Goats stand in front of the Frankish monastery of Isova in Greece. Photo: Hercules Milas / Alamy

“According to local lore, this wall was built by shepherds to provide a windbreak for their flocks.”

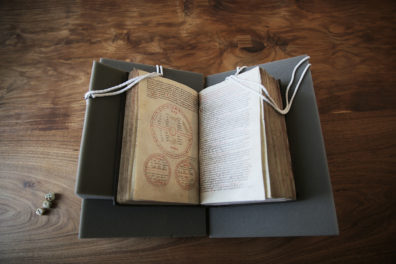

We had just arrived at the Greek site of the long-ruined church of the Isova Monastery. Our group had come to see its pointed-arch windows—a characteristic of Gothic architecture and clear evidence that the Crusaders had imported French style after invading and claiming this former corner of the Byzantine Empire. But what was holding our attention was an unprepossessing length of masonry that cuts across the nave of the grand old church.

In the foreground is the masonry wall inside the Isova Monastery. The far wall includes pointed-arch window frames. Photo: Elizabeth Mansfield

Scholar Michalis Olympios was giving an introduction to the monastery to his fellow participants in the Art of the Crusades program, a series of research seminars supported by the Getty Foundation as part of its Connecting Art Histories initiative. Olympios’s expertise in the adaptation of Gothic architecture in the Eastern Mediterranean was well known by the group after their earlier study of similar sites in Turkey and Israel, so they listened attentively to his account. Even the part about the shepherds.

Modern Rome – Campo Vaccino, 1839, Joseph Mallord William Turner. Oil on canvas, 36 1/8 × 48 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.6

As a program officer at the Getty Foundation, I was accompanying the group as an observer. My background as a scholar of 18th– and 19th-century European painting made the “shepherds among the ruins” theory seem reasonable. After all, the long-abandoned site looked very much like the pastoral setting depicted in thousands of European landscape paintings that feature rustics among ancient ruins.

But the program participants were not so gullible. These were senior and emerging scholars of Islamic, Byzantine, and Gothic art and archaeology. They recorded Olympios’s observation in their notebooks, but skepticism furrowed their brows and played at the corners of their mouths. Olympios paused and smiled. After a shared laugh, everyone closed in for a closer look at the anomalous structure.

The Importance of Material Culture to Crusader-Era Scholarship

The gathered group of scholars understood that clues to the origins of this monastery, the religious beliefs of its congregation, and the political ambitions of its founders were more likely to be found in the chinks of irregular masonry and carefully dressed stone window frames than in any archive.

Few written records remain from the French knights who came to the Peloponnese region of Greece in the 13th century as Catholic pilgrim-invaders. Frankish rule of this area, called the Principality of the Morea, lasted roughly two centuries, from the 13th to the 15th century. By 1432, most of the Peloponnese had been restored to the Byzantine Empire; in 1460, the territory became part of the Ottoman Empire. Neither Byzantine followers of the Orthodox Church nor the Ottoman Muslims would have had much use for legal or religious documents created during Frankish rule, so their loss is not surprising. The most important extant source on the Frankish kingdom is the 14th-century Chronicle of the Morea, a 9,000-line account in verse that is as rich in literary embellishment as it is in historical fact.

The paucity of archival documents makes the archaeological and artistic record of the era even more important. Evidence of Frankish settlement—from its most violent to its most benign incarnations—is abundant across the region. Distinctively French donjons with imposing towers and fortification walls still keep a ghostly watch from strategic heights, and Gothic flourishes adorn dozens of Byzantine churches, many of which remain in use today. Aesthetic affinity as well as practical necessity preserved many Frankish structures from destruction or grave defacement; however, in some cases, Frankish monuments were demolished as soon as the region was retaken. This was the fate of Isova, which was burned.

Why some buildings survived the cultural upheavals of the Middle Ages while others did not is just one of the questions faced by those participating in the Art of the Crusades seminars. In an unprecedented collaboration, these experts have been brought together to inaugurate a multidisciplinary approach to interpreting the material culture of the so-called Crusader Era. Whether examining an exquisite piece of painted pottery, a finely carved grave marker, a horde of silver coins, or a humble masonry wall, the group brings the same intellectual energy and curiosity to the visual evidence.

