as well as the horns and hide of an ox stolen from his brother, Apollo. This lyre has a sounding box made from the shell of the European tortoise, once plentiful in Europe, and wooden arms.

These examples show that ancient music has not fallen silent!

To explore ancient music further, here are two of my favorite sources: sounds of ancient papyri with evidence of musical notations, sound bites, and a bibliography, and reconstructed ancient instruments and more sound examples.

It’s amazing how musical instruments have developed over time – I wonder how instruments will evolve over the next 100 years…

they probably won’t change any in the next 100 years.

How do we begin to understand or interpret any ancient musical notations? At uni a teacher played our class what he felt was an approximation of music from ancient Greece, but didn’t explain how he had learnt to intepret the notation used. Always been curious about that.

http://bit.ly/1IZPmwl

Thanks to a treatise with musical tables from late antiquity (5 cent AD) by Alypius, with a continuous manuscript tradition through to the Renaissance and today, scholars have always in principle been able to read the notation of ancient music as preserved on stone and papyrus. Ancient Greeks were mathematically precise about musical intervals and such theorists as Ptolemy give very detailed descriptions of modes and the notes used in them. If only more notated music could be found! If you want to know more, the best current compilation is that of Pöhlmann, E, and West, M.L. Documents of Ancient Greek Music, Oxford 2001. A very good description of the notation, with tables, is available in West, M.L., Ancient Greek Music (Oxford 1992).