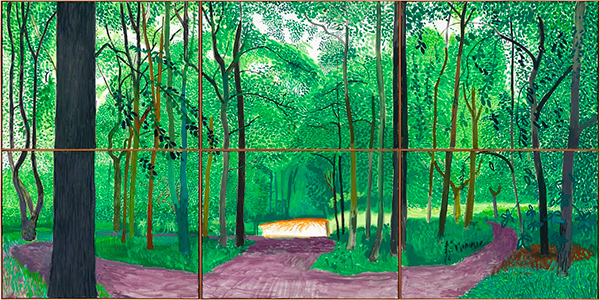

From the de Young exhibition: Woldgate Woods, 26, 27 & 30 July 2006, 2006, David Hockney. Oil on six canvases (36 x 48 in. each), 72 x 144 in. overall. Artwork © David Hockney. Photo: Richard Schmidt

“There’s too much green here,” my friend said as we entered a gallery at the de Young Museum last month. I had flown up to San Francisco to see an exhibition of David Hockney’s work from the last decade—oil, acrylic, and watercolor paintings, iPad and computer “drawings,” and video pieces.

That gallery in the de Young’s David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition was filled with English landscape paintings. Almost every canvas included a passage of bright green. My friend, who is a painter herself, noted that it’s a tough color to use. It can dominate a painting—and it dominated that gallery.

As an art historian, I’ve been looking at Hockney’s work for nearly 30 years. Standing in that gallery, I wondered: Why is vibrant color, like green, characteristic of Hockney’s landscapes of Northern England?

I think it has to do with the nearly 30 years that he lived in L.A.

Yorkshire, where Hockney was born and raised, can be predominantly grey in certain seasons. I think those vibrant greens took root in L.A. and blossomed even more brightly on his return to England. It seems the lack of color there at some times of the year made the presence of color at other times dramatic in ways he hadn’t realized before.

Hockney brought with him to L.A. a solid British art education. He attended the Bradford School of Art in Yorkshire, and then the Royal College of Art in London, where he studied with Francis Bacon, among other visiting artists and faculty. He also regularly attended art exhibitions. London in the early ’60s gave him a taste of the international art scene.

Shortly after graduation, he began traveling the world. He visited New York City in 1961, and two years later, London’s Sunday Times commissioned him to make drawings in Egypt. Travel clearly stimulated his picture making. It also enlarged his worldview and made his reputation as an international artist.

In 1964, he made his first visit to L.A. and was fascinated by the idiosyncrasies of life here. That year, on February 11, he mailed a postcard from Santa Monica to his London dealer John Kasmin, proclaiming the temperature was 76 and that he had found “the world’s most beautiful city”… a “promised land.”

In his 1967 painting Lawn Being Sprinkled, Hockney marvels at the sort of everyday scene to which Angelenos are accustomed. In Hockney’s painting, the v-shaped mists of water create a pattern over the very green grass while a clear blue sky caps the view. The composition is a generalization—an abstraction almost—of the way we live here. The strangeness of this dry, desert paradise with its bright lawns and cultivated gardens and open lifestyle became a primary source of inspiration for his art-making.

An L.A. Hockney in L.A.: Pearblossom Hwy., 11–18th April 1986, #2, 1986, David Hockney. Chromogenic prints mounted on paper honeycomb panel, 78 x 111 in. In the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Artwork © 1986 David Hockney

Hockney made Los Angeles his permanent home in 1978. He lived here until 2005, when he returned to his native Yorkshire. But as of 2013, he has moved back to L.A. again. It will be interesting to see what lessons he brought back with him.

His return to California is a triumphant one; he has become a kind of modern old master. He’s an old master not only because this year he’ll turn 77, but also in the sense that art historians use that term as a kind of honorific. He’s a master painter who was trained in the solidly academic British tradition and who has learned from looking closely at work by historic artists ranging from Vermeer to Picasso. And finally, he’s an inveterate experimenter who constantly seeks to understand and master technologies both old and new that can be used for the making of art.

After seeing the de Young exhibition, I wanted to compare his work made in L.A. to that done away from here. So I visited Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), where one of his masterpieces is on permanent view.

Mulholland Drive, The Road to the Studio, 1980, David Hockney. Acrylic on canvas, 86 x 243 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by the F. Patrick Burns Request. © David Hockney. All rights reserved

Mulholland Drive, The Road to the Studio (1980) is pure L.A., a celebration of light, color, topography, and man’s imprint on the natural environment. This billboard-sized painting of an undulating road follows Hockney’s daily drive from his home in the Hollywood Hills to his studio on Santa Monica Boulevard. Shifting perspectives take the viewer in and out of the curving road and up and down the hillside. The painting depicts what Hockney saw on this familiar drive—tennis courts, a swimming pool, cypress and palm trees, and the grid layout of the Valley. It’s both a map and a huge landscape whose multiple perspectives reveal the crazy-quilt mix that makes this place unique.

Mulholland Drive is also a riot of saturated SoCal colors—blue, green, orange, red, purple. It shows his full repertoire of “mark making,” or applications of paint to a canvas: a quick dash, a long sweeping line, a dot, a scrape. Hockney used numerous techniques and created different textures to describe the topography and features.

While at LACMA, I also spent time with Hockney’s installation of Seven Yorkshire Landscape Videos (2011). The fixed perspective he uses for the English multi-screen videos offer a stable, “bigger” picture of the flat expanse of his native countryside. There’s no up and down and curving around here. The roads are straight and narrow, and the near and far are seen from one vantage point.

Painting different seasons, he finds different light effects, creates open vistas with breathing space, and fixes a perspective to show an underlying structure. Hockney seems infatuated with spring and summer—when the greens are greener and in abundance. Those are the seasons of growth, new life, and the cycle starting over again.

For Angelenos who don’t have time for a trip to San Francisco to see the exhibition at the de Young Museum before it closes January 20, I recommend a visit to LACMA. It’s worthwhile to compare Hockney’s L.A. painting of Mulholland Drive with the multi-screen video of Northern England. One is a roller-coaster ride, and the other is an intimate view from a single perch. One is derived from the thrill of a new experience, while the other is embedded in memory that’s newly stimulated.

Text of this post © Zócalo Public Square. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.