The exchange of ideas prompted by members’ shared encounter with the material culture of the Crusader Era promises to significantly advance the study of medieval art and architecture of the Mediterranean. Proceeding from the assumption that visual forms and aesthetic impulses flow continuously across religious and regional boundaries, they are developing a richer—and more accurate—understanding of the art created by the region’s historic and heterogeneous population of Jews, Muslims, and Christians.

Inspecting the Wall for Clues to Its Maker

Art of Crusades project team members get a closer look at the masonry wall. Photo: Elizabeth Mansfield

Left to right: Gil Fishhof (Tel Aviv University), Edna J. Stern (Israel Antiquities Authority), and Michalis Olympios (University of Cyprus) discuss the construction of the wall in question. Photo: Elizabeth Mansfield

“Well, those shepherds may not have been the most skillful masons but they certainly understood twelfth-century Byzantine building techniques,” observed one member of the group. If the wall was a later addition to the site, it hadn’t been erected too long after the construction of the church’s impressive exterior walls.

But the wall definitely wasn’t built by shepherds. Along with medieval masonry techniques, the wall exhibited a distinctive feature that completely ruled out the wind-chilled shepherd theory. Plainly visible on its eastern side were a series of ceramic forms embedded in the masonry. They looked like red clay bowls.

Detail of the wall showing an embedded clay vessel. Photo: Elizabeth Mansfield

This was a feature the group had encountered before at other ruined churches in the region. It was, in fact, something that could only be seen where a wall had been damaged. Clay vessels had been sealed within the wall when it was built to serve as hidden resonators. They would have amplified and lent texture to the voice of the priest during the singing of the liturgy. The existence of this well-documented feature of medieval church design confirmed that the wall had been part of the original monastery.

But the puzzle was not solved yet. What purpose could the wall have served? Queried one participant: “Do we know whether it was a men’s monastery or a women’s convent?” “The Chronicle of Morea is not specific on this point, but it is certainly possible that it was a convent,” Olympios replied.

Perhaps, then, the wall was built to maintain the necessary separation between the priests and the cloistered nuns? Such dividing walls are a standard feature of convent churches. “No, that’s not possible,” observed another participant as several nodded in agreement. “If that were the case, we would expect the wall to be pierced by openings so the nuns could see the main altar and receive the host.”

Other participants noted that the height of the pots also seemed strangely low. Was the wall then an iconostasis, a screen for the display of icons? Possibly. Such screens, sometimes made of wood but other times of stone, are found in Eastern Orthodox churches and allow the veneration of icons. But this hypothesis also raised some questions.

The Chronicle of the Morea suggests the monastery was built by Franks during the 13th century and then destroyed soon after by mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine army. If so, then the church would have been designed to facilitate the Latin Rite and no iconostasis would have been needed. That is, unless the church had not been destroyed as reported in the Chronicle. Could the church instead have been refitted to accommodate Eastern Orthodox worship? If so, then when was the monastery destroyed? And by whom? And…who built that wall?

To consider this question, the group compared the ruins to sites they had examined together in Israel and Turkey during their first seminar, as well as other sites in Greece. Drawing on their diverse expertise, the scholars formed a hypothesis. The wall was probably not the remains of an iconostasis, and varying qualities of craftsmanship could simply be evidence of a diverse labor pool instead of proof of a later phase of construction. Most likely, the monastery was built by local laborers with some guidance from Frankish masons brought to the Peloponnese by French crusaders intent on establishing the authority of the Latin Church, the source of their own claims to power in the region.

A large monastic complex like that of Isova was intended to make an impression. The itinerant Frankish masons provided crucial direction for the design and construction of the load-bearing walls, where Gothic features are most evident. Other parts of the church, according to this hypothesis, were left to the locals to devise, enabling the foreign craftsmen to move on to other projects.

The only way to confirm this hypothesis would be through careful excavation of the entire site. For now, though, the best way to test it is through close study of comparable Frankish structures in the region. Prompted to resume their trek by the lengthening afternoon shadows, the scholars brought together by the Art of the Crusades took a few final photographs of the monastery and boarded the bus, continuing onward to track the course of the medieval craftsmen who had brought this beguiling mix of Byzantine, Frankish, and Islamic art and architecture to the region.

Comments on this post are now closed.